Istanbul–

Salman Rushdie, the writer of Satanic Verses, a novel that ignited outrage among some religious circles, who considered its content to be blasphemous and was banned in some countries, is known by many as “a sheer enemy of Islam and its communities”. The stabbing attack on him was celebrated among some Islamic circles and Hezbollah supporters. But many do not know Rushdie was promoting the Palestinian Cause!

In a video clip from 1986, Rushdie reads Mahmud Darwish poem to the audience at the London Institute of Modern Arts and introduces his guest Edward Said with detailed compliments. Rushdie laterly published the text of the conversation on his book named “After The Last Sky”, a collection of interviews and articles on palestinian cause.

Here’s the transcription of the first 5 minutes of the one-hour-long conversation:

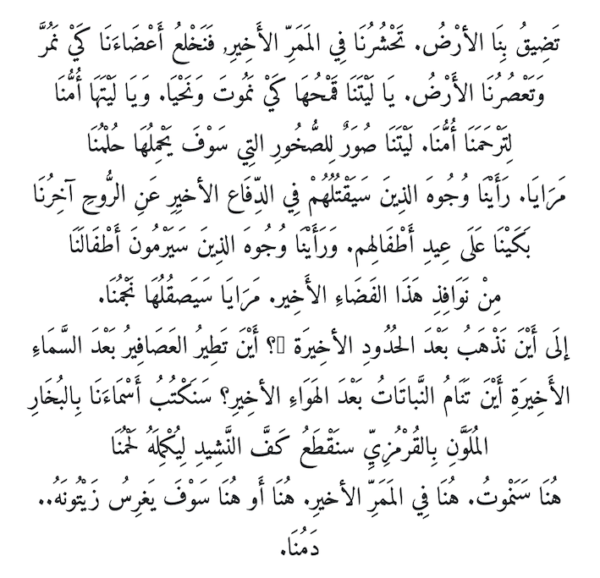

“After the Last Sky is a collaborative venture with Jean Mohr—a photographer who may be known to you from John Berger’s study of immigrant labour in Europe, A Seventh Man. Its title is taken from a poem, The Earth is Closing on Us’, by the national poet of Palestine, Mahmoud Darwish:

The earth is closing on us, pushing us through the last passage, and we tear off our limbs to pass through.

The earth is squeezing us. I wish we were its wheat so we could die and live again.

I wish the earth was our mother So she’d be kind to us.

I wish we were pictures on the rocks for our dreams to carry as mirrors.

We saw the faces of those to be killed by the last of us in the last defence of the soul.

We cried over their children’s feast. We saw the faces of those who will throw our children

Out of the window of this last space. Our star will hang up mirrors.

Where should we go after the last frontiers? Where should the birds fly after the last sky?

Where should the plants sleep after the last breath of air?

We will write our names with scarlet steam,

We will cut off the hand of the song to be finished by our flesh.

We will die here, here in the last passage. Here and here our blood will plant its olive tree*

After the last sky there is no sky. After the last border there is no land. The first part of Said’s book is called ‘States’. It is a passionate and moving meditation on displacement, on landlessness, on exile and identity. He asks, for example, in what sense Palestinians can be said to exist. He says: ‘Do we exist? What proof do we have? The further we get from the Palestine of our past, the more precarious our status, the more disrupted our being, the more intermittent our presence. When did we become a people? When did we stop being one? Or are we in the process of becoming one? What do those big questions have to do with our intimate relationships with each other and with others? We frequently end our letters with the motto “Palestinian love” or “Palestinian kisses”. Are there really such things as Palestinian intimacy and embraces, or are they simply intimacy and embraces — experiences common to everyone, neither politically significant nor particular to a nation or a people?’

Said comes, as he puts it, from a ‘minority inside a minority’—a position with which I feel some sympathy, having also come from a minority group within a minority group. It is a kind of Chinese box that he describes: ‘My family and I were members of a tiny Protestant group within a much larger Greek Orthodox Christian minority, within the larger Sunni Muslim majority.’ He then goes on to discuss the condition of Palestinians through themediation of a number of recent literary works. One of these, incorrectly called an Arab Tristram Shandy in the blurb, is a wonderful comic novel about the secret life of somebody called Said, The Ill-Fated Pessoptimist. A pessoptimist, as you can see, is a person with a problem about how he sees the world. Said claims all manner of things, including, in chapter one, to have met creatures from outer space: ‘In the so-called age of ignorance before Islam, our ancestors used to form their gods from dates and eat them when in need. Who is more ignorant then, dear sir, I or those who ate their gods? You might say it is better for people to eat their gods than for the gods to eat them. I would respond, yes, but their gods were made of dates

doesnt mean he advocates today’s extremist movements