Taiwan is not a new problem for practitioners of American foreign and defense policy. It has been a thorn in Washington’s side since 1949. But the Taiwan issue has become ever more vexing and it now presents the preeminent challenge due to the imperative to avoid a global nuclear conflagration. There are myriad other aspects of the problem to be understood: the economic, political, diplomatic, historical, and conventional military aspects of the issue are all addressed below. Now, there is the additional weighty question of what can be done today to prevent Taiwan from becoming a “second Ukraine.” To say this issue lacks easy answers would be a vast understatement. In this essay, I argue that wise and cautious diplomacy must prevail since I see no feasible military solutions.

The nuclear problem

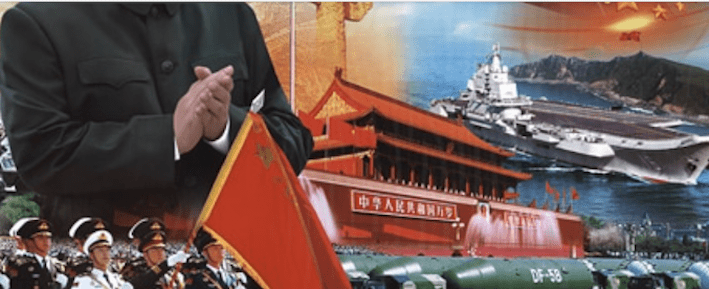

Above all, there is a significant danger of escalation to the nuclear level in any hypothetical US-China military conflict over Taiwan. For years, China’s nuclear deterrent was generally dismissed by Western strategists as both small and backward. But this is starting to change and Washington is now quite disturbed by China’s on-going nuclear buildup. There are quite a few troubling revelations about this buildup in the Pentagon’s November 2022 report on Chinese military power. It stated that China has now surpassed 400 operational warheads and that this number could reach 1,500 by 2035. New and large ICBM fields are reportedly being constructed in northwest China, while the China’s military (known as the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA) has ramped up its navy significantly, and is said to have begun “continuous deterrence patrols” with its new force of strategic submarines. Major new steps are expected for the Chinese long-range bombers force, as well. Finally, there are strong hints of accelerating Chinese development of both missile defenses and hypersonic weaponry—and even perhaps tactical nuclear weaponry as well.

Nobody can say what would happen if two nuclear powers entered into an intense war, because this has never occurred. Nuclear powers have engaged in skirmishes, but nothing beyond that threshold, fortunately.

But would the “nuclear taboo” hold in a Taiwan conflict? Maybe yes, but maybe not. Many Western strategists have suggested that Beijing could resort to nuclear first use if its conventional forces were losing (Colby, 2021).

The possibility of a Chinese resort to nuclear weapons is noted in the recent Pentagon Report on Chinese military power (US Department of Defense 2022). Indeed, a recent Taiwan wargame by a Washington, DC, think tank did see China’s employment of a nuclear warning shot (Katz and Insinna 2022).

The inverse scenario also seems quite plausible, however. In other words, it is possible that US conventional forces could be overwhelmed in a Chinese attack on Taiwan. In that case, an American President may see nuclear weapons as the only card to play against China or as retaliation for grave US losses, for example if one or more US carriers were to be sunk. In fact, a novel that portrays a US-China war over Taiwan in 2035, written by a very senior US retired Admiral, does include such a US resort to first use and a catastrophic “trade of cities” between the two superpowers that kills millions of innocents (Ackerman and Stavridis 2021). There are also increased risks of inadvertent nuclear escalation, since artificial intelligence is playing a larger and larger role in military operations for both sides—and also both sides can now threaten early warning systems and ballistic missile defenses. The threat of nuclear catastrophe is the most disturbing of the risks attendant to a Taiwan military conflict, but there are many other risks as well: economic, asymmetric, and historic—as well as problems with alliances, and military problems.

The economic problem

The economic disruption that would result from a US-China military conflict over Taiwan would also be devastating to both countries. Despite much rhetoric about “decoupling”—the effort to separate the US and Chinese economies and make them less interdependent—trade between the two countries continues to set records, reaching $760 billion in 2022 (Flatley 2023). Within this relationship, there are numerous synergies. For example, China is lacking in arable land and thus it makes sense for America’s more efficient farms to produce agricultural products for China. Consequently, America’s Midwestern bread basket has benefited substantially from blossoming US-China trade over the last few decades.

