The mustachioed man entering Raghadan Palace was flanked by two assistants. He seemed younger than his seventy years and the hat he donned concealed his graying hair. His visit with Hussein, then King of Jordan, was kept in total secrecy. The man was an Israeli, and in those days—November of 1993—the two countries hadn’t yet established diplomatic relations. In fact, officially, they were still in a state of war.

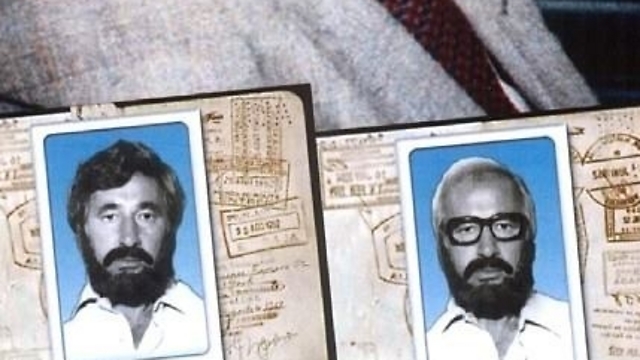

The fake mustache and hat made it hard to recognize one of the most recognizable Israelis in the world: Shimon Peres, who was then the foreign minister. His assistants were deputy Mossad director Efarim Halevy and Avi Gil, his chief of staff.

“I couldn’t help but laugh as I glued the mustache to my face,” wrote Israel’s former president in his autobiographical book titled No Room for Small Dreams, which will published in Israel and around the world this month to mark the one year anniversary of his death.

“I thought back to the sunglasses we put on Moshe Dayan to hide his eye patch; of the wide-brimmed hat we affixed to Ben Gurion’s head to hide his characteristically chaotic white hair. How many times in my life had we put on such silly disguises in pursuit of something that others were certain was impossible? These were some of the very best memories of my relative youth. And knowing at seventy that I was still in the fight, still battling for the future of Israel, gave the mustache a certain power. I looked like an actor in a low-budget stage show, but I felt like the tip of the spear,” Peres wrote of his meeting with the Jordanian king.

Peres dons mustache and fedora to visit Amman for peace talks with Jordan.

This meeting, however, in a royal palace overlooking Amman’s old city, was not the pair’s first. Seven years prior they had secretly convened in London.

“Yet from the moment the conversation began,” Peres recalled, “it felt like it had never quite ended. We treated each other as old friends, and found once again a common view of the future.”

A year later, on October 26, 1994, that view became a reality. In a festive ceremony held in the Arava valley near Eilat, in front of then US President Bill Clinton and 5,000 other guests, King Hussein and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin signed the historic peace accord between Israel and Jordan.

A copy for Mongolia’s foreign minister

Ayelet Frish, who worked alongside Peres for more than a decade, served as spokeswoman during his tenure as Israel’s president and now serves as the director of the Innovation Center at the Peres Center for Peace and Innovation, said Peres flatly refused to pen an autobiographical memoir for years.

“When I asked him why he won’t write one,” said Frish, “he said he simply couldn’t bear to write about himself and preferred others do that instead.”

In the last months of his life something changed, however. “We thought he’d live to at least 100,” Frish reminisced. “He kept on working every day from five in the morning until midnight, and just two weeks before he died, he was the keynote speaker in a conference in Italy. But His Excellency the President—I still call him that—must have felt his days were numbered. He understood he was down to the last few grains of sand in the hourglass, so to speak, and it was now his responsibility to pay his vision forward, to the younger generation of not just Israel but the entire world. He agreed to write only after becoming convinced the book’s goal wasn’t to simply glorify him, but to tell the awe-inspiring story of the State of Israel from his own point of view.”

The goal then became publishing the book in as many languages as possible. “We wanted to reach young executives in China and the leaders of the future in Africa,” Frish said.

It was precisely for that reason the book was written in English, and will be published early next week by HarperCollins, one of the world’s largest book publishers. There are also talks on translating it to dozens of other languages, including Arabic.

“Even the Mongolian foreign minister has already asked for a copy,” Frish said.

