Although not much can be done about disarming Hezbollah at the moment, any serious Western policy will need to focus on sanctioning the group’s domestic political enablers while engaging and protecting its Shia opponents.

Lebanon as a state entity all but collapsed some time ago. It’s not official yet, and no one seems ready to declare it a failed state, but the government institutions are practically broken and nonfunctional. The economic crisis that has led to the depreciation of the lira by more than ninety percent meant that the salaries of public servants are not even enough for transportation to and from work. Many vital public institutions, such as the Lebanese University, the Electricity Company, service ministries and municipalities, are barely functioning. The crisis had caused a serious exodus from civil service across the board. The core of the state institutions—its public service—is gone.

Lebanon has never seen a collapse of this magnitude—even during the civil war. And the dreadful part is that this is not the worst scenario. More deterioration of the economy, depreciation of the lira, and a serious social explosion are on the horizon. Stopping this collapse and starting the long and thorny road to rehabilitate the Lebanese state requires more than reforms. Yes, reforms to the economy, banking, fiscal, and security systems are vital; however, we all know by now that none of this will happen as long as an armed Hezbollah is overseeing this decline.

This sudden and severe collapse did not happen because of corruption alone, and it will not be completely resolved by economic and financial reforms. Corruption and a weak state apparatus are the core of Hezbollah’s policy. Reforming certain sectors, electing a president, or forming another government that looks a little better than the last, all are important steps to maintain a sense of agency; nevertheless, the clash is not between two Lebanese political parties. It is a clash between a kidnapper and a hostage

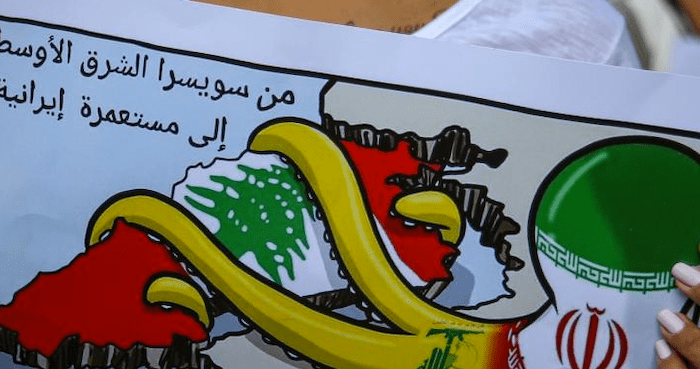

It is as a hostage that Iran views Lebanon—there’s no need to have a socio-economic policy for Lebanon, or for Iraq or Syria for that matter. On the contrary, a prosperous Lebanon means a stronger state, and that’s not in the interest of Iran and Hezbollah—a hostage needs to stay weak and frightened. What matters is how to maintain and strengthen Iran’s grip on these countries, whether their citizens stay, leave, or die trying. In this context, the institutional tools that Lebanon is using to show the world that it is still functioning as a democracy have been rendered worthless by Hezbollah’s arms, or threat of armed force. In the formula of ballots vs. bullets, the latter is always louder and more heard.

The Lebanese people decided to challenge this status quo on October 17, 2019, when people from all sects and regions took to the streets to say no to corruption, the political system, and for the first time, to Hezbollah and Iran. The status quo didn’t change much, and the protests were hit by COVID and then the Beirut Port blast, but they did manage to achieve a number of important outcomes, such as the removal of Saad Hariri from the political scene. Most importantly, the protests exposed the true face of Hezbollah: the protector of the system, and the guardian of corruption, violence and injustice. Eventually, this translated into Hezbollah’s loss of its parliamentary majority in May 2022.

The group’s popularity took a dramatic hit, and criticism against their practices and policies intensified on both social media and in the streets. However, between seeking the people’s love and instilling fear, Hezbollah chose to instigate fear. The group threatened, attacked, and harassed activists and constituents who expressed discontent. Then they killed Lokman Slim—and the wall of fear went up immediately, and a sense of control was reestablished.

The Challenges for Hezbollah

Hezbollah’s goal today is to maintain their control and regain the power they lost in the parliamentary elections by imposing their choice for the next president and their vision for the next government. They will continue to prohibit attempts to reform institutions and will become the party with the best access to hard currency in Lebanon. They will use all tools possible to establish long-term control over Lebanon, even if this means a change of the constitution or the elimination of the Taif Agreement. This will be the last nail in the coffin for Lebanon as we know it.

