Lifelong language study can change a person. It enriches one’s life, especially if it is a relatively difficult language requiring assiduous study and if it continues to be used. I began studying Arabic when I was 18 years old, while an enlisted man in the U.S. Army; almost 40 years later, I am still studying Arabic.

The student can often recall important milestones in that long journey to language fluency, the first word you wrote (in my case, it was “nightingale,” بُلْبُل), the first “real” book you read (for me, it was the collection of animal fables called Kalila wa Dimna, originally a Sanskrit work translated into Persian and then Syriac and then into Arabic by the Abbasid bureaucrat Ibn Al-Muqaffa), and the first Arabic verse you memorized (Abu al-Tayyib Al-Mutanabbi’s “when you see the lion baring his teeth, do not think he is smiling at you”).

Because I had the good fortune of actually using my language in my work for many years, and still doing so, and of living and working in the Arab world for many years, that initial Arabic study was enriched by real-life encounters with some transcendental figures – Muhammad Al-Maghut, Muzaffar Al-Nawab, Abd Al-Rahman Munif, Mamduh Adwan, Elias Zayyat. But mostly it was enriched by interactions with ordinary, good people whom you meet by chance – a local Syrian policeman who guided my family and me to the difficult-to-find the ruins of the 13th century Assassin stronghold of Qalaat Al-Kahf,[1] or the Good Samaritan in Homs who fashioned a temporary spare part for our broken-down American-made Honda Accord and refused to accept payment for it.

I have also been blessed to see some of the interplay where cultures enrich each other. To have known, even briefly, the great Kordofan singer/musician Abdel Gadir Salem was more exciting to me than meeting a head of state.[2] In Damascus, I saw Arabic versions of both Camus’s Caligula (with Jihad Saad in the starring role) and Tennessee Williams’ Streetcar Named Desire (with Kingdom of Heaven actor Ghassan Massoud). And I can still recall being lucky enough to see protean director Haytham Haqqi film some of his Aleppo-based serial Khan A-Harir in the evenings inside the Suq of old Aleppo, an area now cruelly destroyed by the Syrian civil war. These were the same years that some Westerners discovered, and made available to the world, the at the time yet-untranslated riches of Syrian literature, by authors such as Zakaria Tamer, Nabil Suleiman, and Ulfat Idilbi.

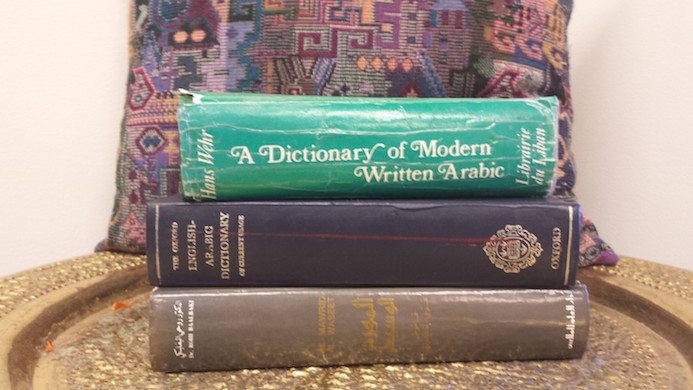

The Arabic student can often be marked by his tools of the trade. There is a whole generation of Americans that used the “orange book” published by the University of Michigan. As for dictionaries, I have three dog-eared copies of Hans Wehr’s Arabic-English Dictionary, whose fourth and latest English edition goes back to 1979, and two Oxford dictionaries (Arabic and English-Arabic). I love my Hans Wehr, having grown old with it, but many now-commonly used words in the Arabic media are not found in its pages.[3] An old edition of Al-Munjid (Arabic-Arabic) dictionary, published in Beirut, completes my collection. Wehr’s seminal work, of course, first began in German and was translated into English.

