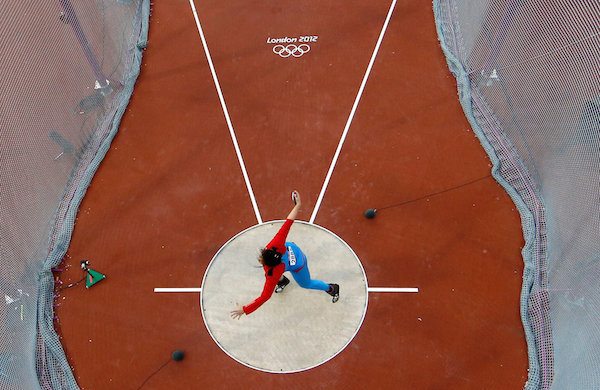

When Darya Pishchalnikova, above, a discus thrower, told the World Anti-Doping Agency that Russian sports officials were running a doping program, it sent her email to Russian sports officials. CreditPool photo by Pawel Kopczynsk

In December 2012, the World Anti-Doping Agency received an email from an Olympic athlete from Russia. She was asking for help.

The athlete, a discus thrower named Darya Pishchalnikova, had won a silver medal four months earlier at the London Olympics. She said that she had taken banned drugs at the direction of Russian sports and antidoping authorities, and that she had information on systematic doping in her country. Please investigate, she implored the agency in the email, which was written in English.

“I want to cooperate with WADA,” the email said.

But WADA, the global regulator of doping in Olympic sports, did not begin an inquiry, even though a staff lawyer circulated the message to three top officials, calling the accusations “relatively precise,” including names and facts. Instead, it did something that seemed antithetical to its mission to protect clean athletes. It sent Ms. Pishchalnikova’s email to Russian sports officials — the very people that she said were running the doping program.

The tactics of the World Anti-Doping Agency, which is partly funded by United States taxpayers, have come under international scrutiny in recent months as major doping scandals emanating from Russia have escalated into the biggest crisis in global sports. The lab director of the 2014 Sochi Olympics told The New York Times that at least 15 Russian medal winners at those Winter Games had used banned substances as part of a state-run program. Only after years of mounting clues of widespread doping did WADA recommend barring Russia’s track and field program from international competition; the global governing body for track and field is expected to decide Friday whether to bar Russia’s team from this summer’s Rio Olympics.

Interviews with dozens of officials and athletes in the Olympic movement revealed that the global antidoping watchdog mishandled allegations of widespread corruption, failed to investigate rigorously and was hampered by politics to the point that it was largely ineffective in its mission to protect the integrity of sports.

Russia’s Darya Pishchalnikova, celebrating her silver medal in the women’s discus throw during the London Olympics in 2012. CreditJohannes Eisele/AFP, via GettyImages

Multiple warning signs about Russia, including Ms. Pishchalnikova’s email, were sent to WADA over the past several years, but its response has left athletes and officials questioning whether the agency is willing to aggressively combat doping. WADA’s decision-making body is composed of government and Olympics representatives, an arrangement that presents possible conflicts because Olympics officials might not be inclined to reveal doping transgressions that could mar the integrity of the Games, while government officials could be more inclined to protect athletes from their own countries.

“There are conflicts all around the table,” said Adam Pengilly, an Olympic athlete from Britain who sits on the International Olympic Committee’s athletes’ commission.

Some WADA officials defended their handling of Russian doping allegations. They said their powers to combat doping have been limited, with scant resources and, until recently, no defined responsibility to conduct investigations. But other officials and athletes expressed a growing distrust of the agency’s leadership and a concern that it has shirked its responsibility to ensure clean competition.

“This systematic doping in Russia is being spread by WADA as sensational news, and it’s not the case,” said Arne Ljungqvist, a former medical commissioner for the Olympic committee and the I.A.A.F., the governing body for track and field.

“They could have made an investigation,” he said about the years during which WADA received repeated tips like Ms. Pishchalnikova’s email. “But they didn’t.”

Years of Clues and Calls for Scrutiny

Regarded as one of the pioneers of antidoping in the Olympic movement, Dr. Ljungqvist, 85, will soon have statues erected in his honor in Monaco, the home of the I.A.A.F., and Sweden, where he worked as a medical researcher. Yet Dr. Ljungqvist is confronted with the apparent futility of his efforts to put an end to state-sponsored doping.