The book was finished about a month before Peres passed away at 93 on September 28, 2016. “For several weeks, he secluded himself in a Tel Aviv apartment with staff members and a documenter from the American publisher and just pieced together his life’s story again,” Frish said about the writing process. “It was quite an experience to get a first-person account of how Israel came to be from practically nothing thanks to people like him. Thanks to the daring, the willingness to take risks, not fearing failure and the recognition our greatest capital lies in our heads and not the land.”

Recommendations from Albert Einstein

This attitude is also reflected in the story of the creation of the Dimona nuclear reactor, to which an entire chapter in the book is dedicated.

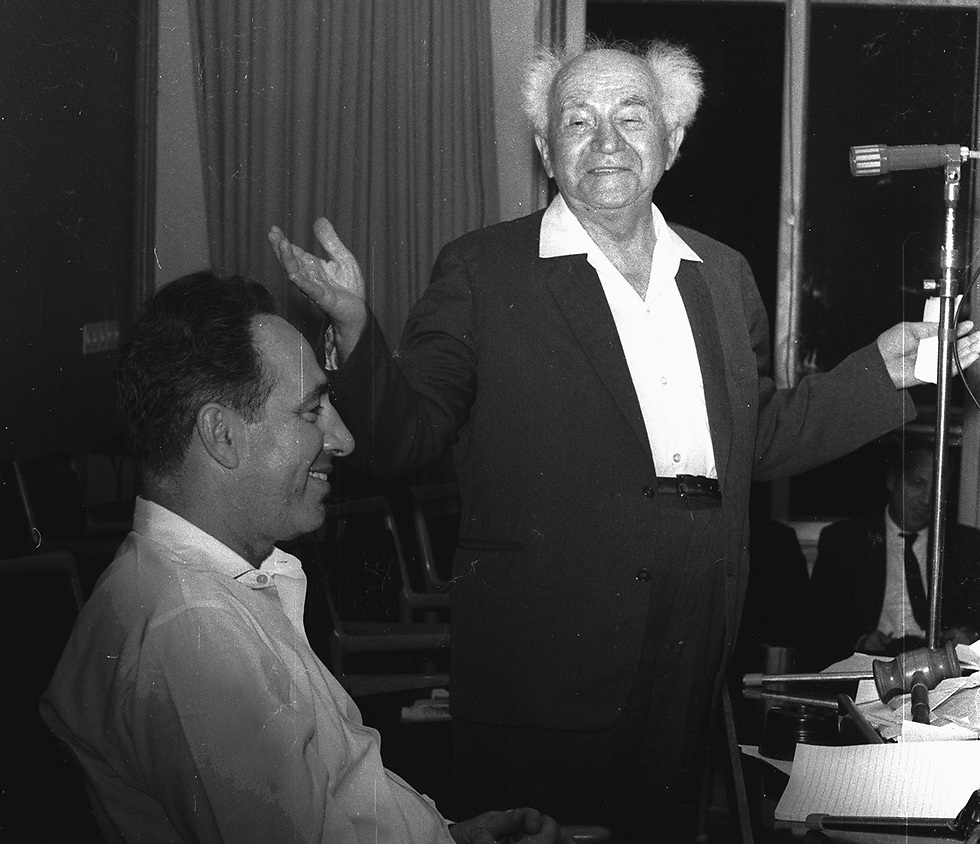

The vision was David Ben-Gurion’s. The application was placed in the hands of scientists, headed by Professors Ernst David Bergmann and Israel Dostrovsky, and the men of execution, chiefly Emmanuel (Manes) Pratt.

No person is more synonymous with the Israeli nuclear project, however, than Shimon Peres. As director-general of the Ministry of Defense and then deputy minister, he was entrusted with the country’s most ambitious—and secretive—project, accompanying it every step of the way: from the complex and sensitive negotiations with the French, who gave the reactor to Israel, through raising the immense funds required to provide Israel with its nuclear deterrence, and ending with locating, training and guiding the reactor’s scientists and administrators.

