The Olympic Movement has a sense of quasi-royalty. The IOC think they are almost born to lead and rule, and that arrogance is equally as culturally negative to FIFA’s greed arrogance.

In our world, most on-the-record interviews are notably restrained affairs. Respondents are invariably fearful of deviating from the script and offending others, and have PR assistants lurking ominously close-by to ensure the “key message” comes across.

Speaking to International Centre of Sports Security (ICSS) director of integrity Chris Eaton was like ripping up this script and starting again.

“When I came in, my task was to drive us out of business,” he tells me without the hint of a smile.

“The minute something formal and efficient comes in, there’s no need for me. My objective is to see something replace the gaps we’ve filled; something with a public and private need that will look after sport and protect sport.

“My aim is to do that…and then I can go off and f****** retire.“

A veteran Australian policeman, he has made his career out of being blunt and straightforward, and not giving two hoots over who he upsets and offends.

“Yeah, of course I can sit down with you,” he chirps when I accost him in the corridor at last week’s ICSS-sponsored Securing Sport Conference in New York City. “I’m meant to be somewhere else, but that can wait.”

With the Conference focusing around the theme of corruption in sport, Eaton has been in his element, putting the world to right and making clear wrongdoing lurks in virtually every office and orifice of sports administration. Rather predictably, considering Reform Committee chief François Carrard, Presidential candidate Tokyo Sexwale and US Soccer head Sunil Gulati were among the speakers, it is the woes of FIFA which has dominated proceedings, with Eaton and other like-minded pundits queuing up to predict the impending demise of football’s world governing body if radical and immediate changes are not made.

But one snippet of his opening day speech which made an impression was the claim: “FIFA’s problems are the norm rather than the exception within International Federations”, something that fiercely contradicts the saintly proclamations of the Olympic Movement in recent months as it seeks to distant itself from any comparison.

Is this fair, I venture, although I am fairly sure about the response I will receive from the look on his face.

“The Olympic Movement has a different problem,” 63-year-old Eaton answers. “A sense of quasi-royalty. The IOC (International Olympic Committee) think they are almost born to lead and rule, and that arrogance is equally as culturally negative to FIFA’s greed arrogance.

“Remember, the IOC has only emerged fairly recently in governing body terms from its own scandal at Salt Lake City [in 1998]. So they shouldn’t point too many fingers and make themselves out to be the superior body.”

He continues: “The IOC rebuilt their values, but in a very pretentious way and the pretentious behaviour means they will never lead grassroots sports until they can become part of the grassroots culture.

“So the IOC doesn’t really have the role it pretends it has, it is really an event-management company. It exists to manage the Olympic Games. It has no direct authority, other than influence – because of the Olympic Games – on other sports federations and governing bodies.”

What about Agenda 2020, I ask, feeling the need to defend the IOC. Surely that is more than event-management?

“In broad form, yes,” Eaton concedes.

“But what was one of the the first things Thomas Bach introduced when he became President? The Autonomy Committee.

“And that’s a misreading of what’s happening in sport because autonomy and independence is up for question today. His first action should have been about getting to the heart of the problem, not survival. There is good reason for autonomy, but these good reasons have been bastardised into ineffectuality in order to protect leaders, to keep them opaque.

“His first duty should have been to set up some sort of sport transparency committee.”

I’m not sure if this is entirely fair, because, while autonomy was on the agenda at the Olympic Summit in Lausanne soon after Bach assumed the Presidency in September 2012, so were issues closer to Eaton’s heart, such as combating doping and match-fixing.

But the Aussie is on a role now. “Marius Vizer, when he stepped on his own landmine. The fact is, what Vizer said had a lot of resonance with me. Perhaps he didn’t do it the right way, but maybe we should also revisit his agenda.”

Vizer faced widespread criticism and desertion after fiercely criticising Bach and the IOC in April, and less than two months later had resigned as President of SportAccord, with the organisation now facing a battle for its very survival at this week’s Extraordinary General Meeting in Lausanne.

But, behind the scenes, many people agree with elements of Vizer’s hastily released and swiftly ignored 20-point agenda, which included the introduction of prize money for Olympic medallists, an athlete support pension fund and the setting out of clear rules, criteria and principles for IOC membership, the IOC system, the selection and addition of sports and disciplines into the Olympic programme.

Eaton believes some sort of coalition is required to link all sporting bodies, but does not know how exactly that should work. “It should not be the IOC, or the Association of National Olympic Committees or anything like that,” he says. “Something more collective and multisport.”

He adds: “The absolute success of sports competitions has brought issues of wealth which has in turn brought issues of selfishness and greed. And only a value-centred organisation could have stopped that. Clearly, at some point in FIFA, and in the IOC pre-Salt Lake City, this focus on values was lost.”