“We all knew about the Russians,” Dr. Ljungqvist said over lunch in Bedminster, N.J., at the estate of the artist Sassona Norton, who has been commissioned to make the statues.

Just days before the 2008 Beijing Games, seven female Russian track and field athletes were suspended for manipulating their urine samples for drug tests. An investigation conducted by the I.A.A.F. showed that the urine the athletes provided wasn’t their own — the DNA of those samples didn’t match the athletes’ DNA.

One of those athletes was Ms. Pishchalnikova.

“It seems to be an example of systematic doping,” Dr. Ljungqvist said at a news conference in Beijing at the time. “I find it frustrating that such planned cheating is still going on. I am very disappointed.”

A year later, Russian athletes were implicated again. This time, the biathlon world champion Ekaterina Iourieva and two of her teammates were barred from the world championships after testing positive for the blood-boosting hormone EPO.

“We are facing systematic doping on a large scale in one of the strongest teams of the world,” Anders Besseberg, the president of the International Biathlon Union, said at the time.

The Russians were left to investigate themselves. The Russian Biathlon Union was fined and promised to scrutinize its own athletes.

Dr. Ljungqvist, vice president of WADA from 2008 to 2013, said he repeatedly raised concerns about Russia. The agency had considered penalties against the nation, but in the end, he said, the inherent conflicts of interests within WADA and the Olympic movement won: The matter was tabled because “it was too politically infected,” he said.

“You could say I was to blame, too,” he said. “But I’ve been there and I know how hard it is to prove doping on that scale.”

By 2011, a scientific paper written by six drug-testing experts carried further clues. Titled, “Prevalence of Blood Doping in Samples Collected From Elite Track and Field Athletes,” it examined thousands of samples collected from 2001 to 2009.

One nation — identified in the papers as Country A and known to WADA — stood out. Country A had a notably higher number of suspicious samples. According to an author of the report, Country A was Russia.

“WADA always had an excuse as to why they wouldn’t move forward,” Dr. Ljungqvist said, citing limited money and investigative resources. “They expected Russia to clean up themselves. They hadn’t fully grasped that WADA had the responsibility to do this.”

Russian sports officials have acknowledged in recent months that the country has problems with doping, but they have emphatically denied charges of a state-run drug program and dismissed whistleblowers’ specific allegations. They have said that they are addressing their doping problems and that their track program should be allowed to compete in the Rio Games.

Built-In Conflicts

When the World Anti-Doping Agency was created in 1999, its unstated purpose was to help win back the credibility of global sports in the wake of a massive drug bust at the 1998 Tour de France and a bribery scandal involving Salt Lake City’s bid to host the 2002 Olympics. Its official purpose was not to drug test or punish cheaters, but rather to serve as an independent watchdog for Olympic sports worldwide.

“They were afraid sponsor money would dry up if the Olympics were perceived as dirty,” said Robert Weiner, a former spokesman for WADA and, previously, the United States Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Sports officials and national governments gathered in Switzerland, home to the I.O.C., to discuss funding the new agency.

The United States government was especially wary about signing on to support an agency that did not appear independent. The International Olympic Committee is in charge of the Olympic Games, and derives tremendous revenue from them. I.O.C. officials — specifically the head of the marketing commission — were going to lead WADA, a doping watchdog.

Gen. Barry McCaffrey, the White House drug policy director at the time, objected loudly to what he saw as the I.O.C.’s outsize influence, and its lack of political will to unearth drug violations that could tarnish the Olympic brand.

“The I.O.C. is hiding behind WADA,” General McCaffrey said in a recent phone interview, suggesting negative attention was deflected from one organization to another. “And WADA is hiding behind a flawed structure.”

In 1999, Richard W. Pound, WADA’s first president and an I.O.C. member, bristled when General McCaffrey accused WADA of not being independent. Of course it would be independent, Mr. Pound wrote in a letter the month before the agency was established in Switzerland.

The I.O.C. hosted the agency’s first board meeting and paid for WADA’s first two years of existence.

WADA started with simple pursuits. Its charge was to standardize doping rules worldwide and create and oversee individual countries’ antidoping programs. Investigative powers were not explicitly written into the agency’s code. As time went on, many expected the organization to evolve into a more active regulator and testing body, separate from the I.O.C. and the various world governing bodies overseeing Olympic sports. That never happened.

Instead, drug testing was largely left to national laboratories. In Russia, that lab was run by Grigory Rodchenkov, who said he routinely covered up positive tests in his 10 years there.

With a budget of $28 million, WADA is funded equally by sports bodies and governments. After the I.O.C., the United States is the agency’s single largest contributor, committing about $2 million a year from the national drug control budget.

Andy Parkinson, the founding executive director of Britain’s antidoping agency, said WADA’s structure was good in theory, but too often resulted in stalemates, with Olympic loyalists and national officials rarely agreeing.

“It’s really hard to strip away the perception of that conflict,” Mr. Parkinson said.

A Whistle Is Blown

For years, Vitaly Stepanov, who worked for Russia’s antidoping agency, wondered about the motives of WADA officials. He was giving them insight into an elaborate, state-run doping program, urging them to stop it, but seemingly nothing was done.

“Everyone was telling me WADA is not an organization that fights doping,” Mr. Stepanov said. “It’s politics.”

Mr. Stepanov, who was from Russia but studied at Pace University in Manhattan, began working in antidoping education at the Russian agency in 2008, the same year the agency was officially founded. The more he learned about how the agency operated the more he realized that the Russian system was far from the accepted standard.

Sports officials told him he did not need to test some athletes because they were clean, Mr. Stepanov said. Athletes and coaches offered him bribes to dispose of positive tests. Workers at the national antidoping lab were covering up failed drug tests, and higher-ups in the Russian sports ministry were part of that scheme.

Mr. Stepanov learned even more about the ministry’s methods when, in 2009, he met and married Yuliya Rusanova, a Russian middle-distance runner who told him about her doping regimen.

“The ministry’s goal is not to make sports clean, but to win medals for the country,” Mr. Stepanov said in a phone interview.

At the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, British Columbia, Mr. Stepanov met several WADA officials in a hotel and secretly began blowing the whistle on Russia, as reported in 2015 by The Sunday Times of London.

WADA’s first reaction, he said, was “What do we do?”

In subsequent years, he sent some 200 emails to WADA, he said, telling antidoping officials everything he knew. “I work at a Russian antidoping agency that actually helps athletes dope,” he said in the phone interview. “I’m writing to WADA what’s going on, and nothing is happening.”

WADA’s response to many of his emails was, “Message received.”

Inside WADA’s offices, on the 17th floor of the former stock exchange building in Montreal, the agency’s officials were not sure how to handle Mr. Stepanov’s claims.

David Howman, the longtime director general whose corner office overlooks the St. Lawrence River, wavered. A lawyer from New Zealand, Mr. Howman said he thought to himself: “We don’t want to be the police. We can’t be the police.”

But he was aware that doping was becoming a criminal enterprise, and investigations — perhaps more than drug testing — were key to exposing cheaters. (For instance, in the sprawling Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative steroids case, known as Balco, none of the athletes found to have been doping had failed drug tests.)

When WADA was confronted with suggestions that the Russians had resurrected an East German-style system of doping, Mr. Howman said, his 70-person staff seemed inadequate. The agency did not even have an investigator, and it claimed that it did not have the authority to conduct investigations.

“It’s really up to us to monitor everyone; that’s our job,” Mr. Howman said in an interview in Montreal last month. “The idea was not to do the investigations ourselves, but to gather the information and share it with those who could actually do something about it. That’s how this whole thing started.”

But Mr. Howman eventually hired a top drug investigator from the United States: Jack Robertson, who would be the liaison between WADA and global law enforcement, and who also could help WADA untangle complicated cases.

In September 2011, Mr. Robertson was assigned to tackle doping investigations for WADA. His assignment was the entire world.

Inquiry Starts and Stops

Mr. Robertson, a former special agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration, had a résumé that would make any doper shudder.

He ran some of the United States’ biggest doping investigations in recent history, including the case that helped bring down Lance Armstrong, the seven-time Tour de France winner who was found to have doped for most of his career.

In the months before his official hiring date, he joined WADA’s legal director, Olivier Niggli, in meeting Mr. Stepanov at the Boston Marathon, to hear his account firsthand. Mr. Robertson and Mr. Stepanov met again, in Turkey, the next year.

(Mr. Stepanov was fired from Russia’s antidoping agency after raising his concerns internally. He and his wife eventually fled Russia and are now living in an undisclosed location in the United States with their young son.)

Mr. Robertson, who was gathering information, leads and potential witnesses, also encountered misfortune. His wife died of cancer and he himself had throat cancer, losing weight so rapidly that he needed a feeding tube. But he pressed on with the case.

Officially, WADA’s explicit power to investigate would begin with a new code, approved in 2013 to take effect two years later — four years after Mr. Robertson was hired as staff investigator.

Still, there did not appear to be an appetite to look deeper into Russia, especially after a new president came on board in 2014. His name was Craig Reedie, a longtime I.O.C. official who had been involved with WADA from the start. When Mr. Reedie took over as head of the agency, things changed, several staffers said.

At the same time, Russia began giving an extra donation to WADA, with no reason earmarked on WADA’s financial statements — an unusual move. In all, in the past three years, Russia has given an extra $1.14 million on top of its annual contribution, which was of $746,000 in 2015. A spokesman for the agency confirmed Russia’s contributions and said countries that choose to make additional donations have never received special treatment.

Mr. Reedie, a Scot who once led the international badminton federation, was a smooth and popular leader in the political world of the Olympics.

In antidoping circles, he is not regarded as an aggressive crusader.

“We’re not going to turn to people and say, ‘These are the rules, obey them,’” Mr. Reedie said in the lounge of the five-star Lausanne Palace hotel in Switzerland this month. He explained that WADA was better suited to offer sports federations and countries advice when they asked for it rather than pursue accusations of cheating.

Mr. Reedie’s predecessor, John Fahey, a politician from Australia, had given his blessing for Mr. Robertson to explore allegations involving Russia’s laboratories.

“There was always in our mind a deep suspicion that the government was controlling Rusada,” Mr. Fahey said in a phone interview last month, using the acronym for the Russian Anti-Doping Agency, which employed Mr. Stepanov.

When Mr. Reedie took over, the inquiry into Russia stalled, according to several people at WADA.

Case Boils Over

Mr. Robertson needed help on the case. He needed more personnel and more money to conduct a thorough investigation. But again and again, he was met with a wait-and-see attitude.

Frustrated, he forced WADA’s hand, according to several people in the organization. He leaked information on the case to Hajo Seppelt, a journalist for the German broadcasting company ARD.

Mr. Seppelt’s bombshell report, “The Secrets of Doping: How Russia Makes Its Winners,” aired on Dec. 3, 2014.

At first, Mr. Reedie told his fellow WADA officials to stand back and see if the global media picked up the story, according to several people at WADA who are not authorized to speak to reporters. But during that delay, antidoping officials spoke out, urging WADA to investigate ARD’s claims.

On Dec. 8, 2014, Travis Tygart, chief executive of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, sent a letter to Mr. Reedie and Mr. Howman at WADA, insisting that the agency had investigative power and that it needed to apply it to Russia.

The agency could not possibly hand over the case to the I.A.A.F., the track and field governing body, he said, because multiple sports were implicated in the ARD report. Also, Mr. Tygart wrote, a vice president of the track organization was reported to be a part of the cover-up.

“For WADA to sit on the sidelines in the face of such allegations flies in the face of WADA’s mandate from sport, governments and clean athletes,” Mr. Tygart wrote.

Days later, WADA commissioned an independent inquiry. Mr. Pound, who had a reputation as an aggressive antidoping crusader, was installed as the chairman.

Needing investigative muscle, the agency hired Five Stones Intelligence, a private investigations firm based in Miami and staffed with former members of the D.E.A., Secret Service, Central Intelligence Agency and Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Four months into that investigation, Natalya Zhelanova, an adviser to the Russian sports minister Vitaly Mutko, received an email from Mr. Reedie. It seemingly told her and Russia not to worry about the inquiry.

Mr. Reedie assured Ms. Zhelanova that, in his opinion, the accusations of Russian doping stemmed from a time before Russia had implemented new laws and antidoping efforts. He gave his assurance that Russia was going to be O.K. because “there is no action being taken by WADA that is critical of the efforts that I know have been made, or are being made, to improve antidoping efforts in Russia.