To make this project a reality, Ben-Gurion and Peres were forced to handle not only France’s inner political turmoil, which almost thwarted the deal, but also fierce objections from within Israel’s own ranks.

“Golda Meir insisted such a project would hurt Israel’s relationship with the United States, while Isser Harel, the Mossad chief, raised fears of a Soviet response,” Peres recounted. “Some predicted an invasion by ground forces, while others envisioned an attack from the air. The head of the foreign relations committee said he feared the project would be ‘so expensive that we shall be left without bread and even without rice.’ For his part, Levi Eshkol, then the finance minister, promised we wouldn’t see a penny from him.”

At times, it seemed like a mission impossible. “Innovation, I have come to understand, is always an uphill climb. But rarely does it find so many obstacles arrayed against it at all once. We had no money, no engineers, no support from the physics community or the cabinet or the military leadership or the opposition. ‘What are we going to do?’ Ben-Gurion asked me late one night, as we sat quietly in his office. It was the operative question. What we had was a French promise—only that, and each other.”

One of the project’s most critical phases was fundraising. “We took to the phones and made passionate, personal (and highly confidential) appeals to some of Israel’s most reliable donors from around the world. In short order, we had raised enough money to cover half the cost of the reactor—more than enough to start building our team,” the former president wrote.

After raising the funds for the Dimona project, the time came to find the right people to actually staff it. “We were lucky to count Israel Dostrovsky as one of our early members,” Peres wrote in his memoir. “A decorated Israeli scientist, Dostrovsky had invented a process for manufacturing heavy water and sold it to the French years earlier. But even he could not compete with the brilliance of Ernst David Bergmann, whom I approached to join the mission. In 1934, legend had it that Chaim Weizmann sought Albert Einstein’s recommendation for a scientist to lead his newly created institute outside Tel Aviv. Einstein gave him only one name—that of Ernst Bergmann.

“With Bergmann and Dostrovsky, we had scientific know-how. But what we needed even more was a project manager whom we could trust with such a delicate task. We needed a pedantic stickler, someone allergic to compromise—especially given the dangers involved in radioactive work. And yet we also needed someone who was agile, someone willing to take on a project for which he would certainly lack expertise. There was a natural tension that existed between those requirements, one that quickly whittled down my list of candidates to one.”

That one man was Col. (res.) Emmanuel (Manes) Pratt. “We met during the War of Independence, when we worked together on the frantic building up of the IDF,” wrote Peres about Pratt. “He was consistently and insistently precise, the kind of man for whom perfection is not a distant pursuit, but a minimum ante. He was quickfooted and quick-witted, and he demanded in those around him the same relentless work ethic he practiced.

“When I explained my proposal and the position I wanted him to consider, he looked as though he could have struck me. He couldn’t disguise his disbelief. ‘Are you crazy?’ he demanded. ‘I don’t have the slightest idea what it would take to build a reactor. I don’t know how it looks; I don’t even know what it is! How could you expect me to take charge of such a project?’

“‘Manes, look: I know that you don’t know anything yet. But if there is somebody in this country who can become an expert after studying it for three months, that person is clearly you,'” Peres said he replied to the bewildered administrator.

“I suggested that we would send him to France for three months to study nuclear reactors alongside the experts who would help us build one. And I promised that if he returned to Israel after that time still uncomfortable with his fluency in the topic, he could simply return to his previous work. With no requirement for a permanent commitment, Pratt ultimately agreed. And to no one’s surprise, when he returned from France, he did so as the finest nuclear expert we would ever come to know.

“With the leadership in place, I turned to the work of building the rest of the team. I knew the older generation of physicists was deeply opposed to our efforts, but I suspected we could find students and young graduates who were eager to pursue such an ambitious project. Having been turned away by the Weizmann Institute, I turned to the Israeli Institute of Technology, in Haifa, known as the Technion. There I found a group of scientists and engineers who were eager to take the leap alongside us. Like Pratt, I intended to send each Technion recruit to France for a period of study.

