It’s hard to imagine, but this attractive young woman was one of the boldest Mossad agents to ever serve the agency, taking part in several major operations, and earning the Chief of Staff’s commendation.

by Amira Lam

She was young, beautiful, and one of the Mossad’s most daring operatives. No one knows what she looks like today as current photographs of her are classified, but in a new book, Yael sheds light on the shadowy, legendary work of the Mossad.

On April 9, 1973, at 7pm, Yael met an Israeli man named Eviatar for dinner. They sat in a genteel restaurant in Beirut’s Phoenicia Hotel. She wore a chic, elegant sports jacket, with a green scarf draped on her neck. They drank wine, enjoyed the food, and talked. An eavesdropper would have had no idea that these were two operatives in the Mossad’s Caesarea unit, the secret agency’s operative arm – or that Yael was meeting her boyfriend for a secret mission.

He asked her about her neighborhood, about the view in her apartment. “And what about the neighbors who live across from you?” He wondered. The names remained unuttered, but they knew what he meant.

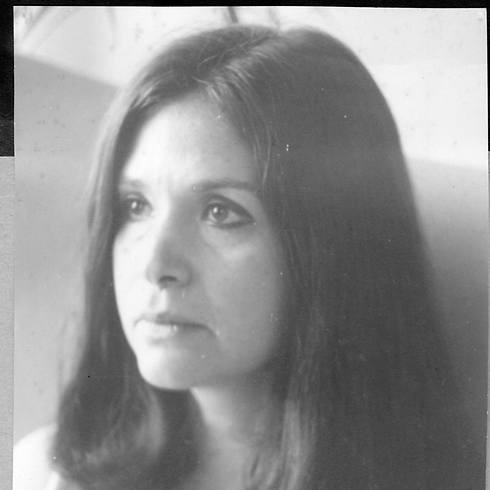

Yael during her operational years

Two months earlier, Yael had rented an apartment across the street from the apartments of several interesting figures: Kamal Adwan, a high-ranking member of the Black September terror organization; Mohammed Yousef al-Najjar, the head of the PLO’s branch in Lebanon; and Kamal Nasser, the PLO’s spokesman. Yael monitored the men from her windows. “They’re home today, all three,” Yael told Eviatar. Silence fell, but only momentarily.

“He told me to go straight to my apartment and stay in the back, far from the windows,” Yael remembers years later. “‘We’ll meet in the next few days,’ he told me.’I’ll let you know where and when’. I naively thought he worried too much about me.”

Yael didn’t know that just then, while she was eating her dinner, IDF troops were already out in the sea, waiting for approval to come ashore in Beirut. And she didn’t know that her statement about the three men being home would be the opening shot of Operation “Spring of Youth,” considered one of the most audacious operations in the history of Israel’s security services, in which elite IDF units and the Mossad killed the three senior Palestinian terrorists, who were among those responsible for the murder of 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics.

I met Yael this week at her apartment in central Israel. At 79, and despite poor health, she is still an impressive woman. A new book, “Yael –the Mossad’s Warrior in Beirut”, was written by Efrat Mas after speaking to Yael and her colleagues over the course of two years. Of course, Yael is her undercover name given by the Mossad; her identity is still under wraps.

What happened to you that night, after you separated from your partner in the operation, Eviatar?

“I wandered around Beirut’s downtown for a bit. I was in a good mood. I was so happy to meet someone from the office and feel at home for a moment. He said he would meet me again in a couple of days and that misled me, so I was completely calm. I arrived at the apartment at around 9pm. I checked, like I always did, if anyone had entered while I was gone, and then I went to the window to see if ‘the three objectives’ were still in their apartments.

“Mohammed Najarr and Kamal Adwan lived in two apartments on the sixth floor right across from me. Kamal Nasser lived n the building adjacent to theirs, on the third floor. The lights were on in the three apartments. I heard the sound of cars coming and going. I was satisfied that the information I had passed on at 7pm was still up-to-date, and went to sleep.”

