Israel has in recent years been living with a dangerous phenomenon, to which it has wrongly become accustomed, without any real debate as to its advisability. Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) are Palestinian terror organizations committed to annihilating Israel, controlling Gaza, and threatening to launch attacks at times of their choosing if Jerusalem does not act as they demand. They use Gaza’s civilian population as human shields to prevent the Israelis from hitting their military infrastructure.

In response, Jerusalem has defined its goals vis-à-vis Gaza as achieving the longest possible intervals of relative calm between major eruptions of violence; in other words, it does not challenge Hamas’s ability to attack Israel. The Israeli government regards Gaza as a de facto state where Hamas is accountable for the use of force, though from time to time, in 2019 and 2022, it preferred to address the PIJ threat directly.

Jerusalem wants Hamas sufficiently weak to be deterred from initiating armed conflict yet strong enough to force its will over any potential competitor, such as PIJ or Salafist groups. The Israelis also seek to keep Egypt on their side as a force that can and will help ensure tranquility and stability. Jerusalem desires to help the Gazan economy because it both prefers prosperous neighbors and hopes this makes Hamas more cautious about commencing hostilities. The Israelis also believe the division between Hamas in Gaza and the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank is beneficial to its interests.

In Gaza, Jerusalem plays a key role in developing the rules that determine what the parties can and cannot do. Such rules are designed to give the Israelis the ability to deter attacks, defend territory, maintain intelligence dominance, and win decisively. These rules assure Hamas that its rule over Gaza will not be challenged and that, in between the rounds of escalation, it will be allowed to continue its military buildup, as the Israelis seldom strike first, and the government’s responses to Hamas’s limited attacks are always measured and proportionate.

The flaws in such an approach are clear: it grants Hamas the ability to develop its offensive capabilities, increase its political power, and condemn Israelis—especially those living within range of the Gaza Strip—to persistent threats from Hamas terrorists.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) define victory as achieving their mission. In the context of Hamas, this is realized by inflicting the damage necessary to ensure a renewed and relatively long interval of calm until the next round. This facilitates the win-win scenarios characteristic of the last several cycles, including Operation Guardian of the Walls in May 2021. In that operation, Hamas paid a heavy price militarily in a way that restored Israeli deterrence but also achieved its strategic goals inside the Palestinian political arena, namely positioning itself as the guardian of Jerusalem and the leader of the Palestinians at the expense of Fatah. It was able to recover its military capabilities quickly and to continue threatening Israel.

A far more effective definition of victory would be to rid Israel of Hamas’s threat by disarming it, prohibiting its rearmament, and demonstrating conclusively that threatening Israel is indisputably against its interests. Achieving this goal will not be easy, but with proper preparation, it may be feasible at the appropriate time. This should be Jerusalem’s goal. It must further improve its excellent intelligence coverage of the terror groups in Gaza, improve and make optimal use of its operational capabilities, and better employ its diplomatic and legal assets. Hamas is recognized as a terror organization by the countries whose support in this matter the Israelis need, so defeating it should be seen as legitimate self-defense.

Achieving true victory also requires Jerusalem to revisit its mode of operation in Gaza. The Israelis will have to take the initiative and deny Hamas the ability to produce and develop new weapons even absent Hamas’s provocation. This must be done on a major scale and not in the limited way it is performed today. Economic pressure is one particularly effective option. Hamas’s leadership should be held accountable as long as it incites and threatens Israel and arms itself to fulfill its threats. Lasting victory also means convincing Hamas (and Egypt) that if there is no other option, Jerusalem might launch a ground operation against Hamas as well as encourage Gazans to revolt.

A Strategy to Win

A proactive and decisive strategy must be formulated and implemented to force Hamas to accept a new set of rules that will relieve Israel of this threat. Such a strategy will make the Israelis’ strength and resoluteness clear to the Palestinians. It will weaken Hamas’s political standing and send a message of deterrence to Iran, Hezbollah, and their allies. It may also aid the diplomatic process by demonstrating that armed attacks and jihad against Israel harm Palestinians, and that their conditions will improve only after they accept Israel as the Jewish state.

