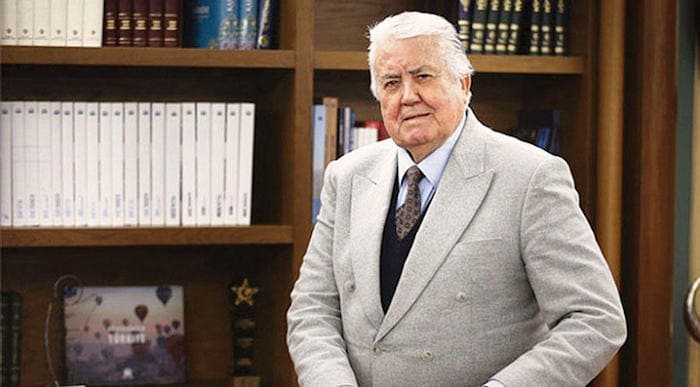

The Sumerologist Veysel Donbaz speaks languages almost no one speaks today: Sumerian, Hittite, and two dialects of Akkadian, which are Assyrian and Babylonian.

There are many dead languages which have been identified to this day, according to Donbaz. “The language must be a written one to be identified as a dead language,” he said.

Besides the archaic languages, Donbaz speaks contemporary languages like English and German. After retiring from the Tablet Archive at the Istanbul Archeology Museum as its head, the 78-year-old continued his studies in the field of cuneiform tablets and ancient languages. Speaking to state-run Anadolu Agency, he touched on the role of unspoken languages in unearthing history.

Born in the Bekilli district in the western province of Denizli, Donbaz completed his primary and secondary education in Istanbul and studied at the Sumerology Department of Ankara University’s Faculty of Languages, History and Geography. He graduated as the only student of the department and was appointed to the Istanbul Archaeology Museums right after.

Donbaz identifies himself most as a Sumerologist. He also says that he is an “Assyriologist” rather than an Asurologist, noting that “Assyriology includes Sumerianand Akkadian, of which Assyrian is a dialect.

Donbaz said the most important dialects of the Akkadian language, which is a member of the Sami language family, were Assyrian and Babylonian, and added: “Akkadian is a state. Sumerians carried the cuneiform tablets wherever they went since 3,500 B.C. or it is told that they discovered it. Around 2,800 B.C. it was possible to write all literary texts on the cuneiforms. It developed in 1,000 years.”

He said Sargon founded the Akkadian Empire in 24th century B.C. and literary documents were translated into Akkadian language.

“Some documents are in two languages. There are 75,000 tablets at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. We see these two-language documents there,” he added.

Donbaz said the Turkish language had more than 100 words from the Assyrians and Babylonians, but no word from the Sumerians.

“Almost all countries around us use a different alphabet,” he said.

In order to fully understand Sumerian and Akkadian, when one of these languages is learned, the other should also be learned, said Donbaz. “If you do not know another one, you cannot do anything. You will know the conceptual value of each syllable.”

Stating that a dead language means the language is no longer spoken, Donbaz said he has publications mostly in the Akkadian language.

Assyrian and Babylonian were two dialects of Akkadian, and the people of Assyria and Babylonia used Akkadian in international relations, according to him.

Speaking of the international activities of the Hittites, Donbaz said: “There are 38 known agreements. Among them 19 are in the Hittite language and 16 are both in Hittite and Akkadian languages. They wrote Hittite to the top, Akkadian to the bottom. They used cuneiform. The cuneiform has Sumerian ideograms. For example, gold, silver, tin and copper are used with an ideogram. The fabric sounds are used separately. None of these have names. They’ve got the same as the Sumerians.”

The effects of Akkadian on Turkish

Donbaz said any of these dead languages was difficult to verify, leading to many discussions among experts.

“There are many dead languages discovered so far. There must be a written source for a language to be accepted as a dead language,” he added.

Contrary to what is believed, Donbaz said that most Turkish words were not from Persian or Arabic but from the Akkadian language and that the name of seven months in Turkish are from Babylonian.

Modern Turkey founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk founded the Turkish History Association in 1936, opening 23 departments including the Hittite and Sumerianlanguages, as well as Hungarian and modern philology, he said.

“I made the inventory of 30,000 tablets out of 60,000. I also published more than 2,500 tablets. Most of these tablets are at the British Museum and some are in Turkey. Sumerians have a magnificent literature; they wrote thousands of documents,” he said.

Stating that some 25,000-30,000 tablets were found in Kültepe in the Central Anatolian province of Kayseri, Donbaz said they held a meeting there every two years.

There are nearly 1,500 Sumerologists in the world, 10 to 15 of whom are based in Turkey.

He also noted that he brought back 7,500 tablets from Germany to Turkey, which is the second important center in the world in terms of cuneiform tablets with a number of 50,000. “They were generally kept in palaces or temples,” he added.

Born in 1939 in Denizli, Donbaz graduated from Ankara University Faculty of History and Language’s Sumerian department in 1962.

He started working at the Istanbul Archaeology Museums and also worked as an English teacher. His articles and cartoons were published in many magazines as a freelance writer and cartoonist.

During his career, Donbaz also served in programs carried out by the Culture and Tourism Ministry and UNESCO conferences, while also participating in many international projects. He participated in panels and conferences abroad as a guest.

He played a role in the process of bringing 7,500 Boğazköy tablets to Turkey in 1987.

He also served as a guide for foreign diplomats visiting Turkey. In 2016, he published a book titled “Bin Kral Bin Anı, Bir Sümeroloğun Anıları” (A Thousand Kings, A Thousand Memories: Memories of a Sumerologist.”