U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital has returned the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to the headlines. The move reversed half-a-century of U.S. policy and dismissed a U.N. consensus to remain neutral on Jerusalem’s status until a final peace deal.

Many diplomats and observers warn that the move may have finally put an end to any prospect of a two-state solution in the Holy Land. Palestinian lawyer and writer Raja Shehadeh has, however, long been pessimistic about any such solution, witnessing first-hand how official policy has for decades undermined any potential grounds for a viable two-state agreement.

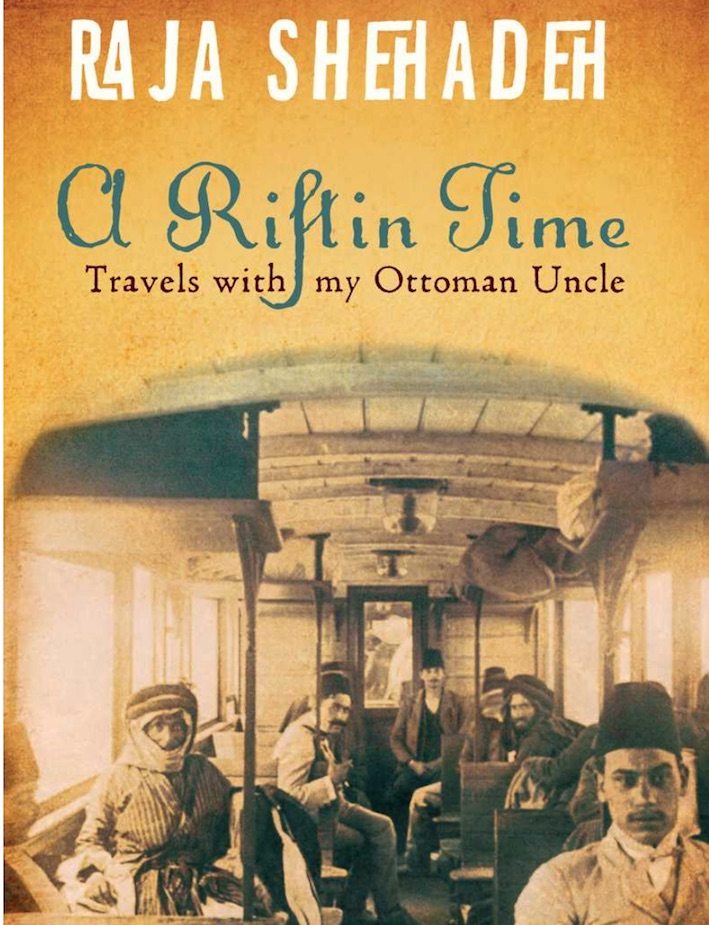

Along with his work at the Ramallah-based human rights association Al-Haq, Shehadeh has written eight books so far examining the history of Palestine and the human cost of the Israeli occupation. Among the most eloquent is “A Rift in Time: Travels with my Ottoman Uncle” (reviewed in HDN here), in which he traces the path of his great uncle Najib Nassar, who spent three years on the run from the Ottoman authorities in Greater Syria during the First World War.

Shehadeh spoke to the Hürriyet Daily News about the life of Najib and the experience of following in his footsteps 100 years later.

Let’s start by introducing Najib Nassar. Who was he? What did he do? Describe the context of his life?

Najib Nassar originally came from Lebanon. His family came to Palestine in the last part of the 19th century. His brother worked as a medical doctor at the Scottish hospice in Tiberius and Najib also came. They settled in Haifa, where one of his brothers was a hotelier. In 1908, when censorship was removed in the Ottoman Empire [with the Young Turk Revolution]Najib decided to establish a biweekly newspaper called Al-Karmil. He was a campaigning journalist. In Al-Karmil he was concerned with the encroachment of Zionists and the increasing of land and settlements in Palestine, near where he lived. In 1908 Najib wrote the first book in Arabic about Zionism and its dangers. He warned about the dangers of what would befall Palestine if Zionism succeeded. He also wrote novels and he was very concerned about agriculture because there is a water problem in Palestine, so he translated a book on dry agriculture.