Jerusalem must reassess its strategy and embark on such a campaign to end permanently Hamas’s threats. It should take all necessary steps to implement this new strategy as soon as possible, especially should Hamas again attack.

What is needed is not only a change in the rules of the game but also a change in both the public discourse and in Jerusalem’s definition of victory. This new definition should include denying Hamas the ability to rearm itself so that it will be less able to reengage in violence against Israel.

After years of adhering to the rules, and after repeatedly conducting operations with limited goals, it will not be easy for an Israeli government to change the rules and the definition of victory. Avoiding these difficult decisions perpetuates the current reality of “mowing the grass,” whereby each round of escalation heavily damages Hamas’s infrastructure but fails to prevent it from rearming rapidly with more sophisticated and capable weaponry. Meanwhile, Jerusalem keeps improving its defensive and offensive capabilities to counter new threats from Hamas and other groups.

Operating under the principle of revealed preference (i.e., judging the interests of entities and individuals by their deeds, preferences, and decisions rather than their declared positions), it appears that the Israeli government prefers the option of “mowing the grass” to any alternative. This choice also reflects Jerusalem’s grasp of its limitations on the diplomatic level where any change in policy might mean increased tensions with the international community, including the United States, Egypt, and possibly other Arab states, such as Jordan and Morocco, despite their collective dislike of Hamas.

The option of “mowing the grass” seems, therefore, to be the lesser evil under current conditions. Yet it is still problematic. It allows Hamas to build its strength and leaves Israel’s population under constant threat. The question, then, is whether it is possible to create and adopt better options that would make Israeli victory clear, weaken Hamas, and diminish or even eliminate its threat to Israelis. For that to happen, it is necessary to explore what changes must occur to make a different outcome possible. These changes will need to address the military and economic spheres, the diplomatic and legal context, Jerusalem’s discourse and the rules of the game in Gaza.

Military Victory

In the military context, Israel must achieve the ability to suppress totally the capability of Hamas and the other groups to launch attacks from the Gaza Strip. Instead of counting mainly on deterrence to achieve that goal, Jerusalem should improve its already quite good intelligence coverage of Gaza so that it achieves continuous intelligence dominance. The Israeli forces would then be able to thwart most planned attacks before they are launched and eliminate Hamas operatives at any level. Today, Israel does not yet have these advanced capabilities in spite of the good coverage and the impressive improvement in producing targets in advance and within real time thanks to the implementation of interdisciplinary intelligence.

On the operational side, Jerusalem must further improve its missile defense system (the introduction of laser interception may help), but more importantly, it must gain the self-confidence to operate in a secure manner from the air, sea, and ground against the military infrastructure inside the Gaza Strip, just as it does in the areas controlled by the Palestinian Authority or in Syria. In recent years, the Israelis have developed important tools designed to bring the country closer to achieving this capability. Most important among these is the concept of intelligence-intensified warfare (LOCHAMAM in its Hebrew acronym), which is designed to mobilize and make available to soldiers on the ground all the capabilities of the intelligence community in a way that is tactically relevant to the battle in which they are engaged. Another important capability is improved protection provided to ground forces. The Israelis have made some breakthroughs in this respect since 2014 by deploying newer, more heavily armored personnel carriers in ground forces and improving anti-missile protection. The use of precisely guided munitions from the ground, air, and sea has also been improved considerably.

To convince Hamas that Israel is ready to adopt a new, more proactive, and offensive attitude, including ground operations, if necessary, Israeli forces should conduct more exercises focused on operations in Gaza involving both the regular army and reservists. Jerusalem should also embark on a campaign to prevent Hamas’s military buildup along the lines of current operations in Syria. The government should deploy forces in the area as it does occasionally in times of military escalation, conduct clandestine, deniable operations in Gaza, and use influence operations to deliver a clear message.

