Threat of regional war prompted huge American deployment

As tensions escalated in the Middle East over the civil war in Syria, in April 2018 the United States deployed one of the largest naval forces to the region since the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The carrier strike group, centered on Nimitz-class nuclear-powered supercarrier USS Harry S. Truman, seven surface combatants and two submarines departed stateside for the region on April 11. They were scheduled to join a guided-missile cruiser, three guided-missile destroyers and a nuclear-powered attack submarine already in the Mediterranean to form a 15-ship-strong naval task force.

In addition, the USS Essex expeditionary strike group was slated to deploy to the area. Along with its escorts, the Essex would embark a squadron of Lockheed F-35B Lightning IIs, representing the long-awaited operational debut of the Joint Strike Fighter.

While it may be the largest U.S. naval deployment to the region since the start of the Iraq war, much of the sea power involved in that conflict deployed to the Persian Gulf. Even in the 1991 Gulf War, which involved a larger force, the carriers operated from the Gulf and the Red Sea. In actuality, the largest American naval deployment to the Mediterranean occurred 36 years ago during a war that didn’t directly involve the United States.

On June 6, 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon in response to an increasing number of provocations by the Palestinians. In some of the fiercest fighting of the modern era, the Israelis made quick of its adversaries, one of which was the military of Syria under the rule of Hafez Al Assad, father of current Syrian leader Bashar Al Assad. By June 14, Israel was laying siege to Beirut.

As Tel Aviv continued to place maximum pressure on the Lebanese capital, concerns arose in Washington and around the world of the possibility of the eruption of a larger regional war, mainly one drawing a deeper Syrian involvement. In response, the Reagan administration bolstered its presence in the region.

The next day, two more carrier battle groups, centered on USS Forrestaland USS Independence joined Kennedy and Eisenhower from the United States. The result was a 50-ship task force, with four carriers and their air wings at the core, along with a plethora of other surface combatants. This powerful juggernaut was to conduct a NATO exercise codenamed “Daily Double,” but were also ordered to prepare for additional evacuations and, possibly, rescue attempts of other Americans still in Lebanon.

Though the siege of Beirut would last until August, the situation had stabilized to Washington’s satisfaction within several days. Exercise Daily Double concluded, and Forrestal and Independence relieved Kennedyand Eisenhower of duty, sending the latter two home.

This “dream team” lasted for only days, but it represented one of the greatest assemblies of air and naval power in the post-Vietnam War era. It was certainly the most powerful concentration of carrier-based air power ever in the Mediterranean. By comparison, two carrier battle groups were deployed to the Mediterranean for the Iraq invasion in 2003.

By 1982, the carrier and its embarked air wing had improved by leaps and bounds from just a decade earlier. Apart from Forrestal, which still carried the McDonnell Douglas F-4S Phantom II, all three carriers were equipped with the Grumman F-14A Tomcat as its primary fleet-defense fighter.

By then in its second decade of service, the Tomcat had already proven to be one of the world’s deadliest dogfighters. Armed with one of the most powerful radars of its time and the long-range AIM-54 Phoenix missile, alongside shorter-range missiles and a gun, the Tomcat would prove time and again in the Middle East it was one of the region’s “top guns.” Just a year prior, two F-14s had downed two Libyan fighters over the Gulf of Sidra, an area not too far from the shores of Lebanon.

Though the air wing of the early ‘80s lacked the more sophisticated precision-strike capabilities of today, they did not lack in range or bomb-toting capability. The primary attack platform of the day was the Grumman A-6E Intruder, which had been recently upgraded with the Target Recognition Attack Multi-Sensor system, which afforded it all-weather, day-and-night attack capability.

The Intruder had a combat radius of nearly 1,000 nautical miles and could carry up to 18,000 pounds of guided and unguided ordnance. By comparison, the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet can carry 17,750 pounds of ordnance, it has a combat radius of just 390 nautical miles.