A few hours later, she heard gunshots.

“I crawled on the floor and peeped outside to see what was happening,” she recalls. “Three large vehicles were parked on the street. The shots got louder, there were screams, and the lights in the three apartments turned on. Everything happened quickly and suddenly I heard ‘come here, come here’, in Hebrew.

When I heard Hebrew in the heart of Beirut, I knew that was it, there was an operation underway, and I connected what was happening with the information I had given to Eviatar a few hours earlier. After all, I wasn’t quite that naïve. I remember saying to myself, “I am just doing my job’. I did what they told me to do, that’s all.”

And were you scared?

“I was afraid they might shoot me by mistake, as only a narrow road separated my window from their apartments. The Israeli fighters didn’t know I was there, they know there was real-time intelligence but they didn’t know exactly who, where, and how. Many years after that, when we lived in Caesarea, Major General )Ret.) Amiram Levin was our neighbor. One day we got to talking. He took part in the operation; he was a Major, and acted as deputy to the mission commander Ehud Barak. He told me that they knew their had to be a Mossad agent present in order to convey the real time intelligence, and that he always asked himself where this person was, The seeing but unseen, and how he could prevent accidentally hitting them. I was that person. I stood by the window and everything happened very quickly, and then there was a sudden silence for a few minutes, until the police and army forces began arriving on the scene.”

So then what did you do?

“I sat by my writing desk, which was situated right under my window, and I wrote to my contact at headquarters about the night’s events, under the pretext of a love letter. Among other things I wrote: ‘Emil my dear, I am still shaking from last night’s events, I woke up suddenly in the middle of the night from the sound of explosions. I ran to the window and saw a battle taking place in the street. It was awful, I ran back to the other window, where I thought I would be protected from an errant bullet, after a few hours the quiet returned, and to my surprise I fell asleep. When I woke up I thought it was all just a bad dream. But no, it was reality; those awful Israelis were really here. I think I might take a vacation and visit you during the Easter holiday. Lovingly yours, Reeba, your nun in Lebanon.’ In the writing I hid the sentence: ‘It was a great show last night. Well done!”

Yael during her active years

In the book you say that it was precisely on the night of the operation that you in fact thought about your parents back in the US.

“Yes, it was when I returned from a meeting with Eviatar. It was free time for me. I was relaxed, I had a great evening, and I didn’t feel responsible for anything at that moment. I snuggled up on the couch in my room, and suddenly I began thinking about my parents, on my path from the US to Beirut. I thought to myself that if my parents would have known where I was now, they would have been shocked, and wouldn’t have understood what happened to their soft and innocent daughter.”

Drafting

The meeting with Mike Harari

Nothing in Yael’s previous life could have hinted at her participation in one of the boldest operations ever conducted by the Israeli security apparatus. She was born in Canada and grew up in New Jersey, in a warm and supporting household. Her father held a doctorate in physics, and her mother was a housewife. The family only had coincidental ties to Judaism.

“In our neighborhood there were only three Jewish families,” she says, “so we didn’t really know a lot about Judaism. We weren’t a Zionist or Jewish household. We had a Christmas tree at home. My dad didn’t pay much importance to religion. Science and scientific thinking were his whole world. I remember running into anti-Semitism just once as a child. It happened when a kid was walking behind me, and said ‘move dirty Jew.’ I turned around and told him, ‘I’m a Jew but I’m not dirty.’ But besides that moment, I didn’t have a Jewish or Zionist experience.

Despite that you made aliyah.

“The main reason was that I was in a bad marriage, and I wanted to get far away from my husband. We fought a lot, and I though I would go for a year. Later on more reasons piled up which pushed me towards Israel, mainly the fear that abounded before the breakout of the six day war that Israel’s existence was in jeopardy. I always identified with the underdog, and unlike the might of the US, Israel looked like someone who needed a hug.”

