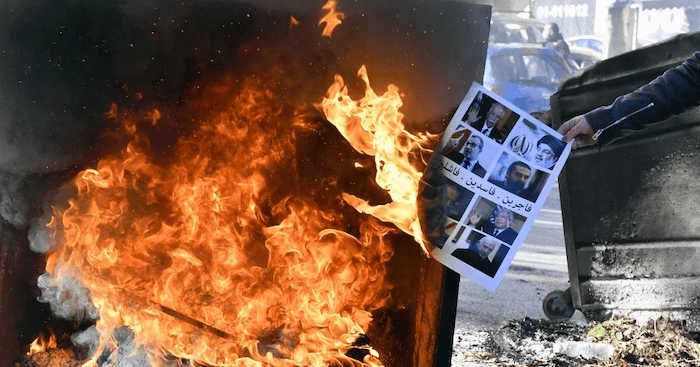

A Lebanese woman burns a poster bearing portraits of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and other politicians with Arabic words that read, “You are against achieving justice,” during a protest Monday in front of the Justice Palace in Beirut, Lebanon. Families and relatives of victims of the Beirut port explosion rallied to support the judge investigating the blast after he was forced to suspend his work.

BEIRUT, Lebanon, Jan. 21 (UPI) — Lebanon’s financial collapse, which has pushed large segments of the population into poverty, has also seen growing anger against the powerful Hezbollah, with more voices openly blaming it for the ongoing crisis and for its allegiance to Iran.

Hezbollah’s attempts to distinguish itself from the ruling corrupt political class, counting on its reputation as a resistance group that forced the withdrawal of Israeli occupying forces from south Lebanon in 2000 and battled the Islamic State in Syria, are no longer convincing to many, even to once loyal supporters.

The group’s growing dominance in internal politics, engagement in regional wars and in thwarting the 2019 popular uprising is tarnishing its image as the nation’s defender, critics say.

With a freezing winter, a continued 22-hour-a-day power cut, lack of diesel fuel and medicines coupled with exorbitant food prices, priorities are shifting to feeding the family, keeping warm, securing medical treatment or simply making ends meet.

The poverty rate has nearly doubled — from 42% in 2019 to 82% in 2021, according to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. Over two years, the national currency has lost 90% of its value while the country witnesses a dramatic collapse in basic services, an unemployment surge and closure of businesses.

Not spared from the hardship, complaints within Hezbollah’s own community are not hidden anymore.

“More and more people are expressing their discontent openly,” said a Shiite woman, in her 60s from the Baalbeck region, a Hezbollah stronghold in eastern Lebanon with the highest number of the group’s fighters killed in the Syria war. “They live day by day and are busy securing the basic things, like bread and diesel fuel.”

Freezing temperatures and snowstorms have kept the Baalbeck inhabitants indoors, barely leaving their homes to buy food. “To spare on the costly diesel fuel, they use only one sobia [heater]in one room of the house, usually the kitchen, where they sleep, eat and spend the day,” she said.

The fuel that Hezbollah brought from Iran via Syria at the peak of the fuel crisis last summer has run out. Such shipments have stopped, and Hezbollah charitable organizations are not providing services as before, according to the woman, who spoke to UPI on condition of anonymity.

“With the overall deteriorating economic conditions, people are speaking out, asking where Hezbollah chief [Seyyed Hassan Nasrallah] is taking us and for what?” she said. “We are ready to fight Israel and support the resistance, but why are we engaging in wars in Syria and Yemen while we are dying of hunger?”

‘You kept silent’

Brig. Gen. Hisham Jaber, head of Middle East Center for Studies and Public Relations who was once close to Hezbollah and a staunch defender of its anti-Israel resistance, confirmed a growing dismay among the group’s supporters in its main strongholds in southern Lebanon and the eastern Bekaa region.

“Yes, yes, yes…Today, Hezbollah has lost lots of its popular support,” Jaber told UPI. “People consider that Hezbollah is part of this political class which led the country to this [collapsing]point, saying, ‘You did not steal, but you kept silent on the thieves and covered up for them.’ Hezbollah cannot deny that.”