I point out how, with the exception of Brian Cookson ousting Pat McQuaid as International Cycling Union President in late 2013, there has been almost no instance of a sitting head of an Olympic sport being voted out of office rather than dying or leaving of their own accord in recent decades.

This is because there is no “internally driven refreshment of leadership,” Eaton responds. “Without that, change becomes externally driven, and that’s what happening today. If you don’t recognise external realities, you will eventually have them forced on you.”

The cataclysmic eruptions with FIFA this year, where the body’s President Sepp Blatter is currently suspended for corruption, is best explained by this, he claims, arguing that if changes are not now made, FIFA will not survive.

He points out how this has happened in other sports in the past, such as tennis, baseball, and boxing, with other organisations either emerging either from the ashes or taking over.

Far broader reforms that those envisaged by former IOC director general Carrard and his Reform Commission are therefore required.

“The worst thing FIFA can do is dwell on the Presidential Election or reforms,” Eaton says.

“It needs to holistically rebuild itself. I think there is a collective will to do this, but whether that will is in the right parts of the organisation, I don’t know.”

A broader problem, he adds, is that FIFA is just the top of football’s structure, not the leader. It has little control over Federations, leagues and clubs, although change is required at all levels.

Blunt as he is, it is perhaps no surprise Eaton has faced personal allegations of hypocrisy.

A lifelong copper since the age of 17 in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda, the 65-year-old spent 30 years in Australia before moving to Europe to spend the next 12 with Interpol, a year of which he was seconded to work on the United Nations’ “Oil for Food” programme in Iraq.

In 2010, he was employed by FIFA as a security advisor for the World Cup in South Africa, and was kept on as head of security thereafter before departing to join the Doha-based ICSS two years later.

Several of his personal emails were included in the

He sees things rather differently.

“When a raft of reforms I proposed against match-fixing failed, I saw no point in staying an FIFA, and there was an opportunity to join the ICSS, and I saw this as a chance to add some value to the ICSS, which was very good, and I’ve enjoyed it ever since.

“In 2011, I proposed a whistle-blower programme, an independent hotline, an amnesty, a witness protection and rehabilitation programme, giving everyone in football a chance. This was approved, and we gave a selected media briefing about it in November. Then the President [Blatter] killed it and referred it to the IGC (Independent Governance Commission), who never considered it.”

What do you say to people who think it’s ironic how ICSS preaches about integrity in sport, I ask, while being based in and financed by Qatar, a country more associated with problems than perhaps any other?

“But we’re not associated with Qatar 2022,” Eaton answers in a slightly riled but increasingly passionate tone. “We’re an independent and neutral organisation. The fact we are funded by Qatar is good because at least one Government is putting its hand in its pocket to do something for sport. I’d be very happy if the US Government created an independent and neutral body doing the same work. Same with the British or German Governments…

“Sitting there pointing a finger at Qatar is so puerile. I don’t care what the Sunday Times writes about my personal emails, I have never been directly influenced or controlled by anyone at the ICSS. I speak freely as a person representing the interests of ICSS in sport integrity.

“This [criticism]can border almost on racism, jealousy or insecurity. If they were English, would you be saying the same?”

Match fixing is clearly one of Eaton’s favourite areas to tackle, and he claims the involvement of criminal gangs fixing matches in sport is a worse problem than either internal corruption or doping.

“Some people are concerned about problems within governing bodies,” he says. “But most normal fans are concerned about performance on the field of play. When it gets to the point where there’s an abject cynicism about performances, and about the decisions of referee and players, that will affect a sport’s popularity.”

Match-fixing is less of a problem in the Olympics, he concedes, due to a comparative lack of money in betting. There have been allegations raised about suspicious betting in several Olympic football tournaments, but generally the problem is more about “cheating to win than corrupting to lose”.

In a general sense, it is dead rubbers which are most susceptible to fixing, Eaton believes, adding that they should be eradicated from all sport wherever possible.

He cites the popularity of sports like wrestling and boxing when he grew up in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, and how they “withered and died” because they didn’t address match fixing problems.

“The power of the fan is enormous. They don’t have a voice, so instead they just walk away from the sport.

“Sport therefore needs to engage their fans and players. Not just old guys who started out as administrators and ended up still being administrators, their dotage. Most organisations recognised years ago that you need this mix of ideas.”

Last week’s opening of a French criminal investigation into former International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) President Lamine Diack, where he is accused of accepting money as a bribe to turn a blind eye to Russian doping, shows how sporting governing bodies should not ultimately have control of any of the three broad integrity matters of corruption, doping and match fixing, he claims.

Organisations like the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) should also not be dominated by these bodies. “They have to be independent and neutral,” Eaton adds. “This cannot be achieve when the body with a vested interest involved in maintaining status quo is in control. So governing bodies should have a place but must not dominate.”

