Iraqis find themselves under censorship and tyranny of Islamist Iran

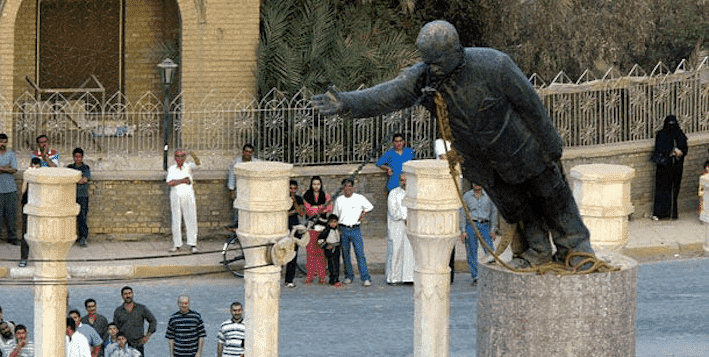

There is one country in the world that celebrates the American war to topple Saddam Hussain: Iraq. Most Iraqis still observe April 9 as Liberation Day, which marks when U.S. troops entered Baghdad and pulled down Saddam Hussein’s statue in Firdos Square, thus ending forty years of tyranny. Twenty years ago, I called this “my first day of freedom.”

In the early 1980s, Saddam’s tyranny forced my family to relocate from Iraq to Lebanon, where I was educated and began working as a journalist not long before Saddam’s downfall. In my circle of Iraqi family and friends, counting around 75 adults, not one of them opposed the war then or regrets it now. Their opinions are not unusual. Yet celebrating the fall of the Baathist regime does not necessarily entail gratitude to America. In public statements on Liberation Day, Iraqi leaders tend to erase the United States from the tale of liberation, as if the invasion happened of its own accord.

This silence reflects the influence of Iran, which deters most Iraqis outside the Kurdish region from publicly acknowledging any debt to America. Also unwelcome are reminders that Tehran opposed the invasion despite its bitter hatred of Saddam, who unleashed his chemical weapons on Iranian troops in the 1980s. Yet the clerical regime in Tehran judged Washington to be the greater threat. Few Iraqis felt that way. Even those who harbored pro-Iran sympathies often broke ranks and cheered for the war.

Iraq today is far from being the liberal democracy I hoped for when I relocated from Beirut to Baghdad the week after Saddam’s statue came down. With help from friends, I launched a magazine called the Baghdad Bulletin. We believed democracy was coming and we were determined to set up the fourth estate. But the magazine folded after one of our reporters was shot dead in the summer of 2003. It was obvious the United States had not thought of a plan on how to maintain order.

But saying that Iraq’s problem was an American failure is an overly simple view that presents the matter as an American choice alone, denying agency to Iraqis and, no less important, the regime in Iran.

Despite opposing the war, Tehran moved swiftly to infiltrate Iraq’s new government. With the aid of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Tehran armed, trained, and equipped Shiite insurgents who bled U.S. troops throughout the occupation. To be sure, Sunni extremists proved more lethal. Yet Gen. Joseph Dunford, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, testified in 2015 that Iran was ultimately responsible for the death of “about 500” U.S. troops out of 3,481 killed in action.

By the end of 2008, a “surge” of American troops, working together with hundreds of thousands of Iraqis in the country’s new security forces, had crushed both the Sunni and Shiite insurgencies. This created an interval of stability during which Iraqis would have a meaningful opportunity to build a democratic post-Saddam political order.

Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, a member of the country’s Shi’ite majority, had an opportunity to build a national following that transcended sectarian differences.

During the surge, Maliki had shown the Sunnis and Kurds that he could put national interests ahead of sectarian ones by facing down Shiite insurgents. Iraq’s rapidly growing oil revenue—which soon dwarfed Iran’s—also strengthened Maliki’s hand. He could also draw on the religious authority of the ayatollahs in Najaf, the capital of Shiite Islam, who favored sectarian peace over Tehran’s drive for Shiite hegemony.

Instead, when he faced challenges, Maliki quickly turned to stoking the sectarianism of his Shiite base. Iraqis who resisted the siren call of sectarianism understood Maliki would never be the founding father of a new Iraq, so in the 2010 elections they voted for Eyad Allawi, whose bloc edged out Maliki’s 91 seats to 89. Yet the latter twisted the terms of the constitution to claim he should be allowed to form a new government.

Stunningly, the White House sided with Maliki. On December 18, 2011, the U.S. completed its withdrawal from Iraq. The next day, Maliki tried to arrest Sunni Vice President Tariq al-Hashimi on bogus terrorism charges. Hashimi received a tip ahead of time and slipped away, but Maliki’s endless instigation against Sunnis proceeded to wreck any hope of stability. This seething resentment helped give rise to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which would force Obama to send American troops back in.

Maliki increasingly aligned himself with Iran, which was more than ready to capitalize first on the U.S. withdrawal and then on the chaos created by ISIS. Maliki eventually became so toxic that the White House helped push him out, but the damage was done. Iran would remain the dominant player in Baghdad.

The Iraqis I know have never conceded their independence to Iran. In 2019, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis demonstrated against the government’s corruption and subordination to Tehran. Activists burnt down the Iranian consulate in Najaf. Across Iraq, they have been torching posters of Iranian leaders. In July 2020, I lost my dear friend Hisham Al-Hashimi, who had outed Iranian money laundering networks in Iraq. Hisham was assassinated in Baghdad.

To many Americans, Iraq has been a bad dream. To many Iraqis, toppling Saddam was just the beginning. Today, Iraqis – like their Iranian neighbors – are fighting against the tyranny of the Islamic Republic of Iran. America is out but should still stand on the right side of history, the side of Iraqis seeking freedom. In twenty years from now, I hope to write my third article on Iraq, one on the story of how it became free and democratic.