“The students went off to France to study nuclear engineering— and I joined them, not as the leader of the project but as a peer. Chemistry and nuclear physics were challenging subjects, to be sure, and I came to them without any previous training. But I felt it essential to gain a degree of mastery in the science that would be driving the project. And so, alongside these young physicists, I spent day and night studying atomic particles and nuclear energy, and the process required to harness its power.”

The power of ambiguity

In the late fifties, Peres decided to take center stage at last and ran on Mapai’s Knesset ticket. After receiving Ben-Gurion’s blessing, on November 3, 1959—at age 36—he began his first political office, ascending to the role of deputy minister of defense.

“By the summer of 1960, the Dimona project had moved forward apace,” reminisced Peres. “France was upholding its end of the agreement, and the French and Israeli workforce had broken ground on the barren plateau. That September, I was in West Africa on orders from Ben-Gurion, as part of an effort to build stronger ties between Israel and the broader continent. But the trip was cut short. I received an urgent cable, ordering my immediate return to Israel. There was no indication of what the emergency entailed.

“When I arrived at the airport in Tel Aviv, Isser Harel, the Mossad chief, was waiting with Golda Meir in a helicopter nearby. We barely spoke on the ride to Sde Boker, where Ben-Gurion was awaiting Harel’s report.

“‘Explain the situation,’ Ben-Gurion demanded as we gathered in his sparse and humble ‘hut.’ Harel relayed two pieces of intelligence. First, Mossad had learned a Soviet satellite had recently flown over Dimona and photographed the construction site. Second, they received word the Soviet foreign minister had made an unexpected visit to Washington. In his estimation, these two facts were linked—and damning. He was concerned the Soviet government would claim our work in Dimona was nefarious, that their foreign minister had likely demanded US intervention while in Washington. Israel, it seemed, was about to be confronted by the world’s only two superpowers.

“‘What is your recommendation?’ Ben-Gurion asked of the group. Harel believed Golda—or even better, Ben-Gurion himself—should fly to Washington at once and give assurances to the White House. Golda agreed, believing the situation to be dire, perhaps insurmountably so. I listened intently and sympathized with their concerns, but when Ben-Gurion asked me my opinion, I had to be honest.

“‘So what if a Soviet satellite has flown the Negev? What has it photographed? Just holes in the ground,’ I explained. We were still in the first stage of the project, an extensive excavation followed by the laying of concrete foundation. ‘What can be proved from that?’ I asked. ‘After all, every building needs foundations,” Peres remembered he said in the meeting.

“If Ben Gurion flew to Washington and revealed the work we had undertaken, it would destroy our relations with the French,” he concluded. Ben Gurion is said to have concurred.

Just three short years later, Peres found himself standing in the Oval Office opposite US President John F. Kennedy.

“I had traveled to Washington to conclude a deal for the purchase of antiaircraft missiles from the US government. Kennedy’s Near East advisor, Mike Feldman, had invited me to the White House, along with our ambassador, Avraham ‘Abe’ Harman. When I’d arrived, I was told—quite unexpectedly—that President Kennedy wanted to speak to me. He knew I was in charge of Israel’s nuclear program and, according to Feldman, he had a number of questions. Because I wasn’t the head of government, it was against protocol for President Kennedy to take a formal meeting with me.

“Instead, I had been escorted through the side entrance of the West Wing of the White House, and around a back corridor to the Oval Office. I was meant to have bumped into President Kennedy along the way, who would then, out of courtesy, invite me to have a conversation,” Peres wrote.

Peres then went on to describe his meeting with the young Commander-in-Chief. “Behind his desk in the Oval Office, Kennedy looked stiff and deliberate, and though he had ways of disguising it, I could tell he was coping with pain. He stood up to shake my hand, then offered me a place on the sofa. He sat adjacent to me, in a padded wooden rocking chair.

“‘Mr. Peres, what brings you to Washington?’ he asked, in his familiar accent.”

“I told him I was there to purchase the Hawk missiles, which Israel deeply appreciated. But I added we hoped this arms agreement was just the beginning. We needed support—as much as the Americans were willing to give.

