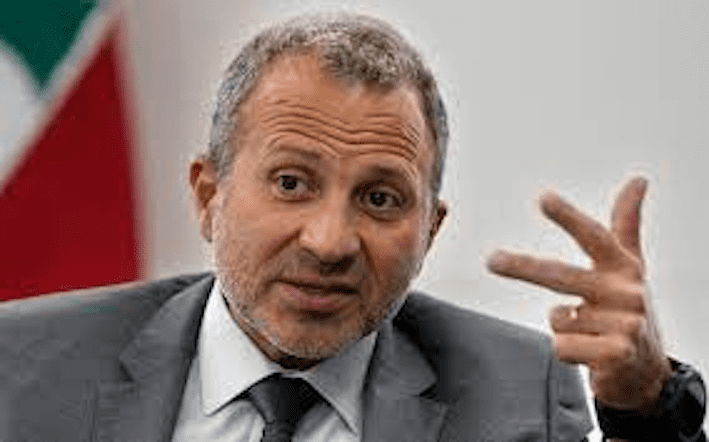

It has been an uneasy three weeks for Gebran Bassil, since his father in law Michel Aoun left Lebanon’s presidency. Bassil, who had excelled in coattail politics—riding the coattails of others more powerful than he—suddenly discovered that he had no coattails to ride. Aoun is no longer in a position of authority to block government decisions and increase Bassil’s leverage in internal disputes over governmental matters; and Hezbollah, with whom Aoun and Bassil built a political alliance in 2006, has made it clear that it would not support him today in the one endeavor that matters most to Bassil, namely succeeding Aoun as president.

By most accounts, Bassil and Hezbollah parted ways on the presidency several weeks ago, at a meeting between Bassil and the party’s secretary general, Hassan Nasrallah. Reportedly, Nasrallah asked Bassil to support the candidate that Hezbollah appears to favor, Suleiman Franjieh. Bassil is said to have refused and to have asked that Hezbollah back him instead. Since then, there has been little progress among Lebanon’s political forces to find a replacement for Aoun, leaving the country in yet another debilitating institutional deadlock.

What has been particularly evident, however, is Bassil’s inability to read the situation properly. All his hopes rested on the fact that, with Aoun in office and Hezbollah as his ally, he had enough cards to be elected president. It never dawned on him that the highly contentious six years of Aoun’s presidency, when the Aounists alienated most of the leading figures in Lebanon’s political cartel, would push Hezbollah to opt for a different path. With economic conditions having deteriorated in the past three years, the last thing the party wanted to manage was another presidential term characterized by incessant political schisms.

The Aounists have long portrayed themselves as the sole force standing against the corrupt postwar cartel. Their main bugbear has been the speaker of parliament, Nabih Berri, a leading light of the political class. There is no doubt that this cartel has led Lebanon to financial ruin. But it’s equally true that Aoun and Bassil never sought to fight the cartel, but instead pined to become influential members of it—benefiting from its patronage and corruption networks, while using their sham maverick status as a means of rallying supporters.

Above all, both Aoun and Bassil always had their eye on the presidency. Back when he headed a military government in 1988–1990, Aoun had declared a “war of liberation” against Syrian forces in Lebanon, before agreeing that parliamentarians attend a conference in Taif, Saudi Arabia, to end the Lebanese conflict. When the parliamentarians came back with a constitutional agreement, but otherwise failed to make Aoun president, he rejected Taif and within months had launched another war, this time against the Lebanese Forces militia. However, during his eleven years of exile in France, the presidency never left Aoun’s mind.

Aoun fulfilled this ambition after his return to Lebanon in 2005, following the Syrian withdrawal. He did so by entering into an alliance with Hezbollah, believing the party would eventually force the political class to elect him president. His gamble worked. Hezbollah realized that by supporting a Maronite Christian with communal popularity, it could both divide the forces that had opposed Syria in 2005 and guarantee cross-sectarian cover for itself.

