Watching the Ukraine conflict, Middle Eastern leaders see the Russian president has approached matters in the same way as they would.

Without wanting to fall into cultural determinism, the Ukraine conflict has highlighted the very different concepts of power and victory in Western countries and Russia. Not surprisingly, many Arab governments have been more adept at understanding the rationale and calculations of Russian President Vladimir Putin than have his Western critics.

When the Russians invaded Ukraine, and the Ukrainians fought back, successfully at first, the narrative appeared to have been written for a Hollywood movie. The underdog was defeating an evil aggressor, and a happy ending was at hand. In late April, at a meeting of defense ministers, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin remarked, “Ukraine clearly believes that it can win, and so does everyone here.” This statement came at around the time Austin declared that Russia was failing and that the United States wanted to see its military “weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.” President Joe Biden went even further, insisting that Putin “cannot remain in power.”

Today, things look quite different. Russian forces are making major gains in eastern Ukraine and Western economies are suffering from rising oil and gas prices, which are benefiting Russia. Biden, in an apparent bid to shift the blame, has declared that earlier this year Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky “didn’t want to hear” that Russia was about to invade his country. The implication was that, had Zelensky assessed the situation better, he might have taken a different course and spared Ukraine what it is enduring. That’s a far cry from Zelensky’s comparison with Winston Churchill during the early weeks of the conflict. Western countries are now skeptical about prospects that Ukraine will prevail, and increasingly divided over what to do. For all the talk of Putin’s madness, Russia is winning.

Certainly, Russians will suffer for a long time from Western sanctions. But from Putin’s perspective, that’s a price he’s willing to pay—and that he was always willing to pay if the alternative was a defeat in Ukraine. Time will tell if the Russians can hold onto eastern Ukraine, but for now Russia has consolidated its access to Crimea, has denied Ukraine its industrial heartland, has brought home to the West that a significant portion of Ukraine will probably remain under Moscow’s control, and has shown Ukrainians that there are real limits to how far the West will go in helping them to defend themselves.

From an Arab perspective, this may all look familiar. What Western countries regard as benchmarks of victory and defeat in war are often almost irrelevant in the Middle East. What constitutes victory is usually not so much an effective assertion of power, even if that is important, but survival against a stronger enemy. Hezbollah somehow managed to portray its war against Israel in 2006 as a “victory,” though it had achieved none of the classical criteria Western officials would have used to define victory. Similarly, Iran has been targeted by U.S. sanctions for decades, suffering terribly, but it has not altered its behavior. Indeed, it has doubled down and made major gains throughout the Middle East. To Iran’s leaders, victory is not just about defeating the other side, it’s about persisting in its ideological path.

Much the same applies to Russia against a stronger Western world. When Western leaders say Russians will feel the hurt from sanctions and turn against Putin, they seem to be living in a bubble. Certainly, the Russian president is not happy to see his society increasingly disgruntled. However, the only thing he will be watching for is whether this threatens his power. A similar attitude has been adopted by leaders in the Arab world—from Syria to Lebanon to Sudan to Egypt to Algeria—when ruling oligarchies have felt vulnerable. Western officials have democratic elections, but authoritarian systems in the Arab world and Russia can always manipulate outcomes, and resort to violence, if they momentarily lose their grip.

One thing Arab leaders will not have sympathized with is the Ukrainians’ inflexible reading of their options. There was a moment when Zelensky could have played the survival game, allowing himself room for maneuver. In February, French President Emmanuel Macron traveled to Moscow and Kiev to negotiate a solution for the brewing crisis. On the flight to Russia, Macron brought up the idea that Ukraine might consider an arrangement akin to “Finlandization” as a way out of the impasse. He was condemned for this. However, was Macron wrong? Finns look back on “Finlandization” with displeasure, recalling a time when their sovereignty was limited because of their country’s proximity to the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Yet Finland remained free, as well as a part of Western Europe.

As my former colleague Dmitri Trenin noted in an interview with Diwan, when he was asked about the possibility of Ukraine’s “Finlandization,” the country was facing a stark choice: “I would simply look at the real geopolitical and strategic situation of Ukraine. It has been made clear by none other than U.S. President Joe Biden that the United States will not defend Ukraine, even in the case of a major invasion and occupation.” In other words, if a stronger foe is about to pounce on you, making a deal to preserve what you have may sometimes be the best way to go.

Certainly, throughout the Middle East and North Africa, countries are well aware of the limits to their sovereignty, and frequently adapt to it. Lebanon has long been trapped in Syria’s shadow, and now Iran’s, and while this has been resisted by parts of the population at various times, it’s a reality with which most people have accepted to live. For a long time, Saudi Arabia had significant influence in Yemen, until Iran increased its own sway in the country. Today, Iran has leverage in Iraq and Syria, while Turkey controls a large swathe of northern Syria, which it may soon seek to expand. Similarly, Egypt has long had a say in Sudan.

The reality in the Middle East and North Africa is that the contours of sovereignty remain ambiguous and indistinct. This is far from ideal, but countries have had to adjust to this, if only to buy time until a more advantageous situation comes about. Had Ukraine delayed Russia’s invasion through diplomacy and bargaining over the Minsk Accords, it might have averted the onslaught and used this interregnum to reinforce itself. After the Lebanese civil war ended in 1990, Damascus imposed a series of agreements on Lebanon that were onerous. However, the situation shifted decisively in 2005, when widespread anti-Syrian protests in the aftermath of Rafiq al-Hariri’s assassination forced the Syrians to withdraw their army.

Defending principles such as sovereignty and freedom is understandable. Such principles are meaningful, but only if they can be defended. If they cannot, suicidal stubbornness in resisting is not always the optimal fallback position. Ukraine’s destruction may prompt many people to reconsider the narrative of heroic defiance during the invasion’s early weeks. Zelensky’s “Churchillian” speeches may begin to grate if the price to pay is Ukraine’s ruin, mass emigration, and economic impoverishment. History tends to admire those who avoid the passions of the moment for a more long-term grasp of what is in a country’s best interest.

The Arab states may be led by ruthless, failed autocrats, but these individuals have also been masters of survival. When it comes to imposing their writ, they have not been bothered by factors inhibiting their Western counterparts.

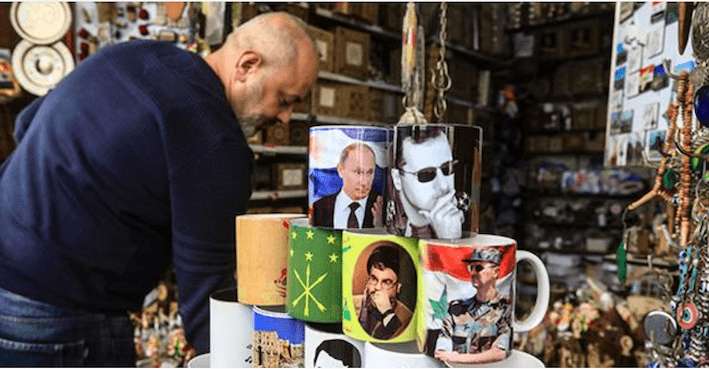

That is why they have been so reluctant to condemn the Russian president, whom they appear to have embraced as one of their own.