How was your first meeting with Israel?

“I had family here who I met while they where emissaries in the US, and they helped me with the first steps. I went to ulpan, but because I didn’t really plan on staying for that long I didn’t learn Hebrew. In fact, I was never really settled in Israel. I worked as a computer systems analyst, I was lonely, and then, in the beginning of 1971, three years after arriving in Israel, I had a relationship with an Israeli man, and he told me he worked as a body guard in the Mossad. It will surely sound weird, but I heard the word Mossad and something happened to me. Something almost mystical. I felt like it was my destiny, that this is what I was meant to do with my life. I asked my friend to put me in touch with the Mossad, and tell them that I wanted to join. He did so, and for a few weeks no one called.”

“A few months later I received a call. The man on the other side of the line did not identify himself. He only said to me: ‘Do you want to do something for the country?’ I answered yes. We scheduled a meeting at a café. There were two men there, and they asked me all kinds of questions, but what I remember most was that at the end of the meeting I asked if either one of them needed a ride home. One of them did, and we started walking towards my car, and I forgot where I parked. It took us a while until we found it. When I got home I thought ‘that’s it’ they will never recruit me to the Mossad, they will never take someone who can’t find their car. But after two days I got another call and I was invited to a meeting, that’s when I met Mike Harari”(commander of the Mossad’s “Caesarea” unit).

What happened in that meeting with Mike?

“We met on a Saturday afternoon in an empty office building in Tel Aviv. Mike had a deep voice, and spoke slowly, with a glance that changed from soft to stern. I was in suspense. I told him my life story; he asked a lot of questions about my decision to come specifically to Israel, and my feelings about being here. At a certain point I told him I decided to join the Mossad because ‘I want to be worth something, I want to do something worthwhile.’ In hindsight I know they were on the fence about me. Years later Mike told me that during that meeting he felt that I was very naïve, not knowing whether this would be to my benefit in lowering people’s guards’, or a weakness. He debated whether I was strong enough to confront the stress of covert work. He saw that I needed a supportive surrounding, and asked himself whether I could act alone in hostile environments, and whether my ‘femininity, softness and beauty,’ as he put it, where a strength or weakness. One month later I was invited to meet with the head of the Mossad, Zvi Zamir, and even he, I know in hindsight, had similar questions about the naivety I was broadcasting. At the end of the process they decided to accept me, and I started my training.”

And in hindsight, your Naivety and femininity helped you in your work?

“I think it helped. With the years I learned to use my naive look. I used it as a sort of manipulation. I was truly naive at first. You can see it in my response to operation Spring of Youth, where I didn’t really pick up on all the signs that the operation was set to begin. But slowly, with the years and the operations I took part in, I became less naïve, and I understood that things aren’t always what they seem, but I kept using my naïve persona, which often resulted in me looking helpless. It helped me in the target countries I visited during my service. Every where I went people asked how they could help me, like I was a little girl, especially the men in the Arab world. Something in my frail appearance didn’t raise suspicions. Arab men trusted me. I used it knowingly.”

Lebanon

“I looked for a cover story”

A short while after finishing her training in Israel, Yael received her first assignment. She was tasked with blending in with the locals in Brussels, the capitol of Belgium. She had an apartment, a job, and a well rounded social life. Three months after arriving in Brussels, she embarked on her first mission, in which she had to collect intelligence in Beirut. During the next two years she entered and departed Lebanon a number of times. At that point her handlers began preparing her for a longer stay in Lebanon.

Did they explain why?

“They told me it was part of a bigger effort against terror cells. It was after the Munich Olympics massacre, during a period fraught with terror. There still wasn’t a plan of aciton, but I also didn’t ask questions about something that didn’t have to do with my job. I focused on what I had to do, and I looked for a cover story which would allow me to stay in Beirut for a longer period of time, where I could be free to enter and leave.”

What was your cover story?