“‘Go talk to my brother (then Attorney-General Robert Kennedy) about that,’ he replied, shifting attention to the matter of his greater concern. ‘Let’s you and I talk about your nuclear facility.'”

Kennedy then laid out all of the intelligence the US government had gathered on the nascent Israeli nuclear project.

“When he finished, it felt as though there was nothing that the Americans didn’t know about the construction. And yet Kennedy knew that mystery remained, and he was preoccupied with rumors,” Peres remembered.

“‘You know we follow with great concern any indication of the development of military capacity in that area,’ Kennedy said. ‘What can you tell me about this? What are your intentions as they relate to nuclear weapons, Mr. Peres?'”

“I hadn’t expected to see the president, let alone to be asked such a question,” Peres recalled. “Under the circumstances, I did my best to reassure him. ‘Mr. President, I can tell you most clearly we shall not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons to the region.’

“My impromptu statement to President Kennedy became Israel’s long-term policy. It has been described as ‘nuclear ambiguity,’ quite simply the decision to neither confirm nor deny the existence of nuclear weapons.”

This ambiguity was—and still is—Israel’s official policy regarding its nuclear capabilities.

Peres explained exactly why. “The existence of Dimona may have increased our enemies’ desire to destroy us. But the suspicions it generated stole from them the belief they could overpower us. Over time, we learned there is tremendous power in ambiguity. By the 1970s, the conventional wisdom among leaders in the Arab world was that Israel possessed nuclear weapons. What they lacked in evidence, they filled in with rumors. We did nothing to confirm such suspicions, and likewise nothing to dissuade them. Believing Israel had the power to destroy them, our enemies one by one abandoned their ambitions to destroy us. Doubt was a powerful deterrent to those who desired a second Holocaust.

“In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War, Egypt and Syria caught Israel by surprise, leaving our cities vulnerable to catastrophic attack during their coordinated offensive. And yet neither country dared to attack the heart of Israel, even when they had the capability to do so; Egyptian troops were ordered not to go beyond the Mitla Pass in the Sinai, while Syrian troops stayed in the Golan Heights. Years later, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat acknowledged he feared an attack on the cities of Israel would have justified a nuclear response.”

Far from being only an instrument of war, or dangling the threat thereof, nuclear deterrence also turned out to be a tool for peace. Peres backed this assertion in his book. “In November 1977, Sadat made his historic visit to Jerusalem, one that would culminate in a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. Upon his arrival, the first issue he raised was Israel’s nuclear program. And when he faced criticism from his fellow Egyptians, he described a nuclear attack as the only other possibility. ‘The alternative to peace is terrible,’ he insisted.”

In 1995, Peres—then the foreign minister—arrived in Cairo for a meeting with his Egyptian counterpart Amr Moussa. “We’d come to know each other well over the years, and after a lengthy conversation, he raised an issue still clearly on his mind. ‘Shimon, we are friends. Why don’t you let me go have a look at Dimona? I swear I will not tell anybody,'” Peres said Moussa told him.

“‘Amr, are you crazy?’ I replied. ‘Suppose I shall bring you to Dimona, and you see there is nothing there? Suppose you stop worrying? For me, this is a catastrophe. I prefer you remain suspicious. This is my deterrence.'”

Peres summed up this chapter of his autobiography—and life. “I had spent so much of my youth trying to secure Israel for its people. But this was a different kind of security altogether. This was the security of knowing the state would never be destroyed—a first step toward peace that started with peace of mind. In this way, I felt that our work on Dimona, an effort once marked for certain failure, had fulfilled the covenant I had made with my grandfather, but on a far grander scale: to always remain Jewish and ensure the Jewish people always remain.”

The Rehovot ‘golem’

Innovation was well-known to be one of the pillars of Peres’s worldview. Contrary to popular belief, however, that bug accompanied him throughout his entire life and not just during his twilight years.

“Peres spearheaded the vision of the ‘startup nation’ as far back as the fifties and sixties,” said Ayelet Frish, citing the “golem” story as an example.

