The more the regime believes that its foreign adventures threaten its internal foundations, the more likely it will be to temper its behavior.

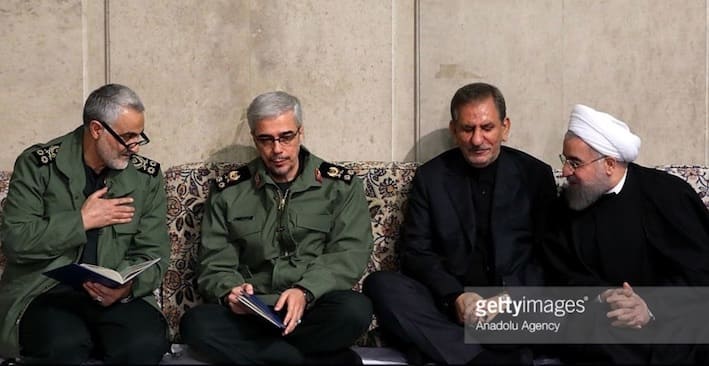

Iran’s leaders are seemingly riding high in the Middle East. They have helped secure Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Hezbollah has a stranglehold on Lebanon. The leading Shiite militias in Iraq march to their tune and have leverage over the Baghdad government. Iranian-supplied weapons, including missiles, are serving as a cheap way for the Houthis in Yemen to bleed the Saudis. Qassem Suleimani, the leader of Iran’s Quds Force, an expeditionary unit of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), appears on the front lines across the Arab world, conveying the impression that Iran and its allies cannot be defeated.

The image of Iran on the march is one the Islamic republic has sought to market and exploit. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has spoken of Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq as being part of Iran’s forward defense. His close advisor Ali Akbar Velayati, while in Lebanon in November, declared the country—along with Palestine, Syria, and Iraq—as part of the Iran-led zone of resistance.

But there is a cost to Iranian expansionism, and we are now seeing it. Iranian citizens are demonstrating across the country in large cities and smaller ones. The protests began on Dec. 28 in Mashhad, Iran’s second-largest city, and have spread throughout the country to include Qazvin, Karaj, Dorud, Qom, and Tehran. It is apparently not only the urban middle class that has taken to the streets but the lower and lower-middle classes as well. Placards criticizing corruption are rampant, and some demonstrators have even chanted death to the dictator, referring to Khamenei. Protesters have also railed against the costs of Iran’s foreign adventures: One of the earliest chants was, “Not Gaza, not Lebanon, my life for Iran.”

Economic complaints initially seemed to have driven these protests. After subsidies on staples such as bread were reduced, prices shot up—greatly affecting lower-income Iranians. A number of credit institutions failed, and many lost savings. Inflationary pressures have devalued Iran’s currency and cut into many citizens’ wages. It is true that the expected economic benefits from the nuclear deal have not been fully realized, but that can provide only part of the answer for Iran’s economic woes. The Iranian economy has long been mismanaged, and the role of the IRGC and the large religious trusts, known as bonyads, distort the Iranian economy and may affect as much as half of the country’s GDP.

None of this is to say that the Islamic republic is on its last legs—far from it. But for a regime that prides itself on control and recalls well what brought Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi down, the protesters flocking to the streets cannot be a happy sight. Some demonstrators are even chanting for a referendum—an echo of the referendum that the new regime held two months after the 1979 revolution to provide itself legitimacy.

The regime has never shied away from using force and coercion to preserve itself. Two of the presidential candidates from the 2009 election, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi—a former prime minister and a former speaker of the parliament, respectively—remain under house arrest because they challenged the results of that likely rigged vote. The regime may have been shaken by the protests in 2009, but through arrests, brutality, and efforts to atomize the opposition, it prevailed.

No doubt, one of the reasons Khamenei allowed Hassan Rouhani to win the 2013 presidential election and complete the nuclear deal was his understanding that the 2009 crackdown and subsequent economic downturn had eroded his regime’s legitimacy. It was important to restore a sense that change was possible, and when the Iranian public has a chance to express its views, it typically votes for liberalizing society at home and normalizing relations abroad.

Nevertheless, Iran is now witnessing its most severe demonstrations since 2009. The wave of protests was not sparked by election results but by economic grievances and general dissatisfaction. Even if smaller than the 2009 protests, they appear more widespread—and unlike them are being led by those in the rural provinces, which are traditionally sympathetic to the regime. The social media platform Telegram, which is widely used in Iran, spread the news about the protests and appeared to give them momentum—and, of course, now has been cut off by the regime.

So what should the United States do? In June 2009, I was serving in President Barack Obama’s administration as the secretary of state’s special advisor on Iran and was part of the decision-making process. Because we feared playing into the hands of the regime and lending credence to its claim that the demonstrations were being instigated from the outside, we adopted a low-key posture.

In retrospect, that was a mistake. We should have shined a spotlight on what the regime was doing and mobilized our allies to do the same; we should have done our best to provide news from the outside and to facilitate communication on the inside. We could have tried to do more to create social media alternatives, making it difficult for the regime to block some of these platforms.

At the time, Obama had captured the imagination of the world. He would have found it relatively easy to mobilize support for the human and political rights of the Iranian public. Obviously, President Donald Trump does not have that standing internationally and is not seen as a champion of human rights.

Still, the lesson I draw from 2009 is that the United States should not be silent. The administration should matter-of-factly, without hype, take note of the protests and call attention to the economic grievances of the demonstrations, which are surely compounded by Iran’s adventurism in the Middle East. The protestors are asking why their money is spent in Lebanon, Syria, and Gaza—and the administration should be putting out the estimates of what the Islamic republic is actually spending. On Hezbollah alone, Iran is estimated to provide more than $800 million a year—and their costs in sustaining the Assad regime come to several billion dollars.

The European Union, and especially the French and Germans, has been largely silent so far. It will not respond to Trump’s calls but should be encouraged, nonetheless, to stand up for the human rights of those engaging in peaceful protest and who are now facing a tougher crackdown from the regime.

Trump has said he wants to counter Iran’s destabilizing activities in the region. At this point, however, his administration has done very little to raise the costs to the Iranians for their regional actions. In Syria, the linchpin of Iran’s effort to expand its sphere of control, the administration does not have an anti-Iran strategy.

Ironically, the Iranian public is making it clear it is fed up with the costs of the country’s expansion in the region. Highlighting these costs could stoke the public’s dissatisfaction further. The more the Iranian regime believes that its foreign adventures may shake its foundations on the inside, the more tempered its behavior is likely to become.

Dennis Ross is the counselor and William Davidson Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute.