|

إستماع

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This article has been first published in the WSJ in 2011, but its content and message ring true today as it was then, especially with the demise of Bashar al Asad’s regime in Syria and the confusion and loss it has brought onto the Christians of Lebanon who supported such a dictator. Few people have had the temerity and the vision to foresee that as a human being, let alone as a Christian) one cannot support the rule of a tyrant against his own people, and the horrors of the civil war of Syria and its jails are a living evidence of this principle.

*

Syrian dictator Bashar Assad has now killed nearly 3,000 people and detained 70,000 in suppressing his country’s opposition movement. This is a crisis not just for Syria and the region, but for humanity and peoples of all faiths, and the Maronite Church in Lebanon has taken notice. Lebanon’s largest Christian body has long supported independence from dictatorship and military occupation, and allies itself with the present struggle of Arab youths against Arab tyrants, a struggle that began with Lebanon’s 2005 Cedar Revolution.

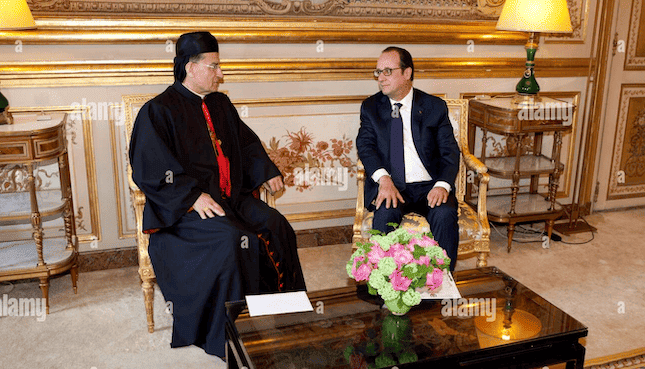

But Patriarch Beshara Rai, the Maronite Church’s current head, did an about-face on these core beliefs recently. During a visit to France last week, the Patriarch urged the international community to give Syria’s dictator an opportunity to reform. Calling Assad “open-minded,” the Patriarch said that “the poor man cannot work miracles.” “What we are asking of the international community and France is not to rush into resolutions that strive to change regimes,” he said.

With just a few words, Patriarch Rai has unraveled the struggles of millions of Maronites, sullied the memories of hundreds of thousands of Maronite martyrs against Syria, and crushed the hopes of many Lebanese. Assad is a dictator of the same lineage that oppressed Lebanon for 30 years. Today he fighting his own people with planes, tanks and artillery. Despite Patriarch Rai’s remarks, Assad has no friend in Lebanon’s Maronites.

Some may have forgotten the history of Syrian violence against Lebanon’s Christians. I have not. Growing up in war-torn Lebanon in the 1970s and ’80s, I knew nothing but Syrian onslaughts. During my youth, we were constantly running away from the shelling, bombing, booby-trapped cars and assassinations that the Syrian Army was perpetrating in Lebanon against the Christian population.

Syria’s violence is not perpetrated purely on religious grounds. No “Masada syndrome,” in other words, afflicts the fears of Lebanon’s Christians. Syria is an equal-opportunity butcher of all Lebanese who dare raise their voices to proclaim the independence of the Land of the Cedars.

But Syria’s leaders target Christians specifically. Christians are the first to be persecuted whenever there are rumblings of opposition to the regime. In 1978, I survived the 100 Days’ war in Ashrafieh, a Christian district of Beirut. Just as is the case today in Homs and Hama in the Syrian hinterland, Ashrafieh was encircled, deprived of food and water, and pounded with heavy machine guns, artillery and tanks. Many of my young friends died in such battles.

A few years later, in 1981, the Syrian Army besieged Zahle, a Christian stronghold in the Bekaa Valley. Zahle’s population was deprived of water and basic supplies, and the Syrian Army attacked the city’s defenders with full force. Many of my friends lost their lives that summer defending their ancestral land and their right to freedom. In 1982, the Syrian Army assassinated a newly elected Christian President of Lebanon, without any hint of regret, accountability or remorse. For Syria, it was business as usual.

Fast-forward to 2005, when Syrian-occupied Lebanon saw a series of assassinations, among them the killing of Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. A scare campaign in the Christian neighborhoods followed, in the form of random bombings and nightly explosions. What was Syria’s message? We can kill a Sunni leader, but if the Christians call for our withdrawal from Lebanon, your fate will be darker than at the hand of your Sunni fellow Lebanese.

That message was opposed fervently by the leaders of the Cedar Revolution, Christians and Muslims alike, who banded together in the wake of Hariri’s assassination. It was fought with equal fervor by Patriarch Nasrallah Sfeir, the head of the Maronite Church at the time. Since 2000, Patriarch Sfeir had called for the withdrawal of the Syrian Army from Lebanon, and for Christian-Muslim unity in Lebanon. During his tenure, he spearheaded a movement that culminated with the exit of the Syrian Army after 30 years of occupation—30 years of spreading corruption, destroying Lebanon’s social fabric and reducing the majority of its political class to mere vassals.

Maronite leaders have stood up for Syria, too. On May 29, 1945, France bombed Damascus and tried to arrest its democratically elected leaders. That day Prime Minister Faris al-Khoury, a Christian, was at the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco, presenting Syria’s claim for independence from the French Mandate. It was left to Maronite Patriarch Anthony Peter Arida to oppose the brutal attacks, decrying France’s barbaric assault against civilians. Patriarch Arida’s speech that day was hailed in the Al Omari Mosque in Damascus by Sunni worshipers, who had no other voice to defend them but the patriarch’s.

The Maronite Church is not a bastion of democracy. But the church has long been an advocate for an independent Lebanon, free from the shackles of foreign powers—whether Turkish, French or Syrian. For decades the church has been in synch with Arab nationalists who yearn to be free of dictatorship and military occupation.

So when Patriarch Rai says that the international community should not oppose Bashar Assad’s slaughter, Maronites around the world know better. Lebanese Christians’ fight against illegal militias, vassal politicians and rogue heads of state has only begun.

—Mr. Souaid is an independent asset manager and member of the New York State Bar Association.

(First published on Shaffaf on Sep 23, 2011)