“We found that the role of an American novelist writing a screenplay for a movie set to be filmed in Lebanon answered all the criteria. I didn’t know how to ‘be a novelist.’ So I flew to Israel to undergo a shortened writing ‘course’, and ‘how to look like a novelist.’

“The course took place at the home of the novelist and biographer Shabtai Teveth, who was Mike Harari’s good friend. Teveth knew why I came to him, he seemed very professional and full of charm. He told me that ‘you cannot teach someone to be a novelist, but you can learn to look the part.’ He showed me his working rooms, his writing table full of papers, and how to organize a working table to look like a novelist. How to scatter drafts, pens, and books. He explained the different stages of writing, from the idea stage to the full text. I was there for a few days, and I really liked the intellectual atmosphere in his house. After Teveth’s instruction, I returned to Brussels, and looked for a topic for my screenplay. I wanted to focus on a woman who had ties to Lebanon and Beirut. I went to the library and looked for a woman that fit the profile. On one of the days I visited the Victoria and Albert museum in London. It was in the archives their that I learned of the Lady Hester Stanhope. I read about her and learned that she was perfect for me.”

Lady Hester Stanhope what can you tell me about her?

“She was born in 1776 to a noble family in England. She inherited a large sum of money and began travelling throughout Syria and Lebanon, something no other woman had done before, earning her the nickname ‘Queen of the East.’ She settled down in a crumbling monastery near Sidon, and turned it into a luxurious castle. Her persona charmed me, and without much if any skill I began writing the screenplay.”

Yael arrived in Beirut with the screenplay in hand. At first she lived in a hotel while looking for an apartment which would allow her to observe the three targets – Kamal Adwan, Mohamed Yousef al-Najjar, and Kamal Nasser. “I found an apartment which belonged to a man named Fuad Abud. He lived with his sisters in a building he owned, where he also rented out a few of the apartments. On the fourth floor there was an apartment which looked directly towards the two buildings in which the targets lived. I rented the apartment, and of course told the landlord about my screenplay.”

“The first thing I did was to put a large working table under the window, making sure to spread the books drafts and pens the way Teveth taught me to. It was a great observation post. I didn’t even need binoculars to see into the three target apartments. I was asked to report to headquarters when: the men were home, and when they were not, who was entering the apartment, their families, the guards, and generally the happenings near the building.”

Did you feel afraid, lonely?

“I lived alone in New York before, which isn’t easy, so living in Beirut wasn’t scary for me. Generally speaking, I felt protected as a member of ‘Caesarea.’ Even when I was alone they made me feel like I wasn’t lonely. I felt like we were all working towards the same purpose. Additionally, my neighbors in Lebanon, and my landlord were very warm and generous to me.”

The Operation

“It scares me that I wasn’t afraid”

The information that Yael and the others in Lebanon passed on was collected by “Caesarea’s” intelligence officer, and led the unit’s commanders to decide that a mission against the three targets was possible.

Zamir, Harari, and the “Ceasera” intelligence officer came to the Chief of Staff David (Dado) Elazar with the information they had collected. According to Harari’s recollection in the book, the decision was made to green light the operation in Dado’s office. They also decided that commandos from the: Sayeret Matkal, paratroopers Special Forces, and the Navy’s Shayetet 13 would be the ones to carry out the operation. “Caesarea” agents working with Mossad intelligence would be responsible for collecting the intelligence needed beforehand. The plan called for “Caesarea” agents to act as drivers, and lead the attacking forces through the streets of Beirut to and from their targets.

According to the book, Dado held a conversation in his office with high ranking Mossad officials saying: “I’m ready to go for it under the condition that there will be real time intelligence, in order to avert a situation where the complicated operation is initiated, and the soldiers arrive at an empty apartment.” Harari, in response, promised to organize the live intelligence source. That was Yael’s job. “Without Yael, who took upon herself the central position of real time intelligence collection, the operation would not have happened,” Harari wrote in his preface to the book.