The “golem” was one of Israel’s very first self-manufactured computers. It took up three gigantic rooms in the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot and required an entire crew of engineers and scientists to operate. The year was 1963 and, save for some technological fanatics, nobody really knew what a computer was.

One of those fanatics was Deputy Minister of Defense Shimon Peres. When he visited the Weizmann Institute that year and saw this clunky monstrosity, he immediately realized what he was seeing was a vision of the future.

Peres vividly recollected his thoughts on the computer. “This is what the army needs, I thought—one computer could replace one thousand soldiers and give us more data than they alone could gather. I spent many days and nights with the group that managed the computer, learning how it worked, and how it might work on behalf of the military. I returned to the ministry thoroughly convinced of its value, insisting we purchase one of our own.

“‘Where are you going to put it?’ one general said incredulously of the enormous machine. ‘What would we do with it?’ another asked. ‘Can you take a computer with a division into the field? Of course you can’t! We don’t even have enough tanks, and you’re talking about computers. A tank shoots. It fires. What on earth can a computer do?'”

The rest, as they say, was history.

The Fantasy Council

When an Air France flight was hijacked and rerouted to Entebbe, Uganda in July of 1976, Peres was the minister of defense in the government of Prime Minister Rabin.

In the chapter dedicated to Operation Entebbe, Peres described the meeting in which he asked security establishment officials to present him with a plan to extricate the hostages.

“We have to use our imagination, and examine any idea, as crazy as it may seem,” he insisted to the assembled army men.

“We have no plans,” one of them responded.

“Then I want to hear the plans you don’t have!” he replied.

When the meeting adjourned, three alternative courses of action were formulated. “The first came from (IDF chief of operations) Kuti Adam, who argued that if we couldn’t rescue the hostages in Entebbe, we should try to get the hostages to come to us. If we could convince the hijackers to fly to Israel—perhaps in the belief we would participate in an exchange of hostages for prisoners upon their arrival—we could conduct a raid similar to the one we’d executed so successfully with the Sabena flight.

“It was a creative approach, to be sure, but it assumed we had leverage where we likely did not. Surely the terrorists had chosen Entebbe for a reason—not only because of its distance from Israel, but because they had the support of Uganda’s president Idi Amin, who we knew had greeted the terrorists as ‘welcomed guests.’ It seemed implausible they would give up such an advantage. Besides, the Sabena rescue operation had been widely publicized; it was no longer a secret playbook.

“The second approach, proposed by (IDF chief of general staff) Motta Gur, assumed the rescue would have to take place in Entebbe. He described a scenario whereby Israeli paratroopers would sneak into Entebbe by way of Lake Victoria, launch an unexpected attack on the hijackers, and remain to protect the hostages.

“This plan had the virtue of practicality, in that it described a scenario the IDF was more than capable of executing. But what it lacked, fundamentally, was an exit plan. Once the hostages were rescued, there would be no way to evacuate them. If the Ugandan army chose to respond, it could surely send a force large enough to overpower even our finest commandos.

“The third approach was by far the most fantastic in terms of imagination. Maj.-Gen. Benny Peled, who was the commander of the Israeli Air Force, suggested that Israel conquer Uganda—or at least Entebbe itself. Israeli paratroopers would temporarily occupy the city, the airport, and the harbor, after which the hijackers would be attacked and killed. Having secured the area, the air force would land its Hercules military transport plane at Entebbe airport and use it to bring the hostages home.

“On its face, the plan seemed preposterous. Gur described it as ‘unrealistic, nothing but a fantasy.’ The others agreed. And yet, of the three proposals, it was the one that had me most intrigued. Aside from its scale and ambition, it struck me that there was nothing about Peled’s plan that was disqualifying. Unlike Gur’s plan, this one included a strategy for evacuating the hostages. And unlike Kuti’s plan, it didn’t require us to manipulate the terrorists into acting against their interests. Indeed, when the meeting was over, Peled’s plan was the only one I hadn’t dismissed.

“Shortly after, I convened a meeting of my own, one that Gur would coin the ‘Fantasy Council.’ My intent was to bring the most creative thinkers in the IDF together so that we could consider every known option and be bold in thinking about options that did not exist.”

