On a visit to Paris to mark the 40th anniversary of the discovery of the HIV virus, the former chief medical advisor to seven US presidents looks back at the two great battles of his life: AIDS and Covid-19.

The whole world knows Anthony Fauci. He was the director of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), from 1984 to 2022, and served as chief public medical adviser to seven US presidents, from Ronald Reagan to Joe Biden. But it was his role during the Covid-19 crisis, sometimes contradicting his boss Donald Trump, that made him famous. During a visit to Paris for a conference on the 40th anniversary of the discovery of the HIV virus, which was held at the Institut Pasteur between November 29 and December 1, the recently retired 82-year-old spoke with Le Monde about the two pandemics that marked his life.

What has AIDS changed in our approach to infectious diseases?

There are many areas. In public health, it changed the appreciation of the negative role of stigma in diseases. In the very first years of HIV, we realized how much of a negative impact that stigma has on people. But, I would say there are many, many areas where HIV has, I believe, helped as a scientific enterprise, both infectious diseases in general, virology in particular, antiviral drugs in particular, and the development of a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of the immune system. Because it was such an extraordinary disease that throughout the world – here at the Pasteur, in my institution, the NIH – we poured in an amazing amount of money.

The virus was first discovered here [in France]in 1983. Then in 1986, we had the first drug tested, azidothymidine. And then for the next few years, until 1996, we had a couple of different drugs. We came to the conclusion, which was correct, that a combination of multiple different drugs can actually durably suppress HIV to the point of having somebody essentially live almost a normal lifespan. So that’s a big lesson in infectious diseases that whenever you have a goal, a mandate to apply your scientific capabilities, you can accomplish almost anything.

AIDS also saw the emergence of patients’ organizations on the health scene.

Yeah. One of the lessons is the importance of embracing the input from the communities who are either afflicted with the disease or are at risk from the disease. They didn’t have time for very rigid restriction criteria to get into a clinical trial. So the activists realize that and they try to gain the attention of both the scientific community and the regulatory authorities. And at first, certainly in the United States, the scientific community didn’t want to have anything to do with the activists. So they became very confrontational, theatrical, iconoclastic, until we – particularly me – paid attention to them. And when I listened to what they were saying, it became clear that they were absolutely correct in their concern. And if I were in their shoes, I would have done everything that they did. So that was when the scientific and regulatory community realized that even though they’re not scientists, they have a lot of important information and important perspectives to bring into the discussion of the design of clinical trials, on the importance of flexibility in the regulatory approach towards medications. It was a transforming lesson that has been applied now way beyond HIV, to a number of diseases.

And, on a personal level, what has this disease changed?

It changed my whole life. In 1981, even before we knew what it was, I saw that this was almost certainly an infection, almost certainly a virus, it was destroying the immune system. So I put aside everything else that I was doing, I changed the direction of my career. I started the first HIV group at the NIH in the fall and summer of 1981. In the dark. All of my patients were dying. I had no idea what to do. We were putting Band-Aids on hemorrhages. And that was the way it was from 1981 for me to 1987, when the first drug, AZT, slowed down the progression. And then finally, after nine years, when we developed the triple combination, then everything changed.

In 2020, you faced a new pandemic, Covid-19, as an adviser to the US president. In this battle, what were your greatest successes and failures?

In scientific terms, it was a resounding success. Normally from the time you identify a pathogen to the time you get a vaccine that’s going into the arms of people and effective and safe, it usually takes seven to 10 years. We did it in 11 months, which is completely unprecedented in the history of vaccinology. It’s also the result of a long-term investment in basic and clinical research. The work we did with HIV on structure-based design of antivirals has us quickly develop Paxlovid. The work on monoclonal antibodies that we did in so many other diseases allowed us to quickly get monoclonal antibodies for prevention and treatment of Covid. So the scientific part was absolutely elegant and successful.

Where we failed – not completely, but we could have done better – was in public health. In the United States, we had a real problem because we had multiple disagreements. The states wanted to do it one way. We had a political situation where the president refused to recognize the seriousness of the situation. We had people who were charlatans talking about drugs that didn’t work and getting people to not believe in science. It is estimated that the people who made a decision not to get vaccinated because of ideological political reasons probably accounted for about 200,000 avoidable deaths. That’s terrible.

Is this enough to explain the terrible death toll of over 1.1 million in the United States?

Officially 1.14 million, but it was probably more than that. One of the main reasons was the anti-vax. The other was the health disparities in our country. We have a very diverse country and the accessibility to health care is not like in France and in the European countries. Not all minority populations have as good access as someone who is in a higher socioeconomic status. But I think one of the most important reasons is the political divisiveness in our country. It is just extraordinary that if you look at the states – Florida, Texas, Alabama, Mississippi – the states that are Republican states have a higher death rate than the states that are Democratic, because they don’t want vaccines, masks, or public health things. By ideology, they don’t want to be told to do anything by authority. So it’s really an anti-science. I know there’s a little bit of that in France, but it’s very powerful in the United States.

The American health crisis didn’t start with Covid-19. Life expectancy, already low, has been falling steadily for the past five years. How can we explain this historic turnaround?

Firstly, we are an aging country, which increases the risk of life-threatening illnesses. Number two, the rate of obesity in the United States. More than 35% of the American public is obese. We also have a very serious opioid problem in the United States. It’s one of the leading causes of death in the United States. Then you look at gun violence, which is another thing. If you put together old age, obesity, opioids, and gun violence, it’s no wonder that you have people who are dying at a time when they shouldn’t be dying.

