Israel wants to create deserts all around and call it peace. Since October 7, something has become evident to its leadership, beyond the shortcomings of Israeli security, namely that the Zionist enterprise is at an impasse. Israeli politicians for decades have tried to erase the Palestinian presence in their midst, and yet the Palestinians remain. Some 5 million live between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River, in addition to the 2 million Arabs in Israel. The Israelis have quietly realized that without a major ethnic cleansing project, the higher Palestinian birth rate will slowly turn against them, as Israel’s Jewish population is around 7 million.

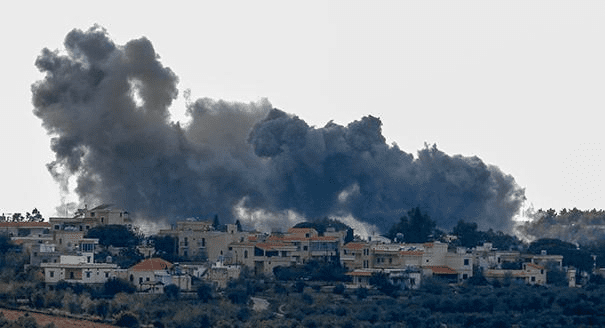

However, such fears have not come in isolation. For the Israelis, the emerging Palestinian demographic majority in Israel and the occupied territories is all the more dangerous because it is supported by well-armed militia groups bordering Israel, above all Hezbollah, themselves backed by Iran, a regional power. That is why some Israeli politicians today would like to extend the Gaza war to Lebanon, on the assumption that as the United States is covering for Israel in Gaza, it may provide an opening for a major military operation in the north.

There is certainly a fear among some U.S. officials that Israel intends to use the weaponry it has received from Washington in a war against Hezbollah. However, the idea that the Americans would green-light such a war seems, for now, unlikely, not least because the chances are high that it would expand into a broader regional conflagration that draws in the United States and Iran. From the start of the Gaza war, the Biden administration and Iran have engaged in back-channel talks, which has kept the situation in Lebanon in unstable stability, with Hezbollah and Israel attacking each other, albeit within what are seen as the red lines of engagement.

However, are the Israelis really reassuring on that front? It’s entirely possible that they will seek to initiate a conflict in Lebanon and push the Biden administration into making a hard choice of either helping them, or paying the political price for failing to do so. That would be extremely risky, of course, not least because Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is seen by some in Washington as someone who has an interest in widening the conflict in the region to save his political skin.

As one State Department official explained to the Huffington Post, “This is a pivotal moment in history, and we should feel angry about how Netanyahu has literally put our reputation on fire to advance his personal political agenda. The collateral effects to American security are extremely consequential.”

Neither the Americans nor the French are taking risks with Israel. A few weeks ago, the Biden administration sent Amos Hochstein to Beirut to send a message to Hezbollah that the United States was not looking for a war in Lebanon. Hochstein, who helped negotiate the maritime boundary between Lebanon and Israel, also reportedly sought to see about negotiating the two countries’ land borders, though press reports at the time suggested that Hezbollah was not yet ready for this.

However, the situation today is extremely risky for several reasons. First, even if the Gaza conflict ends with a ceasefire, no similar formal arrangement may be in place to calm the front in Lebanon. In other words, Israel could retain the latitude to continue to hit targets in the country, and then demand concessions in exchange for ending its military campaign. Among these concessions, the most likely would be to secure a withdrawal of Hezbollah units to behind the Litani River, allowing Israelis living near the northern border to return to their homes.

The Israeli demand is in line with Security Council Resolution 1701, which brought the 2006 Lebanon war to an end. The resolution called for “security arrangements to prevent the resumption of hostilities, including the establishment between the Blue Line and the Litani river of an area free of any armed personnel, assets and weapons other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL [the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon].” Moreover, Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati stated recently that Lebanon was committed to Resolution 1701. In other words, it would be tricky for Hezbollah to reject an initiative to redeploy away from the border if it means openly violating a UN resolution backed by Beirut.

