Iranian President Hassan Rouhani suffered in the run-up to crucial elections in early 2016 what amounted to at least a symbolic defeat when state-run television banned Iran’s most popular soccer program from running an interview with his foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, on soccer and politics.

Amid confusion about the reason for the ban, Iranians worried that not only was their beloved, already highly politicized sport being dragged further into the country’s power struggle but also that government-controlled television was taking sides in a partisan struggle.

Iranian media reported that Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), the country’s broadcast authority, had banned Mr. Zarif’s appearance because of his liberal views and the fact that his appearance on the soccer show might brand him as a leader in the mould of nationalist president Mohammed Mossadegh, who was toppled in 1953 in a US and British-backed coup.

“Iran’s soccer diplomacy: ‘anything goes’ in fight for parliament seats,” said one headline referring to polling in February to elect both the Islamic republic’s legislature as well as its Assembly of Experts, the forum that appoints the country’s spiritual leader. The assembly, which is elected for a period of eight years, could well be the first in 26 years to appoint a new spiritual and political leader with 76-year old Ayatollah Ali Hosseini Khamenei believed to be suffering from prostate cancer.

Former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a moderate who headed the assembly until 2009 said in a reference to Mr. Khamenei’s health that the council had recently “appointed a group to list the qualified people that will be put to a vote (in the assembly) when an incident happens.”

He said Iran was “getting ready for determining its fate for years to come” with February’s elections for parliament and the assembly. Mr. Khamenei has rejected attempts in recent months by Rouhani to limit the assembly’s ability to bar moderates from standing as candidates.

Efforts by hardliners with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) in the lead to control soccer underline the importance of the pitch as a battleground in the struggle for Iran’s future in the wake of the nuclear agreement with Iran and the expected lifting of stringent United Nations sanctions that Western nations hope will boost Mr. Rouhani in the elections.

The significance of soccer has been heightened by Iran’s poor international performance as well as allegations of match-fixing scandals that have forced the guard to justify its involvement in the sport.

In a recent interview with sports magazine Tamashagaran Emrooz (Today’s Spectators), Guards commander Azizallah Mohammedi, a former board member of the Football Federation of the Islamic Republic of Iran (FFIRI) argued that the military group’s involvement in soccer had grown from the fact that some of its members had played soccer in the past. He said they had become soccer managers not as part of a Guards strategy but because of the qualifications and skills they brought to the table.

Mohammed Dadkan, who served as FFIRI president from 2002 to 2006, however dismissed Mr. Mohammedi’s portrayal in an interview in August. “Managers in the world of football world are corrupt. Unfortunately, people who know nothing about football are involved in this sport – managers from the Guards and the Law Enforcement Forces,” Mr. Dadkan said.

IGRC commanders have served at various times as head of Persepolis FC, one of Iran and Asia’s top clubs while Lotfollah Forouzandeh Dehkordi, a guard commander and former vice-president under Rouhani’s hard-line predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, is a member of its board.

Fajr Sepasi FC, a club in Shiraz owned by The Organization for Mobilization of the Oppressed or Basij, a voluntary militia associated with the guards, is directed by Colonel Zohrab Qanbari Mahardou.

Brigadier-General Gholam-Asgar Karimian is chairman of Tractor Sazi FC, a top flight club in Tabriz, the capital of East Azerbaijan, whose supporters have protested in recent years against the government’s environmental policy and at times raised Azeri nationalist slogans. The club’s president is former Guard Saeed Abbassi while another commander, Mostafa Ajorlou, the guards’ former head of physical training, is a member of its board.

Traktor Sazi is owned for 70 percent by the city’s state-owned tractor company, which in turn is owned by Mehr-e Eqtesad-e Iranian Investment Company that was sanctioned by the US Treasury as a subsidiary of Mehr Bank, an IGRC financial institution. The remain 30 percent by the Defence Ministry’s by Kosar Financial Institution.

Mr. Ajorlou, wh en he headed Steel Azin FC before joining the Traktor Sazi board, tried to sack top Iranian player Ali Karimi for allegedly not fasting during Ramadan and questioning the commander’s decisions.

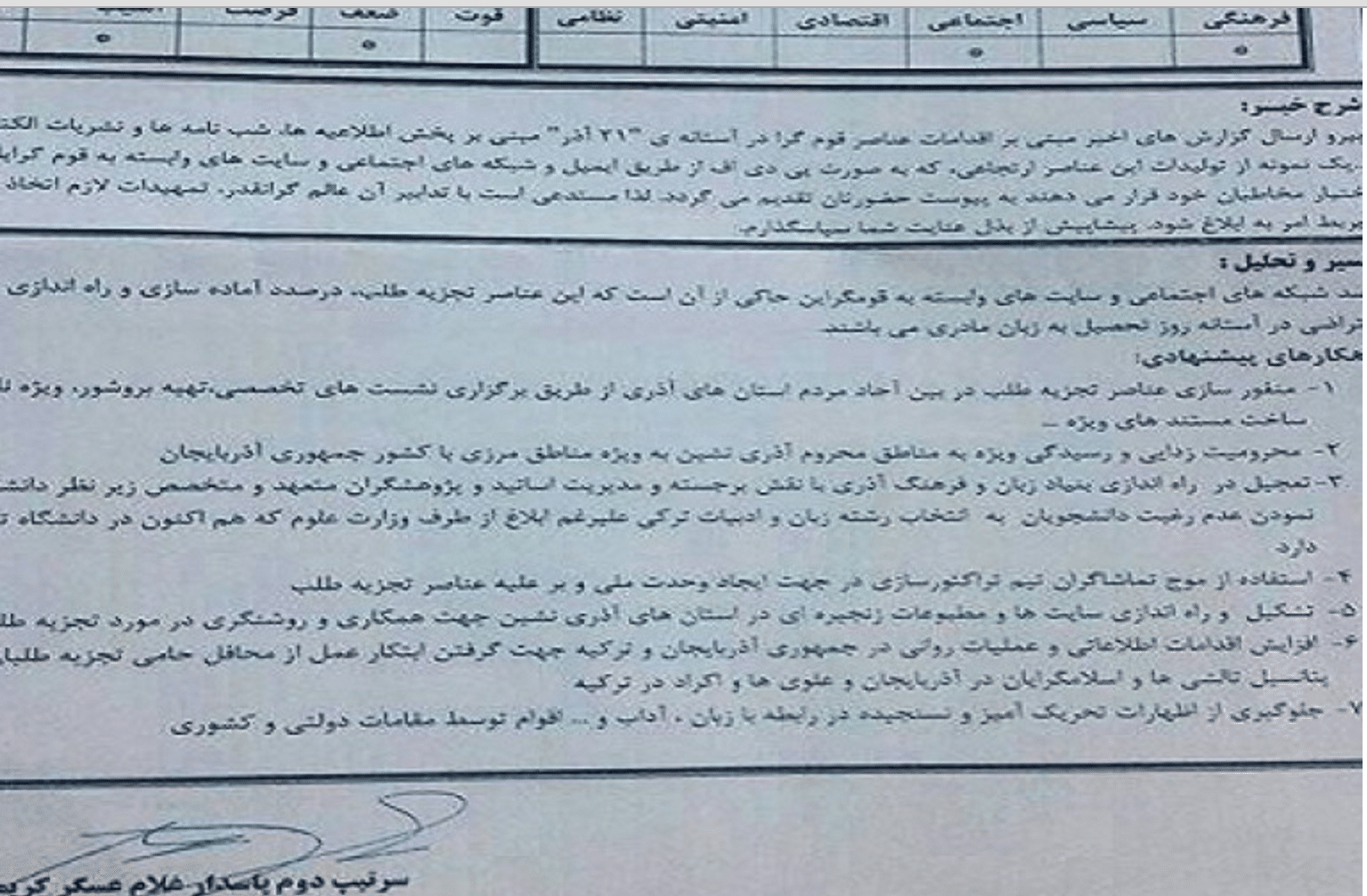

Azar news, a news agency operated by the National Resistance Organization of Azerbaijan (NROA), a coalition of opposition forces dominated by the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, a group that was tainted when it moved its operations in 1986 to Iraq at a time that Iraq was at war with Iran, this month leaked a letter allegedly written by General Karimian detailing how Traktor Sazi could be used to unite Azeris against what the general termed “racist and separatist groups.”

The letter said the groups were campaigning for a “study the mother tongue day.” It suggested that the mother tongue referred to was Talysh, a dying northwest Iranian language that is still spoken by at most a million people in the Iranian provinces of Gilan and Ardabil and the southern Azerbaijan.

The letter implied that the groups General Karimian was concerned about were Azeris separatists, Islamists and Turkish Alevis, a sect viewed as heretical by orthodox Islam that accounts for up to 20 percent of Turkey’s populations.

If anything, the letter’s focus appeared to advocate measures to weaken Azeri separatist groups by combatting widespread racist attitudes towards Azeris and improving services in East Azerbaijan. Racial attitudes towards Azeris is something Traktor Sazi knows a lot about.

“Wherever Tractor goes, fans of the opposing club chant insulting slogans. They imitate the sound of donkeys, because Azerbaijanis are historically derided as stupid and stubborn. I remember incidents going back to the time that I was a teenager,” said a long-standing observer of Iranian soccer.

As a result, stadia in which Traktor Sazi Tabriz FC play are repeatedly the venue for protests demanding greater rights for Iran’s Azeri minority. During one clash in 2013 in Teheran’s Azadi stadium with the capital’s storied Persepolis FC, Traktor Sazi supporters unfurled a banner saying in English: “South Azerbaijan isn’t Iran,” a reference to East Azerbaijan that borders on Azerbaijan.

James M. Dorsey is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, co-director of the University of Wuerzburg’s Institute for Fan Culture, a syndicated columnist, and the author of The Turbulent World of Middle East .