Then in 1915 apparently the Ottoman and German authorities tried to recruit him to the cause of the First World War. But in his view it was wrong for the Ottoman Empire to join the war, and if it was going to join it was wrong to do so on the side of the Germans because he thought that the British, who had a very strong fleet, could impose a sea blockade, which would mean that the country was starved. He was approached by the Germans several times to use his newspaper as a propaganda instrument for the war but he refused. They took this as meaning that he was on the side of the British.

At the time the Ottoman Empire was very insecure and many Arab leaders were being rounded up and hanged. Najib received an arrest warrant in 1915. At first he didn’t take it seriously because he thought he had strong relations with the Ottoman establishment. But he soon realized that it was serious. If he was arrested they would very likely put him on trial, find him guilty and execute him. So he went on the run for three years after 1915. That is what I write about.

How did your family view Najib’s life?

He wasn’t spoken about very much in my family. My grandmother’s father was Najib’s uncle. Every once in a while, after the 1948 Nakba, she said things like “Najib was right, we should have listened to him.” I never quite understood what she was talking about. She also said Najib once came to visit and was in such an appalling state – dirty with a big beard – that they thought he was a beggar. But then they took him in and realized he’d been on the run. This intrigued me. Who was this Najib? So I started reading.

What sources did you use to research his life?

I was lucky to find an account of his three years on the run, which he called a novel but which was in fact autobiographical. It was full of details about what he saw, who he met and how he felt while he was on the run. Al-Karmil, the newspaper he edited, was another important source. Also from 1920 to 1924 Najib traveled around Palestine and wrote what he called “letters” from various parts of the country, describing the situation he found there.

Najib believed in greater autonomy for the Arab majority parts of the empire but within the Ottoman system. At a time during the war when Cemal Pasha, the notorious governor of Syria, was overseeing a kind of tyranny where many Arab nationalists were being jailed or hung, Najib clung onto an idea of the Ottoman Empire as an ideal overarching structure.

He had actually given up on the Ottoman Empire before the constitution of 1908 and was thinking of emigrating to the United States, like many others of his class at the time. But when the constitution was implemented it gave some freedom and made some important changes in the life of the place. So Najib’s confidence revived and he became excited about the possibility of a good life under the Ottomans.

The thing I came to understand through working on the book is that the consciousness of people at that time was of a continuous place: Greater Syria. This is so unlike the present, where the area is fragmented into many different countries, borders, and borders within borders. When Najib was on the run and had to travel across the Jordan River to the East Bank in what is now Jordan, he went on horseback. He had no feeling that he was crossing borders because he wasn’t actually crossing borders, it was all one country. The political place and political reality was so unlike today, which has been ruined by various small nationalisms and imperialists who divided the area and made it into many little countries that aren’t viable on their own. All the Arab countries in the region, as well as Israel, depend massively on support and money from outside.

The case of Najib is doubly interesting because he was an Arab Christian.

The Ottoman Empire was a multi-ethnic empire with a place for everyone. The fact that Najib was a Christian made him no less Ottoman than a Muslim. He didn’t feel that he was being discriminated against because he was Christian. Of course during the First World War everything changed and Arabs started to be discriminated against. At first Christians were exempt from serving in the army but later on everyone had to serve in the army unless they paid a lot of money. But before the war the Ottoman Empire was multi-ethnic and it worked for 450 years.

Najib had some extraordinary experiences while he was on the run.

It’s quite amazing how much support he was getting. Because at that time if you took into your home someone who was on the run you ran the risk of being executed. It was not a joke. Najib always found refuge in homes and with tribes, who took great risks in sheltering him. He had good relations with Bedouin tribes and people across the region, who he had supported in his newspaper and in his generosity as a farmer. At first he wasn’t quite sure how dangerous it was and he had a number of very close runs.

