pril 13, 2025, is the 50th anniversary of the formal start of the Lebanese Civil War. That day, Palestinian gunmen shot up civilians coming out of a Maronite church in Beirut while later that same day Lebanese Maronite gunmen shot up a bus carrying Palestinian civilians coming from a Palestinian militant rally.[1] The first Lebanese “martyr” of that war was Maronite Joseph Abu Assi, cut down outside that church after witnessing his son’s baptism.

While both events happened the same day and hours apart, expect most commentators to dwell, as they did back in 1975, on the infamous Black Sunday “bus massacre” while making scant mention of the drive-by shooting on the church.

The war would rage, on and off, for 15 long years, drag in neighboring and global powers, turbocharge terrorism, and devastate a tiny country. While retrospectives may seek to assign blame here or there, in my view one of the main instigators of the Lebanese Civil War was already dead when it happened. That would have been Egyptian dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser.

It is the November 1969 Cairo Agreement which fatefully set the stage for the Civil War.[2]That agreement, in the shadow of the Arab defeat at the hands of Israel in 1967, legitimized the presence, and military independence, of Palestinian armed factions in Lebanon, creating a Palestinian state within a state which would provoke Israel and disastrously interfere militarily in Lebanese affairs and which would serve as a pattern for future intervention in Lebanon by foreign powers which continues to this day.

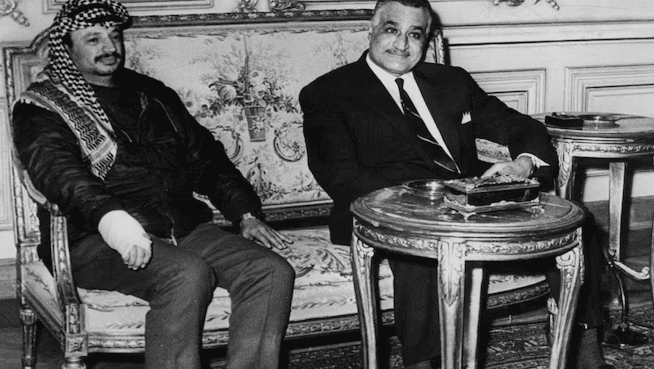

While the Lebanese were pressured into an agreement by Nasser, working closely with PLO leader Yasser Arafat, the Lebanese walked openly into the accord, which was initialed by Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) commander General Emile Boustany. Much of the Lebanese political elite, even the Maronite elite, endorsed the agreement. Christian leaders like Pierre Gemayel and Camille Chamoun did so with the proviso that the agreement would be strictly endorsed, which it never was. A main motivation for the agreement by the Lebanese was to try to keep the already fracturing country together. The Maronite president at the time had expressed concern about Palestinian attacks on Israel from Lebanese soil while the country’s Sunni Muslim prime minister had openly disagreed with his own president.

Regardless of the motivations and the details of the agreement, it was a deadly step. Journalist Edouard Saab, who would be killed by a sniper during the war in 1976, wrote in 1969 of the agreement: “Why do they want what is not permitted in Syria, to be allowed in Lebanon?” And so, it would be. Cross-border raids and direct attacks on Israel that Nasser in Egypt and Assad in Syria and, after September 1970, Hussein in Jordan would not allow would be accepted in Lebanon. And not only that but Beirut would become the headquarters of Palestinian factions funded by outside regimes – from Syria, Iraq, and Libya. Eventually, the Lebanese capital, the capital city of a foreign country, would be dubbed by the PLO as first the “Hanoi” and then the “Stalingrad of the Arabs.”[3]

By 1975, armed Palestinian factions would become an equalizer in the just-exploded civil war, as Lebanese Christian militias fought mostly Muslim/leftist Lebanese militias and Palestinian factions. During the early years of the war, it seemed that the pro-Palestinian Lebanese militias were actually the junior partner in the struggle. The PLO was dominant on the anti-Lebanese Christian side from 1975 to 1982. After that and the 1982 Israeli invasion and evacuation of PLO fighters in September of that year, the war would be between Lebanese factions dominated by Syria against Lebanese Christian factions supported by Israel, and later by Iraq, until the war’s end in 1990.

What would the war have been like without the active military participation of the PLO? Would it even have occurred? Perhaps the Christian armed factions would have won. But more likely, the crisis would still have led to war and the war would perhaps have ended sooner in some sort of stalemate or internal compromise like the 1958 Lebanese Crisis.

That earlier war had had a similar internal lineup – but without the destabilizing presence of Palestinian fighters – and included direct American intervention. The 1958 crisis was – aside from the internal political dimension – also an attempt by Nasser (who then ruled in both Syria and Egypt) to project power in Lebanon. The American intervention was brief and the Lebanese were able to, among themselves, work out a political agreement which bought the country a generation of – if not real stability – no war from 1958 to 1975.

Despite increasing misgivings about the 1969 Cairo Agreement, it was only repudiated by Lebanon in 1987 under President Amin Gemayel and yet the legacy of the agreement remains. Lebanon is still to be considered an anti-Israel free fire zone as it had been under the PLO. Other Arab borders with Israel would remain relatively quiet but Lebanon would remain an active shooting gallery, first by PLO factions, then by Lebanese factions supported by Syria and Iran (particularly Hezbollah).

Today Palestinian factions, chiefly Hamas, still fire rockets into Israel, are still armed and still have their arsenals and enclaves where the Lebanese Army dare not go, cowed if not by the Palestinians, by the Palestinians’ great protector in Lebanon, Hezbollah. The ghost of General Emile Boustany lived on in General, and especially President, Michel Aoun (and other local politicians) who would legitimize eternal war by factions outside the state waged on Lebanon’s border in return for fleeting, short-term political gains.

I am sure that there will be great and thoughtful introspection by the Lebanese, a cultured and intelligent people, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Civil War. Some will blame themselves and some will blame foreigners, or a combination of both. Incredibly, after Hezbollah’s recent defeat in the Gaza War at the hands of Israel, Lebanese political leaders still seem ambivalent about finally exiting from the trap first fashioned by Nasser and the 1969 Cairo Agreement.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice President of MEMRI.