A short while after the meeting with the Chief of Staff, Hariri met with Yael in Brussels and passed on her instructions. She remembers that meeting very well. “Mike told me to collect real time intelligence on the targets during the day and night. The word ‘operation’ was never used during the discussion. We talked about means of communication, and the reactions to the possible scenarios. He told me: ‘Yael, at the very end you will be there alone with the knowledge and the experience that you gained, and with who you are, put it all together and do it your way. I trust you.’ I told him: ‘Mike, I will report on what I see and find in real time.’ That was our language, we didn’t need many words.”

“At the time I didn’t think that Mike was giving me instructions before an operation,” Yael emphasized. “I returned to Beirut thinking I was observing these three individuals, who were the planners of several terrorist attacks, including the Munich massacre. I knew that there was an intention to launch an operation against them – not as revenge, but as a way of showing them that we can reach them anywhere in the world, but I never heard the words ‘mission’ or ‘operation’. I also didn’t ask about things that were not in my job’s purview or about other people in general. I focused on what I had to do.”

Three weeks after the conversation with Harari, Yael met with Eviatar in Beirut. “I knew Eviatar from a previous mission we conducted together a few months earlier, where I took photos of sensitive compounds in Beirut, but we acted like total strangers.” The two ran into each other completely by chance at the luxurious Intercontinental hotel Bar. “Didn’t I meet you in Paris at the Louvre?” She asked him. In a conversation between the two she updated him with current information on the targets.

Two days later, on the 9th of April, they met again, in a meeting that would mark the launch of “Spring of Youth.” Yael says she has never felt anger or frustration over her handlers not telling her the exact time of the operation. “That’s how we work and its one of the essential elements for anyone working in covert activities,” she clarifies. “I think that knowing only my task, made me feel less concerned, I was to act normally.”

“Later on, after I had returned to Israel, I met with Mike and told him that I never raised the thought that a mission would be launched without me knowing beforehand. Mike explained to me why it was important to compartmentalize me from the rest of the operators. He also said that the naivety with which I accepted the happenings around me protected me and assured that I would act naturally and trustingly. “

Yael remained in Beirut for five days after the operation. She was alone, in a hostile environment, while the local authorities were conducting a manhunt to find anyone responsible for helping the Israelis. Documents which later fell into her hands show that from the onset of the planning stages, she was to be obscured from IDF forces, so that she would not need to be evacuated, lest an emergency, and would leave Lebanon in a normal manner at the first possible window.

Did you know you were left alone, that the others had left?

“I didn’t know about the others, because I was instructed to cut ties with headquarters so as not to risk my safety. I had final instructions which I received from ‘Caesarea’ headquarters after the operation, and at first I tried to stick with them. I was told to leave my apartment immediately, and go to a hotel, telling the landlord that I am too afraid to stay in an apartment in a neighborhood where things like this happen, and that I should fly to Belgium after a week for a vacation. But when I approached my landlord, with whom I had a good relationship, and told him that I was afraid and wanted to leave, he looked frightened and told me that It was a terrible idea, that every sudden departure would raise suspicions. He told me I could live with him and his family until things calmed down. He brought one of his friends, whom I knew, in order to convince me. He too repeated that leaving suddenly would make me look suspicious, because they were looking for Americans.”

So what did you do?

“I was in a dilemma; whether to follow instructions or go with what I thought was right at the time, so I decided to act according to the advice of my Lebanese friends. Zvi Zamir later told me that I was the only agent to ever ignore his instructions, and with his typical smile added: ‘But the outcome was good.'”

How was the atmosphere in Beirut after the operation?

“It was really tense and people were very suspicious. People filled the street and chanted outside, people who looked like high ranking officials. Most of the stores in the area were closed. I remember getting dressed and going downstairs to send the letter I had written. From their, I went to the library and the salon, I tried to keep up my normal appearances.”