Among the alternative operational courses of action weighed, for example, was one suggesting parachuting forces into Lake Victoria, which was disqualified when it was discovered the lake was infested with alligators.

The IDF never received orders to occupy Entebbe, of course, but the rescue plan that was eventually approved by both Prime Minister Rabin and Peres was arguably no less daring.

The rescue operation—carried out by the air force, Sayeret Matkal and additional forces—was considered an enormous success. And even if it hadn’t, Peres stressed, “the decision would still have been correct. This is one of the hardest things for some leaders to understand: a decision can be right even if it leads to failure.”

Nevertheless, the moment Peres was informed the Sayeret Matkal commander Lt.-Col. Yoni Netanyahu was killed during the operation was one of the hardest of his career. It came only shortly after the announcement saying Israeli Air Force planes took off from Uganda with the hostages in tow.

“I returned to my office and, at last, planted myself on the couch, ready to catch the first sleep I’d had in days,” Peres wrote of the moments leading up to the announcement. “I heard a rustle at the door, and opened my eyes to see Gur standing in front of me. The last time I saw him, he was smiling and cheering. Now his face was sullen and sunken. It was the face of a man who had learned something tragic, but couldn’t find the words to share it.

“‘What is it?’ I asked, as I got to my feet.”

“‘Shimon,’ he said meekly, ‘Yoni’s gone. He was struck by a bullet from a sniper in the control tower. It pierced his heart.’

“I turned away from Gur and faced the wall. In all of the tension of the week, I had steeled myself, holding my emotions tightly in place. I had no words for Gur, nor did he have any more for me. Instead, he left my office and I burst into tears.”

Like the army chief of staff’s headquarters

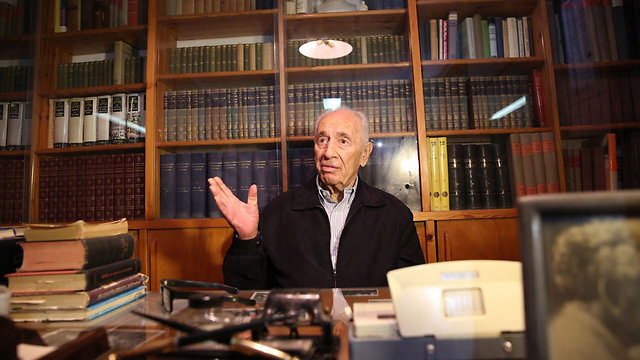

A year after Peres’s passing, his office in the Peres Center for Peace and Innovation by Jaffa’s shore continues ticking as if its occupant only just stepped out for a moment and is expected to return in no time.

“It’s like the chief of staff’s headquarters,” said Frish. “The entire Peres team comes into work every day, continuing to work on the projects he created and fulfilling what he tasked us with doing.”

“I can just envision my father stepping into the office now, loosening his tie, sitting down in the chair and carrying on working as if he’d never left,” said Chemi, Peres’s son.

“The Peres family—chiefly his children Tziki Walden, Yoni and Chemi—harnessed themselves to working on the book around the clock, knowing it was so important to their father, in order for the it be completed on the one-year anniversary of his passing,” noted Frish.

Attorney Or Kornhauser, the book’s project manager, also works around the clock. She flew with Chemi to the US last week in anticipation of the book’s launch and promotional tour.

“It’s going to be an international affair,” she said. “Launch events are already booked in San Francisco, Detroit and Atlanta, and that’s just the beginning. CEOs of some of the world’s largest companies intend to purchase bulk copies of the book and give it out to their employees. Former Presidents Barak Obama, George Bush and Bill Clinton received the book and all praised it. It was also given to the United Nations Secretary General and to French President Emmanuel Macron.

If Peres were alive today and was interviewed about the book, what do you think the takeaway quote would be?

“He would have said: ‘The book is behind us now. It’s in the past. Let’s talk about the next project; the future,'” Frish and Kornhauser answer almost simultaneously.