This, at least, is certainly a point accepted by others, with a WADA-led but fully independent anti-doping body proposed at last month’s Olympic Summit in Lausanne so as to reduce this supposed conflict of interest.

A good idea, on paper at least, with doubts having been expressed about how much it would cost WADA to undertake testing themselves, with a figure in the hundreds of millions of dollars thought likely.

But this all relates back to Eaton’s initial point about public and private partnerships boosting the running of sport. By this he doesn’t mean sporting “insiders” like Carrard, even if he has no direct experience in FIFA, but an external organisation or individuals with “no tie, no responsibility or accountability, no favours to give and no business to get out of it”.

Condoleezza Rice, the former United States Secretary of State who spoke impressively about her love of sport at the ICSS Conference, is cited as one possibility, although I’m not sure how well that would go down with those opposed to US interference in international sport.

“When people see sporting luminaries investigating other sporting luminaries, the natural assumption is, ‘Oh, they must be friends, they must be tied together, or from the same country or even the same town,” Eaton claims. “This will not get the public to see it as a serious examination.

“We need people of substance or gravitas, with well-respected judgements and abilities to make recommendations.”

The trouble of spending time talking to people like Eaton, I find, is that you begin to spot corruption lurking everywhere and to ignore the good that some of these organisations are doing. Listening back through the tape of our interview, I feel a pang of guilt that I have not pressed him enough on this point, so send an email, asking if anybody in sport deserves praise?

“Notably the MLB (Major League Baseball), ICC (International Cricket Council), World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association (WPBSA) and some others are fully committed and have strong anti-fixing – corruption to lose – and cheating – …to win – programmes,” is the match-fixing orientated reply. “However the problem is even these exist separately and aside from each other. There needs to be a pan-sport, pan-Government collective approach to maximise the prevention and disruption of criminal targeting of sport.”

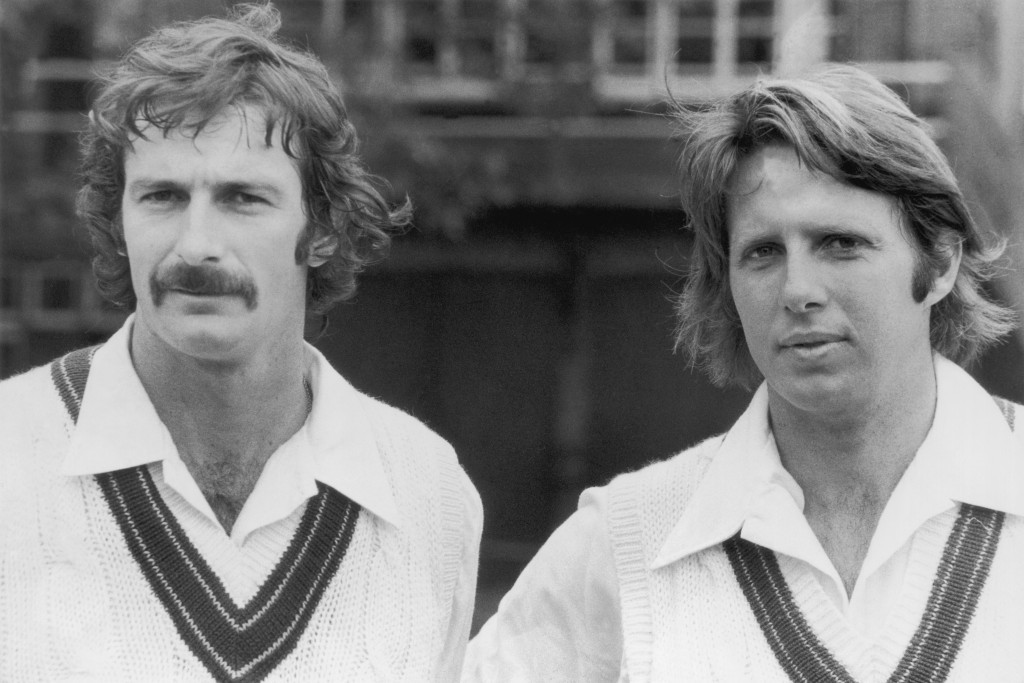

But, despite this guarded praise for the governing body, cricket is another sport Eaton believes is on the wane due to a raft of problems, particularly in its long term five-a-side Test sense. He tells me how he grew up watching great Australia teams, citing the fast bowling duo of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in the 1970s as particular heroes.

And there is something about these great galacticos of the 1970s which reminds me of Eaton, and it’s not just to do with Lillee’s similarly distinctive facial hair. Charging in again and again, launching ferocious bouncers and yorkers at the English batting establishment seems rather similar to Eaton relentlessly taking on the powers that be in sports administration.

Many may not like his style, and may not see much sense or truth in what he says, but you have to appreciate his effectiveness and necessity in an increasingly fragmented and distrusted sports movement today.