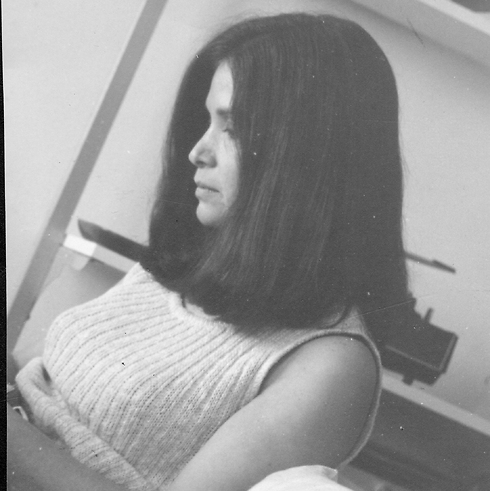

Yael during her operational years

Where you afraid?

“Not really. Now when I think back, it seems scary. It scares me that I wasn’t afraid. Maybe the fact that I was American, that I didn’t grow up like the Israelis – fearing the Arab street, it made me immune at the time. I was also stuck in my routine, doing everything to maintain the trust. When I told the landlord I was flying to Belgium, he told me he wanted to drive me to the airport so he could protect me.”

Do you remember the feeling of taking off from Beirut?

“Alongside the huge relief that I felt, I thought about the nice landlord, and my Lebanese friends who asked to protect me, and rejected any suspicion. They were all nice to my cover story, the filmmaker, but what if they knew my true identity, things would probably be different. Even now with the book set to be published, I think about the nice people living on Al Waleed Street in Lebanon, and how they would take the news, they would probably be furious.

Did them leaving you in Beirut raise any questions for you?

“It was specifically Mike, who knew me better than I know myself, who raised the issue in a conversation we had after I got back. He said he was the one who made the call to leave me in Beirut and asked me what I thought about it. I told him I thought it was a good decision. But he insisted on explaining the reasons and judgments he reached after rigorous staff work, and after seeking advice from the head of the Mossad, before they made the decision. What worried them was my personal safety, maintaining my cover story, and the possibility of retaining my cover so I could continue my missions. They believed that in order to maintain my ability to operate out of Arab countries, it was best for me to leave the scene in a relaxed and normal fashion. They left me so I wouldn’t ‘burn cover,’ so I could continue my job as a fighter. In hindsight that was the right thing to do because it worked. I didn’t burn my cover, and participated in other operations. With that said, today and I understand that I took a big risk.”

The Secret

“I didn’t speak about it for many years”

The idea for the book came from Mike Harari. Efrat Mes, who wrote the book “With Open Eyes,” with Zvi Zamir, contacted Harari during the writing process. After Zamir’s book was published, Harari asked Efrat if she was willing to write about “Spring of Youth” and the role Yael played in it. The book, “Yael- female Mossad warrior in Beirut” came about as a result.

Yael is unwilling to speak about the other operations she took part in. The book only mentions that these were bold operations, one of which earned Yael the Chief of Staff’s commendation. But Yael does talk about meeting Prime Minister Golda Meir a month after the operation in Beirut. “Zamir and Mike took me to Golda, in order to show her what a female fighter looked like,” Yael says. “She thought that everyone in the Mossad was some muscular hero. She was stunned when I entered the room, and said: ‘This little girl did all of that?’ We spoke in English. She sat me down next to her on the sofa, and when we left she hugged and kissed me.”

Only a few months after you came back to Israel your dad came to visit.

“He obviously didn’t know anything about it. This secret, which sat between me and my parents, is one of the things I struggled with most. My father came to Israel right after the Beirut operation, and I was really worried that someone would recognize me in the street. He wanted to travel with me to a bunch of places all over Israel, but I couldn’t. The office didn’t want someone who happened to be in Beirut to recognize me. I assume I was acting strangely in his eyes, and I believe he knew something was up, intuitively, but he never asked any questions. The office took him to visit military bases, and a submarine. My cover at the time was that I worked in the computer division of the Defense Ministry. I didn’t see my parents a lot during those years, and I kind of felt like I was missing out in that I couldn’t share my life with them. I often asked myself if they would be proud of me. Lately, before the book release, I spoke with family members who told me that if my parent would have known, they would have been very proud. It was good to hear that, but the question will continue to haunt me to the end of my days.”