For Hezbollah, a new constitution for Lebanon could be the only guarantee for Iran’s power and entrenchment. And further deterioration of the state institutions and the economy could pave the way for the group and its allies to call for this scenario.

But this phase in Lebanon’s chapter, and Hezbollah’s strategy to deal with it, comes with many risks and challenges. First, the Lebanese realize today that Hezbollah’s weapons are directed at the Lebanese people. This has transformed them from being the “resistance” and “liberators” of 1982 and 2000 to the new occupiers. This shift in perception will lead to a serious change in the dynamics between them and the Lebanese people, mainly the Shia community. Without the embrace of the Shia, Hezbollah cannot thrive.

Second, Hezbollah’s popularity could erode further, and this will continue to influence the upcoming municipal and future parliamentary elections. They could continue losing voters and allies, and eventually, the risk of losing decision-making power will be real.

Three, it has become a liability to ally with Hezbollah. Its current allies either lost the elections, got sanctioned, or both. And in return, Hezbollah can no longer guarantee presidencies, ministries, or business deals. Michel Aoun left the presidential palace, and his son-in-law Gebran Bassil has not replaced him.

Four, the group understands that they can threaten with their arms without using their arms, but not indefinitely. They know that once they use them, they lose them. Iran is no longer in a good place to restock Hezbollah with money and weapons the way they used to, and Hezbollah had to come up with alternatives. The drug and smuggling business to which they resorted in the past also harmed their image and transformed the “resistance” into the biggest drug cartel in Lebanon and possibly the region.

Five, the maritime deal Lebanon signed with Israel in October 2022 was approved by Hezbollah in order to avoid a conflict with Israel. But this had implications for the group’s rhetoric: Hezbollah had to acknowledge the existence of an enemy state and accept a diplomatic deal with it. The image of resistance took a hard hit.

These challenges are not going to force Hezbollah to change its policy or its allegiance to Iran. As long as it has the weapons, the strength and power over Lebanon, and most importantly, works with the absence of international concern over Lebanon, the group and its sponsors in Tehran will probably find a way to walk the line between power and popularity.

Opportunities and Recommendations

The Lebanese, Syrians, and Iraqis look today at Iran and feel a sense of hope because they know a change in Iran means change in their own countries. This might take a long time, but there are ways to make Hezbollah more vulnerable in Lebanon. This requires a comprehensive policy towards Lebanon—between the United States, Europe (mainly France) and Saudi Arabia. It also needs to involve the Lebanese opposition groups—no policy has ever worked in Lebanon without active internal involvement. So far, the discussion on Lebanon is already underway among all these states, but it is still focused on the humanitarian program. A serious policy should hit Hezbollah’s three main pillars of power in Lebanon: the Shia community, the allies, and the weapons.

More sanctions on Hezbollah’s allies’ certainly help. But it is time for Europe—France in particular—to start issuing the sanctions they’ve been discussing since 2019. In addition, Hezbollah’s allies should not be allowed to visit the US or Europe or even have bank accounts and assets in any of these countries. It should be made very risky to ally with Hezbollah.

As for the Shia community, this is the perfect time to work directly with the Shia, listen more to the voices of discontent, and give political and material support to the new opposition among the Shia—mainly those with socio-economic visions. These also need protection and support—without protection, Hezbollah will kill them as they killed Lokman Slim and others.

The existence of large supplies of weapons is a different game altogether. No one can really target this arsenal without a war. Israel has been taking care of Iran’s weapons factories and facilities in Syria, but the ones in Lebanon have been stored underground since 2006. Some expired, but many still constitute a serious risk in the next war with Israel. There are two ways of dealing with these: either targeted attacks by Israel that would destroy weapons without killing civilians, or exposing the weapons facilities built under civilian infrastructure, such as schools and hospitals. The Lebanese people have no idea what’s under their homes and land, and they certainly do not want to risk anything anymore.

These pillars are already shaking—Hezbollah’s allies lost during the elections, Iran is facing its own challenges, and the Shia community has lost faith in Hezbollah. Now is the time to hit hard. Ultimately, the Iranian people might be the only hope left for the region, but as we wait, constraining Hezbollah in Lebanon could help. The alternative is alarming—a new Lebanon, with a new constitution that would guarantee Hezbollah’s power and control, with or without Iran.

Hanin Ghaddar is the Friedmann Fellow at The Washington Institute and author of Hezbollahland: Mapping Dahiya and Lebanon’s Shia Community. This article was originally published on the Hoover Institution website.