Now that the Covid-19 pandemic is easing, trade between the United States and China will resume a more normal pattern of growth, but the difficulties of recent years, especially in terms of disrupted supply networks gives a hint of the enormous economic disruption that would accompany a war over Taiwan. Even clearer evidence of economic disruptions caused by war is offered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and its aftermath. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the Ukraine conflict might cost the global economy $2.8 trillion over 2022-23 (Hannon 2022). There has been particular focus by global strategists on the implications for microchip production in the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, since the island is a major global chip fabrication center (Zinkula 2022). But that is far from the only major supply disruption to the US economy that could result from a war, considering that the United States is dependent on Chinese production of goods ranging from acetaminophen (the most common pain killer) to car parts (Pletka and Scissors, 2022). Indeed, a recent study concludes: “…the scale of economic activity at risk of disruption from a conflict in the Taiwan Strait is immense” (Vest, Kratz, and Goujon 2022).

The asymmetric interest problem

A future American president confronting the dilemma of whether to intervene directly in a Taiwan scenario would, in addition to the nuclear and economic risks outlined above, also face a stark problem at the very root of the Taiwan dilemma: There is simply no getting around the fact that this issue is of much greater salience to China than it is to the United States.

Indeed, Beijing has made the Taiwan issue central to its ideology since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. China has stated that Taiwan represents a “core interest” that it will go to war over—no matter the consequences. In three previous major crises, China has indeed come up to the brink of conflict. And it has also “pushed the envelope” and “bared it teeth” menacingly, most recently in August 2022 when US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi made a visit to the island. For China, reunification with Taiwan is seen as dispelling the last vestige of China’s “century of humiliation” in order to claim what it calls “national rejuvenation.” Instead of gradually receding with globalization, China’s nationalism and approach to Taiwan only appears to be growing more nationalistic and aggressive.

In contrast, the United States has no comparable stake in Taiwan. Unlike Japan or the Philippines, Taiwan is not a treaty ally of the United States, since the bilateral defense treaty was abrogated in 1979 as a condition for establishing diplomatic relations with Beijing. While there are robust trade linkages, including both high technology microchips and arms sales, a majority of Americans cannot even locate Taiwan on a map (Kendrick 2022). While it is often claimed that the credibility of US alliances would be at stake in a Taiwan conflict, this seems far-fetched as there is no major military or strategic reason why US national security would be imperiled by a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. This asymmetry of interests may cause significant instability with respect to the dynamics of the crisis over Taiwan, since Beijing is quite clearly willing to run very significant risks to the delicate US-China relationship. By contrast, Washington has traditionally relied on ambiguity

But this time-honored approach may no longer support crisis stability, unfortunately.

The historical problem

The stark imbalance of interests is not simply the result of geography, although that explains much of the issue, but also the result of Taiwan’s very complex history that few Americans are aware of. It is not unreasonable to suggest that Taiwan could have turned out quite similarly to its Polynesian cousins and even been part of Indonesia or the Philippines. After all, the island— like both these Pacific archipelagic states—was colonized by both the Spanish and the Dutch. Yet, the Chinese empire consolidated control over Taiwan in the mid-17th century and ruled it for 200 years until Japan conquered it in 1895.

Japan’s conquest forms the nub of the historical problem, because this fact tends to aggravate intense Chinese nationalism. After all, many Chinese view unification as the path to remove the last stain of the “century of humiliation,” and particularly to redress finally Japan’s cruel predations against China from 1931-45. Perhaps 20 million Chinese died in the war resulting from Japan’s invasion of China (Bender 2014). That Japan has never made reparations for this invasion exaggerates China’s bitterness, and much of this resentment becomes activated in debates concerning Taiwan’s future, stimulating the ever-present sense of crisis in Cross-Strait relations.