In the past month and a half, France has also sent officials to Lebanon to avoid a deterioration of the situation there. First, Paris dispatched the foreign minister, Catherine Colonna, then the defense minister, Sébastien Lecornu, followed by presidential envoy Jean-Yves Le Drian, whose focus was on extending the term of the Lebanese armed forces commander, Joseph Aoun, beyond January. Finally, in the past week, the head of France’s foreign intelligence service, Bernard Emié, reportedly acting in coordination with Arab and non-Arab states who follow events in Lebanon closely, was in Beirut to propose a solution that would end the fighting in the south and push Hezbollah forces to behind the Litani. According to media reports, the party rejected this, saying it would only stop striking Israel once the Gaza conflict came to a conclusion, and that when this happened the situation in Lebanon should return to what it was before October 7.

However, there is an opening for a compromise that belies the party’s pushback. Emié, a former ambassador to Lebanon, who has good contacts in the country, allegedly proposed that Hezbollah withdraw its elite Radwan unit to the Litani. What does that mean? Unless a force is put in place that controls each male who enters southern Lebanon, a near impossibility, we can assume Radwan members would reenter the region at will, as many originate from and have family there. The same thing happened with Resolution 1701 in 2006. In no time, Hezbollah was again present south of the Litani, because neither the Lebanese army nor UNIFIL had the authority to bar the return of party members to their villages.

Hezbollah is aware of this reality, and therefore its negative reply to Emié has to be interpreted with caution. Certainly, it is unwilling to commit to a cessation of hostilities before the end of the Gaza war, but once a ceasefire is reached, Hezbollah would probably be keen to agree to a formal end to the fighting in Lebanon, if only to avoid any ambiguity that Israel might exploit to launch a war.

The main question will be whether the Israelis are willing to accept this deception. The Netanyahu government may not look like it is in the mood for this, but several things play in favor of its agreeing. First, a war with Hezbollah could represent a major regional escalation, one that may lead to significant destruction in Israel. Given Netanyahu’s domestic opposition, support for his government could shrivel if Israelis view a Lebanon war as an effort by the prime minister to ensure his political survival. Israeli zeal to punish Hamas does not necessarily extend to Hezbollah.

Second, the Americans do not want a Lebanon war, especially in an election year for Biden. The president has already faced blowback for having enabled Israel’s merciless operation in Gaza, so it seems highly improbable that he would give Israel the green light to extend the war in such a way that it might involve U.S. forces. Americans are fed up with endless overseas conflicts, and a new Middle East war would surely sink Biden’s reelection bid. Moreover, the administration has great leverage over Israeli decisionmaking that it can use. It supplies the weapons Israel would need to conduct the war, and might even decide that U.S. ships would not intervene if Israel provoked a conflict in Lebanon without American approval.

Third, a Lebanon war, particularly one in which Israel is perceived as the aggressor, would elicit much more of an angry reaction worldwide than the Gaza war, in which the opening shots were fired by Hamas. This, in turn, could threaten Israeli gains in Gaza, complicate Israeli objectives, and bring on an entirely new situation that Israeli firepower alone won’t resolve. To expand the war to Lebanon, Israel would probably need to prepare for a conflict with Iran as well, taking matters to levels with which the Israelis and Americans may be ill prepared to contend.

If Hezbollah agrees to pull its Radwan unit back from the border, on top of acceding to the international push to extend Aoun’s term as armed forces commander, it will demand something in exchange. The Lebanese consensus is that it will ask that Lebanon’s Arab and international interlocutors endorse Suleiman Franjieh as Lebanon’s president. If a package deal comes out of this, Franjieh’s Christian opponents may have no choice but to go along with it.

On the surface, such an arrangement could give something to all sides, even if it leaves questions unanswered. For example, would Hezbollah allow Hamas to suffer a major setback in Gaza without reacting? The fact that the party has refused to discuss any concessions before the fighting there has stopped would suggest not. But let’s assume its reaction remains limited, Hezbollah would then get the president it wants, Israel would be able to claim some sort of victory in Gaza, without a major Lebanese backlash, and return its citizens to their homes in the north, the Americans and Iranians would avoid a regional war, and Lebanon would be spared devastation, reassuring the country’s Arab and Western sponsors.

Too neat? Perhaps, but the Israelis must know that, ultimately, security on their borders is dependent on the competence of their military, not their enemies’ goodwill. Expecting the Radwan unit to remain permanently deployed away from Israel’s border, while asking the Lebanese army and UNIFIL to implement this, is naïve given Lebanon’s reality. Israel has little latitude to broaden the Gaza conflict, so under these circumstances, and given global condemnation of the carnage it has already visited upon the Palestinians, it may have to take what it can get.