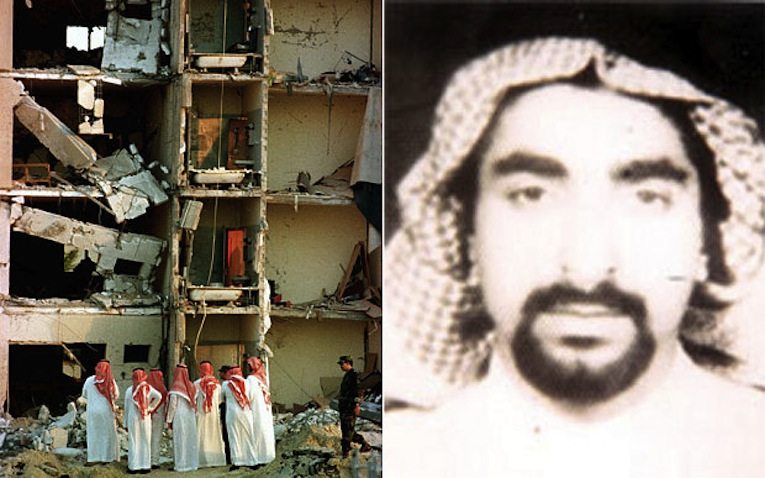

A closer look at how an Iranian-linked Hezbollah chief bombed the Khobar Towers and walked free — until last month.

Two weeks ago, according to several media reports, Ahmed al-Mughassil, the military chief of Saudi Hezbollah (Hezbollah al-Hijaz) and the principal architect of the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing, was apprehended in Beirut — where it was believed he lived under Lebanese Hezbollah protection — and was transferred to the custody of Saudi Arabia. A physically small man, standing at five feet four inches and weighing 145 pounds, Mughassil is accused of orchestrating and then personally executing one of the most spectacular terrorist attacks carried out by Iran and its proxies against the United States.

The circumstances of Mughassil’s capture are still unknown, but the timing raises multiple questions. How did a man who evaded capture for almost 20 years suddenly get caught? And what does it mean that the arrest comes against the background of the Iran nuclear deal and in the context of rising tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia and between their respective allies in Lebanon?

Officials in Beirut, Riyadh, and Washington have yet to confirm Mughassil’s capture, but it is no secret that both Saudi and American investigators have been keen to apprehend him for years. Mughassil was indicted in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia for the bombing, and the U.S. State Department’s Rewards for Justice Program offers $5 million for information leading to his capture.

Mughassil was known to Saudi authorities even before the Khobar bombing, which is why he fled Saudi Arabia in the 1990s and made his way to Beirut. It was in Beirut that, around 1993, Mughassil set in motion the plotting and surveillance that would lead to the attack on U.S. and coalition forces stationed at Khobar Towers in 1996.

SURVEILLANCE

In 1993, the FBI would later conclude, Mughassil instructed a Saudi Hezbollah cell to initiate surveillance of Americans in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Hezbollah operatives spent three months casing American targets in Riyadh, passing their surveillance reports to Mughassil, who met with the operatives to debrief them personally. He then shared the reports with Iranian officials. In early 1994, Saudi Hezbollah expanded surveillance beyond Riyadh to the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. In late 1994, after extensive surveillance in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, several Saudi Hezbollah operatives specifically identified Khobar Towers, in the city of Khobar, as an important U.S. military location. Mughassil now focused on this target and quickly provided funds for the express purpose of finding a place where Saudi Hezbollah could store explosives in the Eastern Province.

As surveillance of Khobar Towers continued, Mughassil needed to ensure that he could smuggle the explosives for the operation from Lebanon, through Jordan, into Saudi Arabia. It was time for a test run, although the driver hired for the mission, Fadel al-Alawe, would be told it was the real thing. Only on his arrival back home did Alawe discover that Mughassil had been testing him.

Later that year, around October 1995, a man showed up at Alawe’s door in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province and handed him a map of the Khobar Towers complex. Mughassil wanted Alawe to check the map’s accuracy, the visitor informed him. When the man returned to retrieve the map a little while later, he left a small package weighing about a kilogram. Alawe knew better than to inspect the package, which he held on to until Mughassil called with instructions to deliver the package to yet another person.

Then, in late fall 1995 and again in late 1995 or early 1996, a Saudi Hezbollah operative returned to Beirut to confer with Mughassil about the Khobar plot. During the first of these meetings, he brought more surveillance reports to Mughassil and learned for the first time that Hezbollah would be attacking Khobar Towers with a tanker truck loaded with explosives and gasoline. At the second meeting, Mughassil began to lay out the operational roles of different cell members. He discussed the need to accumulate enough explosives to destroy a row of buildings and noted that “the attack was to serve Iran by driving the Americans out of the Gulf region,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice indictment.

In all likelihood, what enabled the Saudi Hezbollah cell members to successfully execute these surveillance efforts undetected was their prior training in Lebanon and Iran. But they also enjoyed close oversight and support during the operation from senior Lebanese Hezbollah and Iranian officials. During the cells’ surveillance activities, for example, Mughassil told one operative that he had received a phone call from a high-level Iranian government official inquiring about their progress. Later, according to the U.S. indictment, Mughassil further confided that “he had close ties to Iranian officials, who supplied him with money and gave him directions.” Indeed, Saudi information suggests that he “has strong family ties to Lebanese Hezbollah and has been in contact with the office of the Supreme Leader Khamenei.”