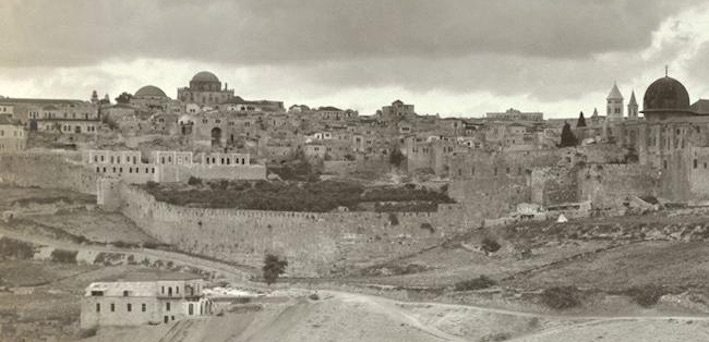

He went around from place to place. I tried to follow the route he took but it was far from easy. Most of the places he talked about in his autobiographical novel have been completely destroyed by the Israelis and replaced by Jewish settlements and towns.

What particularly struck you as you took the same route almost 100 years later.

I learned a lot on the way, much more than I had anticipated. The first problem was to locate the actual route that Najib took. I had to find a map that featured the places he mentioned. All the new maps have been rewritten and only mention the new Israeli places. I found only one map, an Israeli map, that featured the destroyed villages. I had to go to Edinburgh to the National Library of Maps to find other old maps of these places.

Then I had to go to the land itself and imagine how it was. In one case, I looked from a high vantage point and I couldn’t see any sign of the villages Najib mentioned. Elsewhere I saw that there were blooming almond trees in an empty area. Because I myself am a gardener with an interest in agriculture I knew that almond tress don’t just grow on their own, they have to be cultivated. So who had cultivated these trees? It must have been villagers who once lived in the area. So when I looked carefully I saw a kind of matrix of almond trees that indicated villages from Najib’s time. After 1948 they were destroyed.

There was also a view of the land that I realized I had internalized: The new geography that had been imposed on the land as I and other Palestinians now live it. In the Jordan Valley I was going through many checkpoints but I realized that the real thing was the Rift Valley, which stretches all the way from the Taurus Mountains down to Mozambique. The Rift Valley is a physical, geographical place on the earth that cannot be destroyed and is more permanent than any of these areas fragmented by borders or checkpoints. Once I started looking at the land with these new eyes I got a sense of freedom that I never had before. And this was thanks to Najib.

In the book you refer to many resonances between Najib’s situation and your own today.

We were both using our profession to campaign: In his case journalism and in my case the law. We both thought that through campaigning and trying to inform people about what was happening we could make a difference. He was passionate about the importance of farmers staying on the land, while I have also been passionate about the importance of “somud” or staying put – for the Palestinians to stay on the land and not to move away. Because if they move away they will be replaced by Israeli Jews.

But at the same time we both overestimated the importance of our work. In Najib’s case he thought he could stop Zionism and stop land sales. In my case I thought that by informing people about the law and informing people about the changes that Israel was making in the occupied territories, international law would be enforced and could make a difference.

Najib was very concerned about land sales. At the end of 1948 only a small portion of the land had been sold or was in Jewish hands. The rest was in Arab hands. So it wasn’t really the question of land sales that would make a difference; it was really war and violence. The Israeli state was established as a result of a war they fought in which they terrorized the Arabs and forced them out of the country. In my case, showing the various legal ploys that are used to justify the takeover of the land for settlements, and all attempts to dispute these at the Israeli high court, have not really mattered. They have always found another ploy. The legal aspect was always just a facade.

What about the rest of Najib’s life? What did he go on to do in the years following the First World War?

He had a very sad ending. He continued to publish until 1940 but he didn’t have the same enthusiasm and he felt he wasn’t appreciated. He felt he had been advocating things that there wasn’t a strong response to. He saw things declining and so retreated to his farm. He felt very pessimistic and his health also wasn’t very good. Perhaps fortunately for him he died before 1948 and he was buried in Nazareth. So he didn’t have to endure the added insult and tragedy of the Nakba, when the Palestinians were forced out of Palestine. But his last years were sad years; he felt that everything he had worked for had failed.

* Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via iTunes here, Stitcher here, Podbean here, or Facebook here, or Twitter here.