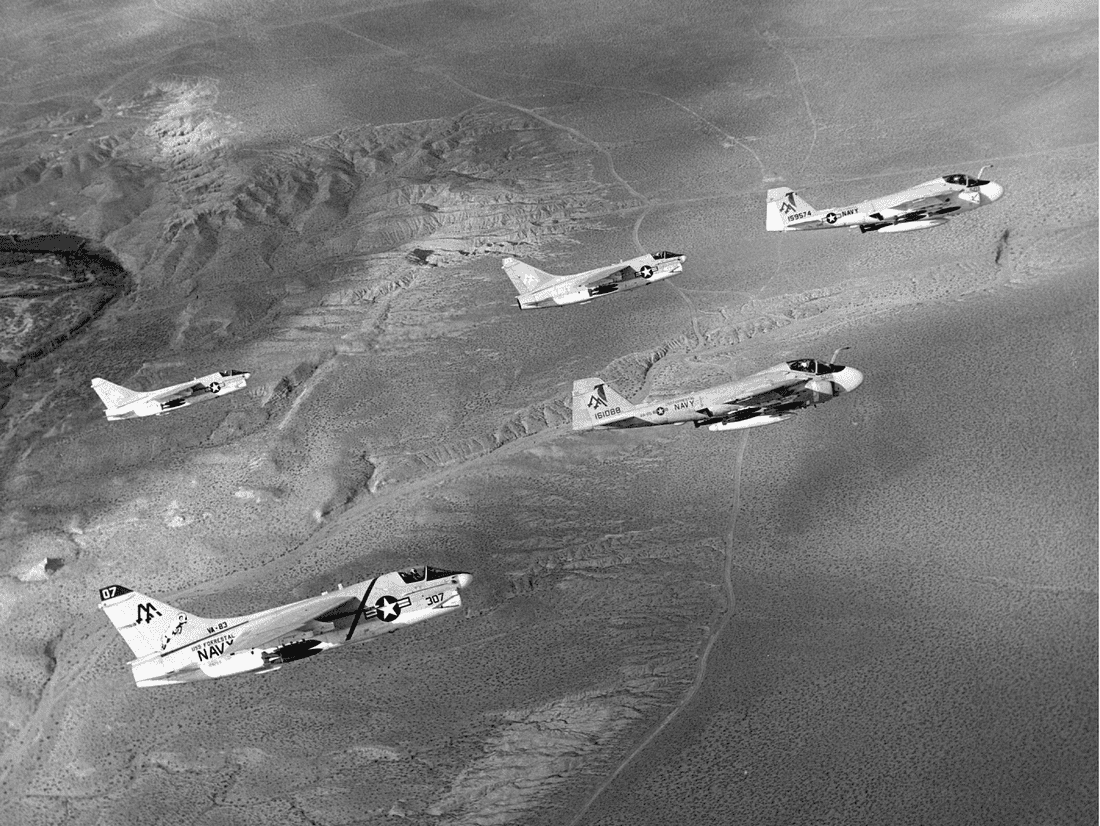

The early-‘80s air wing also had a light attack option in the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7E Corsair II, which could carry unguided and limited amounts of guided munitions. It would be gradually replaced by the new McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet during the decade, but while lacking the sophistication of the newer platform, the Corsair still had superior range, to say nothing of the Intruder.

This lack of range in both the legacy Hornet and the newer Super Hornet has been cited by analysts as problematic for the contemporary carrier air wing as it faces increasingly more capable great-power opposition in the militaries of countries such as China and Russia.

The “big three” of the ‘80s air wing were supported by the E-2C Hawkeye Airborne Early Warning plane, the EA-6B Prowler for electronic warfare, the S-3A Viking for anti-submarine warfare and the SH-3H Sea King helicopter for ASW and search-and-rescue.

Tactics, however, had yet to catch up with technology. Well into the 1980s, the U.S. Navy still employed approaches to strike warfare rooted in those used in Vietnam. Some lessons are learned only during a shooting war. The debacle the following year over Lebanon in which two Navy A-6Es were lost, one pilot killed, and another captured during an attack on Syrian targets precipitated improvements in tactics and training.

These lessons were incorporated into a new training syllabus at Strike Warfare Center, located at Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada, where air wings train extensively to prepare for deployments.

The deployment of four carrier battle groups to the region was strategically significant in 1982, as the Middle East had yet to become the focal point of U.S. foreign policy and military activity it is today. As tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union ratcheted up one last time during the Cold War, America’s focus was on defeating the Warsaw Pact in Central Europe and deterring the Soviets in the Pacific. Simultaneously, change was in the winds.

Regional conflicts, such as the Yom Kippur War of 1973, showed the United States and the USSR could come to blows in regions other than Europe or Northeast Asia. Furthermore, conflicts in key regions of the world, such as the Middle East, could still have global implications, for example, by threatening the world’s oil supply. Even today, the Syrian Civil War has created a refugee crisis that Europe has experienced great difficulty addressing.

Exercise Daily Double reflected this new reality. The maneuvers were part of a larger Reagan administration strategy to convince NATO of the importance of the Persian Gulf region to the defense of Europe against Moscow.

Finally, the Mediterranean, in many ways the cradle of Western civilization, has experienced armed conflict on a near-daily basis for centuries. From the 1970s to the end of the Cold War, the United States slowly but surely placed greater emphasis on preparing for these smaller, yet globally consequential conflicts that are far more likely to occur than any full-blown confrontation between the great powers. As a result, the United States began preparing to fight adversaries other than the Soviet Union, preparations that paid off in subsequent clashes with Libya, Iran, Iraq, Serbia, Afghanistan and, now, Syria.

As the United States mulls the possibility of greater intervention in a Syrian war directly involving the great power of Russia, the regional power of Iran, and an endless list of other state and non-state actors, a scenario is developing where it will have to figure out a means of waging war against all types of adversaries at once. It may be the Middle East, not Europe or the Asia-Pacific, where America and its allies will be faced with its most complex military challenge.