The August 20, 2015 issue of the Israeli daily Haaretz highlighted still another major contribution to the study of Arabic in a non-English language, this time in Hebrew. This latest development could help bridge the language gap among the world’s languages for a new comprehensive and reliable dictionary of modern Arabic, should it make its jump into English.

Dr. Meir Bar Asher, Professor of Islamic Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, notes in this Haaretz article that Professor Menahem Milson’s[4] vast Online Arabic-Hebrew dictionary (arabdictionary.huji.ac.il) is “a superb lexicon of modern Arabic that can significantly contribute to the improvement of Arabic-language teaching in Israel.” Milson has been the academic advisor of MEMRI since its inception, and hence he benefited from the queries sent to him by dozens of MEMRI researchers who constantly follow the Arabic media, both printed and electronic. They became, in a way, some of the “field workers” of the dictionary.

Milson is also, of course, a world authority on the literary works of Naguib Mafhouz; his book on Sufism, A Sufi Rule for Novices (emanating from his Ph.D. dissertation) is an important source for the study of Sufism. Dr. Milson’s decades-long work replaces the 1947 Arabic-Hebrew Dictionary of Modern Arabic compiled by David Ayalon and Pessah Shinar (most of Hans Wehr’s original work was from roughly the same time period). Rather than updating the older work, a new dictionary drawing from the considerable changes occurring in both languages over more than 50 years eventually arrived.

Dr. Bar Asher adds:

Milson’s dictionary is, therefore, very timely. Neither personal computing nor the Internet existed in earlier generations, and their advent has inevitably given rise to completely new terminology. Another realm that has produced a spate of new words and expressions is politico-religious thought: Islamic groups and organizations characterized by an Arabic style that combines old and new have generated a wealth of fresh terminology. The language of these thinkers is notable for its copious use of ancient Arabic Muslim terms to which layers and shades of new meaning have been added, and new words and expressions have also been coined. This constantly emerging profusion is diligently reflected in Milson’s new dictionary.

The dictionary is concerned mainly with modern standard Arabic, and especially with the form of written and spoken language used in the Arabic media. This type of Arabic was not created in a vacuum: it is firmly rooted in a rich literary history extending back over more than one thousand four hundred years. It draws upon the language of ancient Arabic poetry (including pre-Islamic poetry) and stems also from the language of the Koran, Hadith literature and adab (a form of eclectic and encyclopedic belles lettres). Moreover, the spread of fundamentalist Islam over the past generation has brought large sectors of the population closer to the classical registers of the Arabic language, and members of these circles frequently season their speech and writings with quotations from the Koran and the Hadith. Their mode of speech has likewise introduced into the media expressions and turns of phrase from the literature of Muslim religious law and theology that were considered archaic until just a generation ago. Today, however, political discourse is incomprehensible without a knowledge of them.

The author notes how Milson provides context and definition for some hoary words that still have, unfortunately, a very contemporary understanding – including one I have frequently used on pan-Arab broadcast media appearances:

We now move on to a number of entries concerning history and literature. On looking up the word qamīs (“shirt”) we find the expression qamīs ‘uthmān, for which two definitions are given. The first: “Uthman’s shirt (the shirt stained with the blood of Uthman, the third caliph, who was murdered by rebels),” with the accompanying explanatory note: “The Umayyads used it in order to justify their war against their rivals, who, they claimed, were involved in Uthman’s murder.” The second definition, which is unique to Milson’s dictionary, reads: “by extension: a pretext for war or vengeance, a cause for aggression.” It is worth mentioning that this expression, in its metaphorical sense, is very frequently used in the Arabic media, and appears almost daily in articles and features. Nonetheless, it is not to be found in most modern dictionaries of Arabic (the new Oxford Dictionary does not have it), and Milson has done well to include it.