Diplomatic and Economic Weapons

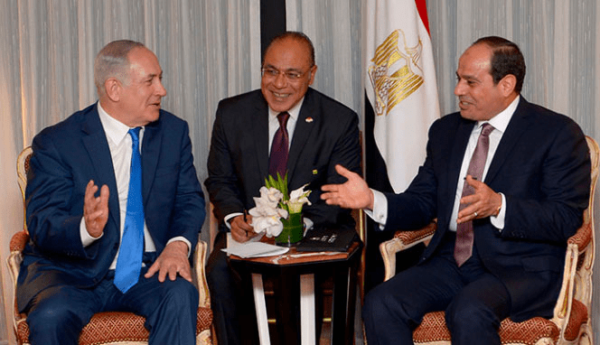

Diplomatically, Jerusalem can pressure Hamas to reconsider its military build-up, just as in the past the Israelis were able to end Sudan’s cooperation with Hamas in delivering arms to Gaza. Today, based on its tight security cooperation with Egypt, improved relations with Turkey, strong security cooperation with some of the Gulf states, and cooperation with Qatar and Jordan, Jerusalem can form a joint effort comprised of all these players to force Hamas to reassess the benefits from its efforts to arm itself.

This can complement efforts in the economic sphere. Jerusalem should condition any influx of money and economic assistance that can benefit Hamas, directly or indirectly, on the organization’s readiness to end all efforts to arm itself. This may be welcomed by many potential donors to Gaza if it is accompanied first by explanations of the severe repercussions of donating without conditions and, second, by a plan to improve living conditions in Gaza if Hamas ends all efforts to acquire arms.

The complete dependence of Hamas on foreign sources—and especially on Israel and Egypt—for keeping Gaza’s economy functioning is a key tool at the Israelis’ disposal. Using it involves conditioning the influx of funds and economic activities and benefits, such as entry of Gazan workers to Israel, on accepting this justified demand, which is a component of the Oslo accords.

These efforts have a firm legal basis since Jerusalem handed responsibility for the Gaza Strip to the Palestinians in the context of the Oslo accords wherein the Palestinians are committed not to possess weapons beyond those agreed on. The weaponry that Hamas has amassed today is far in excess of what is permitted by the accords.

The Quartet that oversees international efforts to promote peace between Israel and the Palestinians has three conditions for accepting Hamas as a legitimate player, including denouncing terrorism and accepting the agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), among them the Oslo accords. Obviously, the Israeli government has sufficient justification to deny Hamas—a U.S. and EU designated terror organization that boasts of its success in arming itself to kill Israelis indiscriminately—possession of such weapons to use against Israelis and the use of them in a manner to threaten Israel’s security. Therefore, Jerusalem has the obligation to take harsh steps to force Hamas to disarm and to deny it the capacity to rearm itself. The Israelis should be able to count on the support of every country and organization that recognizes Hamas’s status as a terror group.

Changing the Rules

Advancing these demands on Hamas and adopting this new policy regarding threats from the Gaza Strip, though justified and feasible, require Jerusalem to revisit some of the rules of the game and change the discourse about Gaza in Israeli society. For example, the rule stipulating that the Israelis will not take the initiative and will content themselves with retaliation needs to be reconsidered. If the Israel government wants to force Hamas to disarm or to stop arming itself, it should be able to operate on its own initiative and at the time and place it chooses, so that, instead of limited military action against arms production facilities, it could hit vital locations used for arms production or storage as they are discovered. Under current rules, Hamas may learn in advance when its facilities are in danger and make the necessary arrangements to minimize damage, knowing it can expect only a minimal attack. This allows Hamas to maintain weapons procurement and production between attacks.