As to Washington’s policy concerning the island’s fate, the foundation was seemingly laid down by President Franklin Roosevelt at the Cairo Conference in 1943 when it was agreed that all such territories, including Taiwan explicitly, were to be returned to China. President Harry Truman affirmed that policy in January of 1950, but he did introduce some ambiguity into the question when he ordered the US Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait after Kim il-Sung’s forces invaded South Korea. A number of severe crises, with nuclear reverberations, followed in the 1950s and the United States even deployed tactical nuclear weapons into Taiwan for about a decade in the 1960s. Thankfully, these weapons were removed along with all other US forces as part of the rapprochement orchestrated by President Richard Nixon in 1972. As part of that vital process, which allowed the normalization of US-China relations, Washington “acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position” (US State Department, 1972). Regrettably, that “One China Policy,” which resulted from those difficult negotiations back in the 1970s, is crumbling today and is a major cause of regional and global instability.

The alliance problem

American strategists put a lot of faith in their alliances, generally. The globe-spanning partnerships on issues ranging from institutional reform to weapons development are said to promote the existing “rule-based order.” In the Asia-Pacific region, the United States has a clutch of powerful and loyal allies, including Australia, Japan, and South Korea. India is more distant, but has a difficult relationship with China, and it could cause problems for Beijing if New Delhi wished to do so. Washington has been shepherding along the concept of the “Quad,” which involves the United States, Japan, Australia, and India, as a foundation for a possible NATO-like alliance in the Asia-Pacific. The innovative AUKUS agreement, linking London, Canberra, and Washington in a weapons technology agreement that highlights nuclear submarines, is another attempt to deter China mainly on the delicate Taiwan issue.

However, alliances do not provide an easy solution to the Taiwan dilemma. India is far from Taiwan and would not likely get involved in a war over Taiwan. Somewhat similarly, Seoul is also wary and focused on another potent threat—namely North Korea. Some in Tokyo regard Taiwan’s autonomy as vital to Japan’s national security, but Japan’s “peace constitution” and related legal complications could hinder Japan’s actions during a US-China war for Taiwan. Given Japan’s colonial history with Taiwan, it is even possible to consider that Tokyo’s involvement may aggravate the situation more than stabilize it. Finally, AUKUS is also no “silver bullet” for the on-going Taiwan Strait crisis. After all, Australia’s hypothetical nuclear submarine force would not be built and deployed for at least a decade (Westcott 2022).

The military problem

Of all the problems discussed above, none are quite as vexing and as crucial as the military balance in the western Pacific. For decades, military analysts considered China’s military to be a corrupt and backwards organization, possessing obsolete weapons and quite lacking in combat experience to boot. During the 1995-96 crisis, US Navy carrier groups in the vicinity of Taiwan maintained a deterrent posture and all but challenged Chinese forces to dare make a move against the island. Today, US aircraft carriers, submarines, and jet fighters maintain a certain qualitative level of superiority over their Chinese counterparts but it is not on the scale of the 1990s.

Beijing began to reform its armed forces in earnest in the wake of the humiliating 1995-96 crisis. It took decades for Chinese military modernization to hit its stride, but today the People’s Liberation Army looks like the armed forces of a growing superpower. The Chinese ground forces now wield not only advanced armor and artillery, but also hundreds of modern attack and transport helicopters. Pilot training (often measured in flight hours in the cockpit) in the Chinese Air Force is starting to approximate that undertaken in the United States. The PLA Air Force possesses fifth-generation fighters, large transports, battle management aircraft, along with an airborne (parachute) corps. China also has the “largest force of long-range surface-to-air (SAMs) missiles in the world” (US Department of Defense 2022).

Meanwhile, the PLA Navy now operates quiet air-independent propulsion diesel submarines, a new generation of nuclear submarines, and aircraft carriers too. The new Type 055 cruiser amounts to a very formidable, modern surface combatant (Caldwell, Freda, and Goldstein 2020). As another example of China’s naval prowess, the PLA Navy’s front-line anti-ship cruise missiles ASCMS (YJ-18 and YJ-12) are superior to American equivalents in terms of range and speed. There are also PLA “ship-killer” missiles currently operational, for which there are simply no American equivalents at all, including the anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBM) DF-21D and DF-26, or the DF-17, China’s new hypersonic weapon.