In addition to mining thousands of terms and examples drawn from the rich and beautiful trove of Arabic literature through the centuries, Bar Asher notes that the Milson dictionary draws from very recent history and elucidates very recent terms:

We find entries such as taslī’ and tashyī’, meaning “objectification, commoditization” (hence taslī’ al-mar’a and tashyī’ al-mar’a – “the objectification / commoditization of women”); ‘awlama (“globalization”); raqmana (“digitalization”) and similar terms. The term dā’ish (“ISIS”) is likewise included, and is defined as follows: “an acronym for il-dawla al-‘islāmiyya fi al-‘irāq w-al-shām (‘the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Shām’).” The translation is accompanied by a note: “This belligerent Islamic movement that advocates world jihad was established in Iraq in 2006; several years later it extended its activities into Syria. The term dā’ish, although frequently encountered in the media, is not used by the movement’s spokesmen.” Another example from the same area of meaning is the verb akhwana, which means “to impose the doctrines of the ikhwān (i.e., the Muslim Brotherhood) upon…” or “to make [someone / something]ikhwāni (i.e. belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood).” Needless to say, these terms are not found in the other dictionaries reviewed above; in Milson’s dictionary, however, there are hundreds of such expressions.

Dr. Ben-Asher makes a strong case that researchers and students have felt the need for an adequate new Arabic dictionary. He notes that Al-Munjid, which was published in Beirut in 1908, and justly remained for over a hundred years the most reliable and practical dictionary for readers of Arabic, is finally showing its age. A new edition, entitled Al-Munjid fi al lugha al-‘arabiyya al-mu’ās ira (Al-Munjid of Contemporary Arabic), published in Beirut in 2008 exactly one hundred years after the appearance of the first edition, offered only a partial response to expectations raised by its evocative name (al-munjid means “the helper”):

“Hans Wehr’s Arabic-English Dictionary, which is a translation of the Arabic-German lexicon compiled by the same author, is still regarded as the best comprehensive dictionary of modern Arabic, but it, too, is very considerably outdated (the fourth and most recent English edition dates back to 1979, while the fifth German edition was published in 1985), and present-day users will find it lacks the abundance of new words and terms that have entered Arabic over the past thirty years. The more recently published (2014) Oxford Arabic Dictionary likewise has deficiencies. One of the main disadvantages of most of these dictionaries (apart from that of Hans Wehr) is that they are not based upon texts, but instead rely primarily on existing lexicons.”

A modern Arabic dictionary must include numerous expressions in the fields of Islamic tradition and jurisprudence which now abound in contemporary Arabic public discourse. These are often missing from many of the modern Arabic dictionaries. Milson’s dictionary successfully covers this important area. For example:sadd al-dhara’i’ “prohibiting the use of means,” that is, in Islamic jurisprudence, prohibiting something that is not reprehensible in itself because it may become a means to something which is prohibited.

Recent news that the Israeli Knesset has made the study of Arabic compulsory beginning at the age of six means that the number of Jewish Israelis who can understand and appreciate Arabic will greatly increase.[5] This can only be good. Menahem Milson’s online Arabic-Hebrew dictionary will serve as a superb lexicon of modern Arabic for those students, scholars and searchers who seek to respectfully understand more and who will embark on a life-long journey with the Arabic language. I have certainly found the language and the culture of the peoples of the Arab world to be a good and congenial companion for most of my adult life.

It is to be hoped that this vast and monumental scholarly undertaking by Dr. Milson will soon find another long and productive life in English and other Western languages, just like the great work of that German professor working long ago in the 1940s and 50s, encouraged and nurtured many generations of students of Arabic.[6] This huge and invaluable endeavor should be translated into English.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice-President of MEMRI.

Endnotes:

[1] Monumentsofsyria.com/places/qalaat-al-kahf-%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%87%D9%81/.

[2] Youtube.com/watch?v=VuztId3TWHk.

[3] Daily Star (Lebanon), June 13, 2014.

[4] See http://www.memri.org/menahem-milson-chairman-of-memris-board-of-advisors.html.

[5] BBC.com, August 24, 2010.

[6] Middle East Institute blog, mideasti.blogspot.com, June 16, 2014.