Operation Guardian of the Walls is a notable example of how self-defeating this rule is. For several days before the operation began, Hamas threatened to launch rockets and made the necessary preparations to attack. Had Jerusalem known about these concrete preparations, it could have prevented the rocket launches and made Hamas pay a much heavier price for its intent. Had the Israelis taken the initiative and hit Hamas’s infrastructure in advance, the government’s actions would have been well within the confines of the law of armed conflict, not only because Hamas is a designated terror organization but because it was clear Hamas was planning to attack Israel. This is in keeping with Article 51 of the U.N. charter:

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations.

Such intent is sufficient cause, and the Israeli government is legally allowed to act preemptively against a planned armed attack on its citizens. In operation Breaking Dawn, the Israelis acted to foil a planned attack in advance in a perfectly legal manner.

The second rule described above—Israeli governments’ choice to refrain from enforcing long-term sanctions or pressure the Gazan economy to prevent Hamas from arming itself—should also be reconsidered. Because Hamas’s need to provide for Gaza’s inhabitants is one of its principal burdens, economic restraints have an immediate impact on its behavior. Instead of using them only as retaliation in the aftermath of attacks against Israel, they can be leveraged effectively to prevent Hamas from arming itself. The same is true of the economic measures Jerusalem takes against Hamas to encourage it to refrain from launching rockets and to commit to longer periods of quiet. These measures could and should be conditioned on Hamas’s commitment to stop arming itself and eventually disarm. These actions should also depend on Hamas’s readiness to move ahead on the issue of detainees held in Gaza and the corpses of two Israeli soldiers it holds.

Regarding the rule granting immunity to the upper echelon of Hamas’s leaders, the Israelis should make clear that as long as Hamas continues to behave as a terrorist organization with no separation between the political and military wings, and as long as it arms itself, its political leadership is a legitimate target, and not merely in the context of a high-intensity confrontation.

An additional rule, according to which Jerusalem allows Hamas to operate against the country from other areas without risking its assets in Gaza, must also be reconsidered. This was the case after Hamas launched rockets from Lebanon towards Israel in April 2023, and the Israeli response focused on Hamas’s infrastructure in Gaza. This rule leaves Hamas unrestrained in the West Bank and in Jerusalem. In recent years, the Israelis managed to thwart most of Hamas’s planned attacks from areas controlled by the Palestinian Authority or Jerusalem. There is no guarantee these successes will continue forever, so deterring Hamas from operating in other areas while its headquarters are in Gaza is necessary. The ongoing effort to convince Turkey to expel from its territory Hamas’s offices overseeing terror operations in the West Bank and Jerusalem can serve as an example of what can be done regarding Gaza. If Hamas knows that conducting terror operations from areas controlled by the Palestinian Authority and from Jerusalem is costly, it might take this into consideration.

Similarly, regarding inaction on Hamas’s incitement: Jerusalem should seek to expose Hamas messaging to justify steps necessary to prevent it from arming and to disarm it. Obviously, an organization that calls publicly for the murder of Israeli citizens and for the destruction of the state of Israel should not be allowed to arm itself as Hamas does.

The same thinking applies concerning the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The Israeli government treats this organization courteously despite its harmful actions because it believes UNRWA contributes to ensuring calm among Gaza’s population and helps improve living conditions in the strip. This is understandable as short-term logic, but if Jerusalem wishes to change the situation in Gaza for the long run, it must adopt a policy that recognizes UNRWA as part of the problem and not part of the solution. The refugee question should not be treated in a way that perpetuates the problem, which is exactly what UNRWA is designed to do. At a very minimum, the Israelis must insist that UNRWA removes from its textbooks any indoctrination and incitement of hate. It should also disengage from and condemn all employees, especially teachers, who are Hamas members or have openly supported attacks against Israel. The broader goal should be UNRWA’s disbandment. The treatment of refugees should be remanded to the agency responsible for providing services to all other refugees worldwide, namely, the U.N. High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), which defines refugees very differently and focuses on taking care of people in need rather than on political agitation.