SAUDI STRATEGY

Briefed in Beirut, Mughassil traveled in January or February 1996 to Qatif, not far from Dhahran and Khobar Towers, where he instructed one of his operatives to find places to stockpile and hide explosives. Sites were apparently identified rather quickly, because sometime around February, a Saudi Hezbollah operative returned to Beirut at Mughassil’s direction and drove back to Saudi Arabia in a car stuffed with hidden explosives. When he arrived in Qatif, the operative delivered the car to an unknown man whose face was veiled.

Hezbollah suffered a serious operational setback the following month. Having passed Mughassil’s test run the previous June, Alawe was summoned back to Beirut in March 1996 and given the keys to another car stuffed with hidden explosives. Alawe drove the car through Syria and Jordan, arriving at the al-Haditha crossing point on the Jordanian-Saudi border on March 28. “But unlike his mysterious counterpart, who had been able to smuggle explosives across the border in his earlier run, Alawe was arrested on the spot when Saudi border guards inspecting his car discovered 38 kilograms. This, in turn, led to the arrests over three days in early April of the rest of the Saudi Hezbollah cell.

Suddenly, Mughassil found himself without his key operatives and facing the prospect that some elements of the operation might be compromised. Undeterred, however, he quickly found replacements for his four detained operatives and assumed a hands-on role to see the operation through.

Sometime in late April or early May, Mughassil returned to Saudi Arabia to personally assemble a new hit squad. Traveling on a false passport and under the cover of a pilgrim on hajj, he appeared unannounced at a Saudi Hezbollah member’s home in Qatif on May 1. Mughassil briefed his host on the Khobar Towers bomb plot and on the arrests of the four cell members and asked for his help in executing the attack. Mughassil must have assumed that his host would answer in the affirmative, because before leaving, Mughassil provided him with a forged Iranian passport that must have been prepared in advance and told him to “be ready for a call to action at any time.”

Three days after visiting the first Saudi Hezbollah operative, Mughassil knocked on the door of another Saudi Hezbollah operative and, after recruiting him to the operation and briefing him on the plan, left him a timing device to hide at his home. At least twice in the months leading up to the Khobar bombing, another Saudi Hezbollah cell member turned up at the recruited operative’s home seeking help hiding several 50-kilogram bags and paint cans filled with explosives at sites around Qatif. Then, with just about three weeks to go until the planned attack, Mughassil and an unnamed Lebanese Hezbollah operative moved into the recruited operative’s home in Qatif, where they assembled the bomb.

Meanwhile, the plot continued apace. Using stolen identification, the cell purchased a tanker truck from a Saudi car dealership for about 75,000 Saudi riyals, or some $20,000. The cell spent the two weeks leading up to the attack converting the tanker into a massive truck bomb at a farm in the Qatif area. Mughassil was part of the team at the farm, along with the rest of the Saudi Hezbollah cell and the Lebanese Hezbollah operative. The explosives were concealed within the gasoline tanker truck such that they would be unseen even if the truck was stopped and inspected. Had someone opened the hatch atop the tanker, he would have seen what appeared to be a tanker full of gasoline. In fact, the crew had secured a 50-gallon drum to the inside of the full 20,000-gallon tanker. Beneath the gasoline-filled drum, the rest of the tanker was filled with at least 5,000 pounds of plastic explosives. When detonated, the truck bomb would pack the punch of about 20,000 pounds of TNT.

With all the operational details attended to, several of the conspirators met at the Sayyeda Zeinab shrine in Damascus. The purpose of the meeting, held sometime around June 7-17, was to confer with the senior leadership of Saudi Hezbollah. The group’s leader presided over the meeting, reviewing details of the bombing plot and making clear to all that Mughassil was running the operation.

A week after the go-ahead meeting in Damascus, Mughassil and the members of his cell returned to Saudi Arabia and were ready to execute the attack. On the evening of the attack, they met at the farm in Qatif, about five miles from Khobar Towers, to review final preparations. Present at this meeting were only the members of the actual operational unit.

Two members of the Saudi Hezbollah cell left the farm first, shortly before 10 P.M. Driving a Datsun, the two pulled into the parking lot adjoining building 131 at Khobar Towers and parked in the far corner. Serving as scouts, they scanned the area for patrols or anything else that might disrupt their attack. A white Chevrolet Caprice sedan entered the lot next. The Caprice was borrowed from an acquaintance, who likely had no idea that his car would serve as the getaway for the perpetrators of a massive terrorist bombing. Seeing no problems, the scouts flashed the Datsun’s headlights, signaling the “all clear” for the final vehicle to enter the lot. On their signal, the truck bomb entered, driven by Mughassil himself with one other passenger. They backed up the truck to the fence in front of building 131, then jumped into the backseat of the waiting getaway car, which drove away, followed by the lookouts in the signal car.

Minutes later, the bomb exploded, leaving a crater 85 feet wide and 35 feet deep. The blast was the largest non-nuclear explosion then on record and could be felt 20 miles away across the causeway in Bahrain. Nineteen U.S. service personnel were killed, and almost 500 more people from at least seven countries were wounded.

Mughassil’s capture may well have been coincidental to the sectarian tensions rocking the region and to the pending nuclear deal with Iran. Or, as a longtime fugitive, Mughassil may have slipped into routines that enabled authorities to identify and arrest him. It is telling, however, that the capture comes against the backdrop of the nuclear deal and Iranian and Saudi competition for influence in the region in general and in Lebanon in particular — and just as Lebanon descends into chaos. Whatever the circumstances, the apprehension of the man who orchestrated such a massive attack would be no small matter. Not only do the families of the victims deserve justice, but the Farsi-speaking Mughassil is uniquely positioned to shed much-needed light on the covert activities of Iranian operatives and their agents and proxies in the region.

******************************

Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler Fellow and director of the Stein Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute. This article was originally published on the Foreign Affairs website (https://www.foreignaffairs.