“On a personal level I value the relationship I have with Minister Mutko and I shall be grateful if you will inform him that there is no intention in WADA to do anything to affect that relationship,” he wrote.

When The Daily Mail in London published the email in August 2015, antidoping officials, including Mr. Pound, were stunned. The president of WADA was seemingly undermining the credibility of the independent investigation.

“I said, ‘Geez, Craig, what are you doing?’” Mr. Pound said he asked Mr. Reedie. “‘You know those people aren’t your friends, right? They’re the ones who released this to the media.’”

Mr. Reedie offered a mea culpa in another London newspaper shortly after, saying that his note to Ms. Zhelanova had been misconstrued and that WADA was not interfering with the independent investigation.

Mr. Reedie said he saw no conflicts in his dual allegiances to the Olympics and the antidoping agency. “I think we manage to do reasonably well,” he said of the current structure of the agency. “It works, and there is constant challenge from both sport and governments to everything WADA does.”

The inquiry’s findings were published in November 2015. Russia was accused of widespread government-supported doping in an explosive 323-page report that centered on track and field.

But not everything investigators had unearthed — including Pishchalnikova’s 2012 email, and WADA’s handling of it — made it into the report.

Even so, the external pressure intensified for WADA to look beyond Russia’s track and field program, and to scrutinize other countries that had come under suspicion. But Mr. Reedie was reluctant, according to several WADA officials. He said WADA did not have the money and there was not enough evidence to pursue another investigation.

“You couldn’t go forward because he was in charge,” Mr. Howman said of Mr. Reedie. “You have to rely on the people in charge, and Craig was in charge of the political stuff.”

Two years earlier, however, Mr. Howman was among the top WADA officials who had received the email plea from Ms. Pishchalnikova. Mr. Reedie was on the agency’s Foundation Board at the time, but he was not yet president.

In her 2012 email, Ms. Pishchalnikova named Dr. Rodchenkov, the antidoping lab director whose facility had recently been flagged by WADA for suspicious test results. She said he was substituting out athletes’ steroid-laced urine with clean urine. “I have proof,” the 2012 email said.

The agency’s decision to forward the email to track and field officials — including Russian ones who were implicated in the allegations — was a function of protocol. In spite of having hired a staff investigator, WADA did not at that time see itself as capable of conducting investigations, the agency has said.

Four months after Ms. Pishchalnikova wrote to WADA, the Russian track and field federation banned her for 10 years. She is retired from competition and living in Russia. Attempts to reach her were unsuccessful.

Mr. Reedie — who said he had never heard of Ms. Pishchalnikova’s email — said he required proof before initiating investigations. “We need people to come to us with evidence, and then we will investigate,” he said in an interview.

He said the decision to allow Russian track and field athletes to compete in the Summer Games was entirely up to the sport’s governing body. “That’s their problem,” he said. “I’m one of the few people who doesn’t wake up in the morning and think only about Rio.”

Meanwhile, athletes have in recent months agitated for further inquiries.

“Clean athletes are at the point where we can’t have faith in the system,” said Lauryn Williams, a United States sprinter and bobsledder. She added that she was disappointed that the November report had not immediately spurred a broader inquiry.

“Who’s defending us?” she said. “Who’s on our side?”

After Ms. Williams and other athletes from around the world sent a letter to WADA and the I.O.C. last month detailing their concerns, the agency announced a new independent investigation into the allegations about cheating at the Sochi Olympics made by Dr. Rodchenkov, the lab director.

Other specialized inquiries, such as one into accusations of doping by Chinese swimmers, have been opened. “Investigations have become the flavor of the month,” Mr. Reedie said.

Mr. Howman, who is leaving WADA this month, said that only after the Sochi investigation is complete — roughly two weeks before the Rio Games are scheduled to begin, it is expected — should WADA be judged on how it has handled the cases.

“It’s a really tense time because no one wants to mess it up,” Mr. Howman said.

As for Mr. Reedie, his term as WADA president runs through the end of the year. Many antidoping experts and athletes see his dual role as a vice president of the I.O.C. as emblematic of the conflict they say is derailing WADA.

After the recent interview in Lausanne, Mr. Reedie handed a reporter his business card. He apologized that, with its five-colored Olympics rings logo, it was an official I.O.C. card, not a WADA one.

“It’s the only one I can give you,” he said.