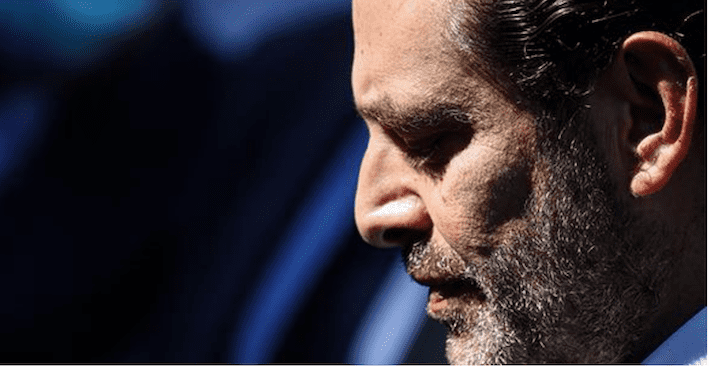

Saad al-Hariri may not run in Lebanon’s next elections, but writing him off may be hasty.

The principle reasons are not difficult to guess. Hariri has lost two of the longstanding pillars of his family’s political power in recent years—money and Saudi backing. The first was brought about by the disastrous management and ultimate bankruptcy of the Saudi Oger company established by his father, Rafiq al-Hariri, which Saad owned; the second was the result of Hariri’s fraught relationship with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and a Saudi perception that Hariri has not pushed back hard enough against Hezbollah. Hariri’s last-ditch attempt to ward away political irrelevance was his months-long effort to form a government, which ended in failure.

These days, Hariri is spending much of his time in Abu Dhabi. The story is that the United Arab Emirates has asked him to withdraw from politics, and instead focus on ameliorating his financial affairs. Some have suggested that the UAE is keener to bolster Saad’s older brother Bahaa, who has been more active in Lebanon lately.

While the tendency today is to assume that Saad al-Hariri is finished politically, it’s best not to be hasty. If Michel Aoun and Samir Geagea could survive their wholehearted destruction of Lebanese Christian society in 1990, and are still earnestly hailed by their followers and others as communal champions, it shows that the Lebanese are willing to resurrect just about anyone when the conditions are right.

However, it’s certainly true that Hariri is at a crossroads in his political journey, and without devising a clear way out of his predicament he may become superfluous. Recall what the Sunni cleric Ahmad al-Assir said when Hariri had left Lebanon after his government was brought down by Hezbollah and its allies in January 2011. Assir criticized Hariri, saying a leader should never abandon his partisans in the midst of a battle. The comment must have stung, but the reality is that Hariri’s absence from Lebanon between 2011 and 2016 was disastrous for his political career, because it showed that the country could function, for good or bad, without him.

Half of politics is about being where things happen, or preventing things from happening when one is not there. Hariri tried to make things happen in 2016 when he thought he could conclude a grand bargain with Michel Aoun and Hezbollah. He would support Aoun’s presidential bid, take a flexible position on Hezbollah, and as prime minister rebuild his patronage networks with new partners. This was a grave mistake as Hariri made three errors: He alienated his allies, alarmed by his opening to Aoun and his son in law Gebran Bassil. He undermined his own credibility with supporters, who felt his return was motivated mainly by a desire to reverse his financial setbacks. And he showed Aoun and Hezbollah that he needed them to be in power, which they repeatedly exploited to squeeze him.

Since October 2019, when Hariri resigned as prime minister in the midst of popular protests, his focus has been on political survival. At the time, he thought that after stepping down he would be able to form a new cabinet on his terms. This plan was torpedoed by the Lebanese Forces, who announced they would not designate Hariri again for the prime minister’s post. The message was widely viewed as an indirect Saudi thumbs down for Hariri, given the close relationship between the Lebanese Forces and the leadership in Riyadh.

Hariri tried a second time, starting in October 2020, after Mustapha Adib had failed to form a government in the context of the French initiative. His wager was that Hezbollah would agree to a Sunni-Shia partnership with him as the basis for a new consensus. This, he felt, would narrow Aoun’s and Bassil’s margin of maneuver and allow him to bring in a government in which the president and his son in law would have to accept whatever Hariri and Hezbollah agreed between themselves. He miscalculated, however, in imagining that Hezbollah would give him precedence over Aoun. For Hezbollah, choosing between Sunnis and Christians isn’t a zero-sum game.

Aoun’s refusal to make concessions that might have brought Hariri a measure of Saudi approval signaled the end. If no agreement was possible between the president and prime minister-elect, then Hariri was dispensable. He was out of options and had no choice but to approve of Najib Mikati as prime minister—if only to retain credibility with the French, whose plan he was purportedly trying to advance. That was the beginning of his eclipse. The closing of the Daily Star newspaper, regardless of whether it was tied to Saad’s political fortunes or not, was symbolic. By discontinuing a publication that could transmit the former prime minister’s perspective to Western audiences, particularly foreign embassies in Beirut, he seemed to be admitting there was no longer a need to do so.

Hariri’s political enemies, particularly Aoun and Bassil, might rejoice. However, it’s worth remembering that in the perpetual balancing act that is the Lebanese sectarian system, killing rivals politically is rarely an intelligent thing to do. The enemy of today is invariably the potential ally of tomorrow. Does it really benefit the president and his son in law to leave themselves with no strong counterparts in dealing with Hezbollah? Do both men seriously think that the Christians alone, without Sunni assistance, can effectively oppose the party if its paramount interests or choices go against theirs?

Saad al-Hariri may yet run in elections, though the strong possibility they may not happen is surely something he has factored into his decision. Whichever way Hariri leans, it’s obvious he’s preparing for a long period in the political wilderness. Lebanon may not be the worse for it, but nor is it reassuring that Sunnis should feel that their leaders alone are the ones being eliminated from the political landscape.