Was it hard to keep such a main part of your life secret for so many years?

“The fact that you can’t share your life with others is one of the hardest things about being a Mossad agent. It takes a certain personality. During all those years I never had a best friend. After finishing my service I wrote a diary. Efrat Mes was the first person I spoke to openly, and who became a friend.”

What made you decide to write the book?

“It was Mike Harari’s idea. I had mixed feelings about it, I still feel like I’m doing something that is not allowed. I didn’t speak about these things for many years, even with other agents, and it also goes against policy. But Mike wanted to. It was important for him to explain “Caesarea’s” role in this big operation.”

As someone who grew up on Mata Hari and similar stories, its difficult not to ask how much is expected of female agents in terms of using their femininity for operation purposes.

“I used my femininity on several occasions, but I never used my body in order to be accepted or gain trust in the places I worked. I felt like maintaining boundaries was one of the strong points of being a woman and that was also the message I got from my superiors. I was never expected to sleep with someone on the job, the opposite was true – and even more so, that was the policy. In one instance I wanted to eat in a hotel’s dining room, and I was asked if I was alone. When I answered yes, they told me that they do not serve unaccompanied women. They feared that prostitutes would start coming into the hotel. But my femininity usually got me where I wanted to go. When I walked pass the houses of three of the targets, the guards asked me what I was doing there. I told them I lived there. They said ‘alright,’ and left me alone. They never asked me again, even in the following days, when I went to the vegetable store which was adjacent to their building. People like pretty women. This held true for the landlord in Beirut as well, but he never crossed the line, I always got very gentleman like treatment from him.”

In the collective memory of Operation Spring of Youth, most people remember Sayeret Matkal’s mission commander Ehud Barak dressing up as a woman. Does it bother you that the Mossad’s role was minimized?

“We weren’t expecting any credit; we were used to being out of sight. Personally I felt ok with it. I lived peacefully with the fact that we worked in the shadows, I wasn’t looking for public acknowledgment. It was my mission and I accomplished it. But sometimes I did ask myself why they didn’t mention us more. Mike passed away while the book was being written. He was on his deathbed when he asked Zvi Zamir to help move the book along. That’s how important it was to him.”

Do you every regret devoting your life to the Mossad? For the personal cost you had to pay.

“No. I was an active operative for 14 years, and I would have stayed longer, but I was getting physically weaker, and I had to stop. I was very proud of what I had done. I would want to do more.”

Regardless, from the book we can understand that you paid a price, realistically giving up on intimate and romantic relationships.

“Truthfully, I wasn’t all that interested in getting married. My first marriage was very difficult, and I was afraid that would happen again. But it is truth that during my years of service I never gave relationships a chance to grow. After “Spring of Youth”, I fell in love with a man I met in Brussels, and I never even thought about letting the relationship grow without Mike’s advice. I took him to meet with Mike, and Mike told me “follow your heart,” and I went – but I quickly ended that relationship too.”

Can you be an agent with a husband and kids?

“I wouldn’t have been able too. As a matter of fact, I only met my current husband, Johnny, a short while before I retired from the Mossad. It’s not by chance that this happened after I finished my role as a field agent, it was only then that I was ready for it. We met during one of my attempts to learn Hebrew in an ulpan. He was a teacher there and he “ruined” my Hebrew studies. But in all the years before, I never felt like I was missing out, quite the opposite. Those years gave my life meaning. That’s exactly what I told Mike in our first meeting: ‘I want to be worth something. I want to do something worthwhile’ – and that I have accomplished.”