Bassil learned that lesson well, but presumed too much that the influence he enjoyed over his father in law could carry over to Hezbollah. While the party seeks to maintain ties with the Aounists—indeed it was instrumental in giving them votes in parliamentary elections last May that allowed Bassil to maintain a significant legislative bloc—there are red lines. The party does not care for Bassil’s animosity toward Berri, a fellow Shia, and will not divide Shia ranks to satisfy Bassil’s presidential fantasies. That Bassil cannot see this only highlights his hubris.

If Hezbollah wants Franjieh as president, it is possible that it could scrounge up the 64 votes necessary to give him a majority in a second round of voting in parliament. However, that would require two things: that Walid Jumblatt’s bloc vote for him, and that some members of the Aounist bloc, and perhaps some members of the change bloc that emerged from the 2019 uprising, also do so. While Jumblatt is likely to go along with Franjieh if momentum builds up to elect him, at this moment in time the 64 votes remain elusive. That is why Hezbollah has not declared openly for Franjieh, fearing that it could lead to a break with Bassil, but also close off avenues of compromise over alternative candidates.

As the presidency is held by a Maronite Christian, having the support of a large Maronite bloc (Bassil leads one, while the rival Lebanese Forces control another) is seen as a requirement to give a new president legitimacy among his coreligionists. Bassil believes that any candidate that Hezbollah chooses, including Franjieh, would need his backing, since the Lebanese Forces are unlikely to vote in favor of someone the party endorses. Therefore, his aim is to impose enough conditions on that candidate to guarantee his sway over a new administration and government, thereby preparing for his own election in six years’ time.

However, no president wants to begin his term under Bassil’s thumb, and that is certainly true of Franjieh. Hezbollah, too, must know that such an arrangement would only guarantee continued domestic discord. At a time when the party’s base is suffering from the repercussions of economic stalemate in a country whose finances have collapsed, when Hezbollah sees its main regional sponsor, Iran, facing a serious and durable domestic uprising, and when a rightwing government will soon take office in Israel, Nasrallah does not want to have to deal with the distraction of sterile political disputations at home.

The most probable options at this stage are that Hezbollah will see whether it can build momentum behind Franjieh. This would involve waiting for a signal that Saudi Arabia has no problems with him, which could push Jumblatt and opponents of Hezbollah to shift their position on Franjieh. If that were to happen, Hezbollah might declare publicly for him and try to build a coalition to get Franjieh elected, with or without the major Christian blocs’ support.

A second option would be for the party to conclude that Franjieh is unable to secure a sufficient number of the 64 votes he needs to win, therefore that it is best to look for another candidate around which a consensus can be reached. In that case, the prospects of the army commander, Joseph Aoun, might rise, given that he could win support from a wider coalition of forces than Franjieh, and almost certainly would benefit from regional and international approval. Yet that is precisely what bothers Hezbollah. As Nasrallah made clear in a recent speech, Hezbollah wants a president who will not make any deals at the party’s expense, so it remains wary of anyone who has the connections to act independently of the party.

If Hezbollah rules Aoun out, the search will be on for a third candidate acceptable to all, but with one major caveat. Anyone from outside the political class would arrive with legitimacy problems, therefore would need to gain the support of a major Christian bloc. As Hezbollah is the leading elector, it would want that bloc to be made up of the Aounists and their allies. In other words, the candidate would probably have to bow to Bassil’s conditions. Yet all that would do is bring us back to square-one, since most members of the political class, Berri above all, do not want Bassil to have any influence over a new president. Nor would Hezbollah itself be overly comfortable dealing with a candidate they don’t know.

So, for better or worse, realistically we are down to two candidates, Franjieh and Joseph Aoun. What is strange about this election is that Hezbollah is not in a position to ignore the messy bargaining around who will become head of state. It remains unclear whether Franjieh has the votes to make it to the presidency, and it’s also uncertain whether Hezbollah will want to go so far as to prevent Aoun from being elected. This provides a useful lesson for all those who argue that Lebanon is Hezbollah and Hezbollah is Lebanon. Sectarian politics are rarely so simple.