Nobody can say for sure what would happen in the event of a US-China showdown over Taiwan. But it is widely recognized that the balance has been gradually shifting, so that a situation once well within the Pentagon’s grasp has now become a tossup—at best. US ground forces are far away and have no realistic way to enter the theater of operations. American air power is similarly constrained, since Washington and its allies have far too few air bases in the region compared to China. Moreover, those that do exist, such as in Okinawa, are highly vulnerable (Pettyjohn, Metrick and Wasser 2022).

US aircraft carrier groups will not likely approach within range of Taiwan due to the risks of operating within range of China’s very formidable missile forces—not to mention the threat posed by submarines and other platforms that comprise the PLA’s so-called “access denial” arc across the western Pacific. Only US and allied submarines have a substantial chance of engaging in successful combat in the vicinity of Taiwan. But it is far from certain whether that force could prevail or not under the most arduous battle conditions—not least of which would concern the problematic resupply of torpedoes. In short, there is no obvious military solution to the Taiwan issue—even when putting aside nuclear weapons.

Conclusion

In aggregate, the problems above combine to make Taiwan the most challenging and most perilous problem confronting the United States and the world in the 21st century. As demonstrated, the military balance is shifting in China’s direction and this trend will likely continue, particularly as Washington’s attention is unquestionably focused on the ground combat in Ukraine. The economic risks of a major showdown with China over Taiwan are horrendous.

Yet, China has doubled down on its campaign to pressure the island and is likely willing to take more and more risks as demonstrated in the August 2022 crisis, since Taiwan forms the most burning and urgent unresolved issue in the nationalist ideology of Chinese Communist Party ideology. The historical record suggests, moreover, that previous US leaders have dealt cautiously with the Taiwan question—understanding that this could set the two countries on a course for war. Nor are alliances likely to head off this prospective catastrophe. Rather, the congealing of a full-blown anti-China alliance on the pattern of NATO could actually incite the war it is aiming to prevent.

While the tragedy of the Ukraine war might well have injected some caution into Chinese thinking, it has also likely made the Taiwan question more acute in some respects. Beijing has had concerns about the NATO alliance going back well before the Ukraine war, but Chinese leaders are clearly quite sympathetic to Russia’s objections to the Western alliance developing further strong points in its immediate backyard.

For Beijing, an analogous logic and very similar sensitivity applies to Taiwan’s status. Yet, the analogy could also be misleading in some ways, including for Western strategists. After all, unlike Ukraine, Taiwan likely could not be reinforced during a war since it will almost surely be blockaded and thus completely isolated. The island is also about 15 times smaller than Ukraine, while China’s military budget is considerably larger than that of Russia. In short, the Ukraine war has likely not saved Taiwan.

Yet, the impetus to save the island from Chinese designs is a strong impulse in the West and particularly among American foreign policy elites. That impulse is unfortunately driving the United States and China headlong into a tragic and preventable war. A more realistic approach, and one premised on the wise policy of military restraint, would understand that the United States cannot control all outcomes in the world, not least along the borders of other great powers. Hong Kong could not be “saved” from Beijing’s rule and, ultimately, neither can Taiwan, regrettably. The risks, including the possibility of regional or global nuclear war, are simply far too great. Even if the worst can be avoided, the immense costs of militarized rivalry would still dictate that Washington should draw its “red line” in the Pacific in a more cautious, pragmatic way. Indeed, it would be wholly reckless and irresponsible to draw this line over Taiwan.

Wise diplomacy is needed now to halt the inexorable slide toward US-China war over Taiwan. This would entail both Washington’s re-embrace of its former One China Policy, an effort to build confidence and trust in US-China relations and across the Asia-Pacific region, along with invigorating negotiating efforts to orchestrate peace and reconciliation in the Taiwan Strait.

Lyle Goldstein

Lyle J. Goldstein is the director of Asia Engagement at the Washington DC think tank, Defense Priorities. He is also a visiting professor at the Watson Institute for Public and International Affairs at Brown University. Goldstein previously served 20 years as research professor at the US Naval War College, where he received the Superior Civilian Service Medal for his pioneering research on Chinese military development.