You’ve served both Democratic and Republican administrations. But today, Donald Trump’s fans hate you. How do you explain this dislike?

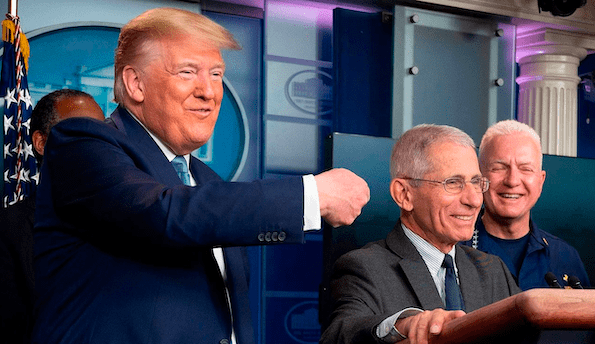

In my 54 years at the NIH and my almost 40 years as the director of the Infectious Disease Institute, I have had the pleasure and privilege of serving seven presidents, Democratic and Republican. I have always been respected for being honest and apolitical. I’m not a Democrat. I’m not a Republican. I stay out of politics. We only do science. What I had to do during the Trump administration was something that I did not like. I had to publicly disagree with the president of the United States. People who are Trump followers who hate me think I did it because I wanted to undermine the president. That’s the last thing I wanted to do, because I have a great deal of respect for the office.

But when he gets up in front of the camera and says the virus is going to disappear like magic, or when he gets up and says hydroxychloroquine is the answer, I’m sorry, I disagree with the president. I never disrespected him. I never criticized him. I said my responsibility as a scientist is not to a president. It’s not to a political party. It’s to the people of the United States and indirectly to the people of the world. Because I know people in France were listening to what I was saying, and I felt I had a moral responsibility to be perfectly honest with the people and say, no, it’s not going to disappear like magic. You’ve got to take precautions. You should get vaccinated. You should wear a mask. You should be careful. You should separate and social. It wasn’t against Trump. I was just trying to give the truth to the American people.

Did you consider throwing in the towel?

No. I am driven completely by my responsibility to the American public. I felt if I quit and walked away from it, there would be no one there who would be pushing back to try and make sure that we told the truth. So even though things got really tough at the end, as we got to the end of the year when, you know, people were saying, fire Fauci, throw him in jail and cut his head off, I felt I had to stick it out.

Were you scared?

There have been very credible threats on my life. People who were arrested with guns who were trying to come at me. That’s the reason why I have federal marshals with me all the time. It’s very disruptive of your life to have, wherever you go, have federal marshals with you all the time. But that’s part of the job.

The origin of the epidemic remains a matter of debate. Will we ever know whether it’s a zoonosis or a lab leak?

I don’t think we will. And the more there are these conspiracy type of approaches that you read in the far-right media, the less we’ll know. I think we need to keep a completely open mind. It could be one or it could be the other. I will totally accept the definitive evidence. Today, what evolutionary virologists say is that the evidence right now strongly suggests a natural occurrence. The animals were in the market. If you look at the evidence for a lab leak, I don’t see any credible evidence. There’s a very strong anti-China sentiment in the United States, which is, you know, unfortunate because it’s an important country, but particularly on the far right, there’s a very strong anti-China approach. And if you continue to be hostile to the Chinese, we’re never going to find out where it came from because we need the cooperation of the Chinese to figure out what went on there. I don’t think we’ll find that out if we continue to be hostile towards each other.

Some progressives also criticize you for funding gain-of-function experiments in the US and China. Are you convinced that the benefit/risk ratio of such genetic modifications of viruses has always been positive?

You’ve got to be careful of what your definition of gain-of-function is. If you look at the viruses that were studied in China with NIH grants, anybody who knows anything in virology will tell you that those viruses are so far removed from SARS-CoV-2, that it’s molecularly impossible for those viruses to have turned into SARS-CoV-2. When I say gain-of-function, it’s not only for Covid. I think people don’t understand what gain-of-function is. So, for example, there is a phenomenal amount of gain-of-function going on every day for the good of science here in Pasteur. As we speak, there’s gain-of-function work going on. That’s how you make recombinant insulin. Do you want to stop that?

Making a pathogen more infectious is another matter altogether, and a risky one at that…

Yes, and it should only be done rarely, when the final information deserves it, and if the people doing it are highly qualified, framed by very strict regulations. But we need it, for example, to study drug resistance and understand its molecular mechanisms.

Behind these experiments lies the fight against bioterrorism. With the new genome modification tools now much more accessible, aren’t you worried about the spread of biological weapons?

Whenever you can modify a pathogen, there’s always a risk that the wrong people in the wrong hands would do something that would be nefarious. That’s the reason why you’ve got to have good regulations and good controls, you. In 1975, the Asilomar conference, when recombinant DNA technology, some of which was discovered right here at the Pasteur, became available, everybody was worried. A group of scientists from all over the world laid some ground rules about what should and should not be done. And that has held true very well for almost 50 years. So it’s kind of a race between the people who could modify a virus and make it a weapon and the people who are trying to find defenses. And if you shut down the people who are trying to find the defenses… Remember, in the United States, the United States government can only regulate things that they fund.

We were talking about Trump. If he were to return to the White House, what advice would you give your successor?

(Laughs). Stick with the science!