He argued that Hezbollah is “not aware of the danger” facing it and asked whether “it is political stupidity” or because it is “implementing orders from Iran.”

Hezbollah, which has been armed and financed by Tehran since it was founded by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard following the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, emerged as a powerful force over the years. In the past decade, it helped Iran extend its influence and power in the region, engaging in the Syria war and supporting the Iran-aligned Houthi rebels in the Yemen strife.

Jaber said Hezbollah still receives some $500 million a year from Iran, which has its own political interests in the region and is holding onto the group as an important card.

“This is very natural, but are the people [Lebanese] accepting this? No, they are not,” he said.

Hezbollah officials justify their groups’ reluctance to help fight corruption in the country by saying they fear a fallout with their allies, who are accused and blamed for the widespread corruption.

“They fear that this could lead to a big, bloody conflict. Their phobia of ending up involved in a [sectarian]strife is making them benefit from this corrupt political class,” Jaber said, warning that anti-Hezbollah sentiment is “growing like a snowball.”

Iran’s ‘occupation’

Such exasperation with Hezbollah was translated last week with the formation of a new front targeting Iran directly.

The National Council to Lift the Iranian Occupation of Lebanon was established by some 200 political figures, including former ministers and parliamentarians known for their opposition of Iran and Hezbollah, intellectuals and key civil society figures.

Ahmad Fatfat, head of the council and former minister, said their goal was to end Iran’s “occupation,” break free from Hezbollah’s armed dominance and restore Lebanon’s sovereignty.

“There is occupation by proxy… Even if Iran does not have boots on the ground, Hezbollah exists with 150,000 missiles and 100,000 fighters threatening the country from inside,” Fatfat told UPI, recalling how Iran bragged about its control of four Arab capitals, including Beirut.

He said the problem is about Hezbollah’s “illegal weapons” and practices that obstruct the parliament or Cabinet meetings to impose its conditions and “force the others to do what it wants.”

He was mainly referring to the election of Hezbollah’s powerful Christian ally, former Army commander Gen. Michel Aoun, as president in October 2016 after the post remained vacant for 29 months. Hezbollah also turned against former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, sending hundreds of its fighters clad in black to deploy in the streets of Beirut to force his ouster in 2011.

The party was also accused of being behind the 2005 assassination of Rafik Hariri, Saad’s father and former prime minister, and 11 other politicians, journalists and security officials; accusations that Hezbollah denied.

Fatfat said adopting reforms and fighting corruption are necessary to get out of the current financial crisis.

“But how can you rebuild the state with the presence of illegal weapons that covered for all the corruption over the years?” he said, blaming Hezbollah for the country’s collapse that started in 2011 when the militant group sent its fighters to Syria to fight along President Bashar al-Assad, tightened its grip on Lebanon and pushed away its traditional political and financial backers, the rich Arab Gulf countries.

Fatfat, who stressed that the new council includes Christian and Muslim members, including Shiites, believes that the Lebanese are more aware of the need to get rid of “Iran’s occupation,” as they did with the French mandate in 1943, Israeli occupation in 2000 and Syrian military presence in 2005.

But targeting the heavily armed Hezbollah in a country with a multi-confessional system, could backfire.

“Hezbollah will well use such attempts to confirm that it is facing big conspiracies and thus reassemble the Shiites around it,” Amin Kammourieh, a journalist and an independent political analyst, told UPI.

Kammourieh said that despite the growing discontent and daring voices criticizing Hezbollah, there is still no other alternative for the Shiites and no “steady force on the ground to face it.”

Jaber warned that any movement against Hezbollah and Iran from the other communities will only make the Shiites “withdraw into their own cocoon” and defend the militant group.

“This will be a mistake,” said Jaber, who is a Shiite. “If they feel that they are threatened by outside forces or from other [Lebanese] sects, it will be impossible to oppose them,” and anti-Hezbollah Shiite opponents will lose.

The change will only come from the emergence of a third force from within the Shiite community, which is currently dominated by Hezbollah and its Amal Movement ally, he said.