Revisiting the rule according to which Jerusalem remains tacitly committed to not ending Hamas rule in Gaza is key for changing the dynamics of this conflict. As long as Hamas knows that the Israelis will not attempt to uproot it from Gaza, it can continue arming itself and conducting periodic attacks knowing the price it will pay may be heavy—especially if Jerusalem changes the other rules mentioned—but not existential.

History teaches that even though Western powers including the United States and Israel try to avoid overreacting to enemy provocation, an enemy’s own drastic actions may provoke a dramatic and decisive reaction. Israel’s two wars in Lebanon as well as operation “Defensive Shield” (2002) are examples of this dynamic. Clarifying this as among Israel’s viable options may not only deter Hamas and make it easier to persuade it to stop arming itself but may, also, prompt Egypt to pressure Hamas further and tighten its control of arms smuggling routes. Egypt is always eager to avoid any decisive Israeli operation that could undermine its own stability.

Unseating Hamas would not necessarily require a ground operation. Much of the work can be accomplished via stand-off capabilities, but convincing Hamas and Egypt that such an option is feasible requires a willingness to consider seriously and then prepare for a ground operation. Most of that operation could focus on the less populated areas and on the Philadelphi corridor between Egypt and Gaza. Still, some of it may occur in densely populated neighborhoods.

The one rule that should not be revisited is Jerusalem’s commitment to international law and its efforts to minimize collateral damage. This is not an impediment to achieving the goals the government should set; on the contrary, it confirms that the Israeli government occupies the moral high ground. This in itself cannot guarantee any softening of the international criticism such Israeli actions would spark, but it is extremely important for Israelis to know they are doing the right thing.

Hamas’s Threat

On top of all of that, achieving the goal of preventing Hamas from arming itself or of convincing it to disarm requires a change in Israel’s discourse on relations with Gaza. First, there must be an understanding that Hamas’s threat is strategic and thus worth the effort required to remove it. Though Hamas does not pose as great a threat as Iran or Hezbollah, its readiness to use force and the frequency of its attacks against Israel are much greater and, therefore, render it a strategic problem and not simply a nuisance. As long as many Israelis consider Hamas’s threat a chronic problem of limited importance because other problems are more demanding, the government will not be able to build the necessary public support for such an operation. Second the attitude to risking soldiers’ lives in a ground operation must change, as mentioned before, to convince Hamas that a ground operation is a viable threat. The strategy advocating Hamas’s rule over Gaza as an asset for Israel in the wider context of the Palestinian problem must also be reevaluated.

Achieving this requires sustained efforts to persuade the public by making use of the strategies described in this paper. The political class in Israel must deal with the matter, and so must civil society organizations and civilians at large. The Israel Victory Project (IVP) and the Israel Victory lobby in the Knesset, which are bipartisan, are well placed to lead this effort. Civil society organizations like HaBitchonistim can help as well. Yet these groups must be complemented by popular movements with greater civil society participation from the area around Gaza. Because Israel faces myriad threats and challenges, attention spans for a specific issue are short-lived and fail to alter permanently the conversation.

Conclusion

A proactive and decisive strategy must be formulated and implemented that will eventually force Hamas to accept a new set of rules that will rid Israel of the threat represented by Hamas-controlled Gaza. Such a strategy will also make Israel’s strength and resoluteness clear to the Palestinians, weaken Hamas’s political standing, and send a clear signal of deterrence to Iran, Hezbollah, and their allies. Eventually, it may also aid the diplomatic process by demonstrating that armed attacks and jihad against Israel harm Palestinians and that their conditions will improve only after they accept Israel as a Jewish state. It is time to begin the discussion regarding the details of such a strategy.

Brig. Gen. (Res) Yossi Kuperwasser is an Israeli intelligence and security expert. Formerly, Kuperwasser served as the head of the research division in the Israel Defence Force Military Intelligence division and Director General of the Israel Ministry of Strategic Affairs. Kuperwasser is currently a Head of the Israeli Intelligence Methodology Research Institute and a Senior Project Manager at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs specializing in the security dimensions of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.