(First published in Newlines, Metransparent published Frederic C. Hof’s « warning » on December 29, 2021. We thought it was a good time for a « reprint »!)

*

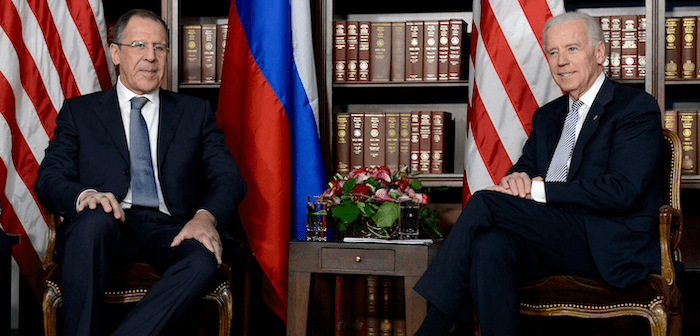

Given past U.S. failures to take on the Assad regime, Moscow’s and Beijing’s plans may well hinge on how Biden next acts in the Levant

For over a decade the United States has struggled and often failed to devise policies limiting the carnage and its international consequences wrought by a Syrian crime family, the mayhem facilitated and magnified by external supporters determined to keep a valued client in business. Internationally, the biggest and most dangerous consequence of past policy failures in Syria is the conclusion drawn by Washington’s adversaries that America’s military might is neutered by its lack of confidence and insufficiency of will. Russia threatens Ukraine and China menaces Taiwan. The belief here is that they do so with Syria, and the American performance there, very much in mind. The disorderly departure from Kabul may have been an exclamation point of sorts, but it was probably seen in Beijing and Moscow as a continuation of what they have often witnessed in Syria.

For the Biden administration much of 2021 has been spent, in the context of Syria, reviewing Washington’s past performance and assessing current policy options. This is as it should be for a new administration. Although Syria’s suffering and the bloody-minded kleptocracy of an Assad narco-regime have not abated, the Biden administration thankfully was not confronted early on with a chemical atrocity or all-out air assaults on the remaining hospitals and schools in rebel-controlled areas. A rhetoric-only response by the administration to such abominations would have further emboldened adversaries in areas they target far beyond the Levant.

The result of the review appears to be a modest policy emphasizing ongoing humanitarian aid for needy Syrians and recommitment to the goal of eventual full accountability for war crimes and crimes against humanity. In northeastern Syria, U.S. troops will remain in a supporting role to ensure that the so-called Islamic State group does not resurrect itself via insurgency. Support for the United Nations’ effort to bring about a peaceful political resolution to Syria’s armed conflict is also pledged, and the refusal of Washington to endorse reconstruction funding flowing through the regime is upheld. Moves by some Arab countries to try to normalize relations with the chronically abnormal Assad regime will, it is said, receive neither U.S. support nor encouragement.

Taken together, these policy elements would seem to indicate ongoing U.S. reluctance to accept Russia’s argument that its client has won the Syrian conflict on the battlefield and that therefore the West should accept reality and pay for Syria’s physical reconstruction. They also reflect a minimalist public articulation of policy, one silent on overall national security objectives and mute on a strategy to achieve them, a tone perhaps instructed in part by public weariness with the situation in Syria and the administration’s desire to focus its foreign policy efforts elsewhere.

Yet some critics of the administration’s stated approach toward Syria see creeping normalization with the Assad regime as the real goal. They suspect that President Joe Biden’s desire to renew the nuclear deal with Iran will, in the minds of some administration officials, dictate concessions to Iran on Syria, where its client facilitates Tehran’s grip on Lebanon via Hezbollah. Critics cite as a precedent former President Barack Obama’s reported 2014 letter to Iran’s supreme leader assuring him that U.S. military action in Syria would not be directed at his client.

Critics also note that a policy not encouraging Arab normalization with a drug-running war criminal is not the same thing as opposing it. Indeed, they see U.S. endorsement of a complicated scheme to provide Lebanon with electricity through Syrian transmission facilities as a green light to Arab states to make their own arrangements with Damascus.

Critics also point out that, notwithstanding former President Donald Trump’s personal unsteadiness on Syria, the previous administration had an objective of political transition (rooted in U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254) and a strategy aimed (among other things) at trying to weaken Iran’s grip on Syria. They now sense that some administration officials wish to drop political transition as an objective on the grounds that it has not, after the passage of a decade, happened — that Iranian and Russian determination to preserve the regime has prevailed. Yet surely some in the administration — perhaps the president himself — understand there is no deadline or expiration date beyond which efforts to unseat a mass murderer must cease. There is no statute of limitations protecting war criminals. There is no reason — urgent or otherwise — for Washington to accept the judgment of Moscow and Tehran that their miserable client has prevailed in the struggle for Syria.

Finally, critics note the Trump administration had a policy of responding militarily to the Assad regime’s large-scale chemical attacks, responses very modest in scope but sufficient to disprove the thesis that U.S. military strikes would lead to invasion, occupation and perhaps World War III. The Biden administration has not, at least publicly, reiterated its predecessor’s practice as set policy.

Yet the hope here is that the Biden administration’s public articulation of Syria policy does not reflect the full extent of its internal deliberations and decisions. After all, influential senior officials such as Secretary of State Antony Blinken and the Agency for International Development Administrator Samantha Power have publicly bemoaned past policy failures. Perhaps a minimalist public stance masks something more substantial internally. Ideally the administration recognizes the connection between how adversaries evaluate the performance of the U.S. in Syria and their expectations of America’s performance elsewhere — the link between perceived weakness in Syria and dangerous conclusions drawn from it by China and Russia.

Perhaps the administration does indeed remain committed to the political transition goals articulated by the June 2012 Final Communique of the Action Group on Syria and Resolution 2254. After all, to drop the objective of Syria’s eventual political transition from criminality to legitimacy would be to accept gratuitously the triumph of the former and to sacrifice needlessly the latter. Yes, Bashar al-Assad and his entourage remain in place. But they also personify political illegitimacy. Middle East experts in the Kremlin know this all too well, which is why they crave Western and Arab normalization with and reconstruction support for their troublesome and corruptly incompetent client.

Perhaps the administration has privately rebuked the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for its naively ill-considered move to normalize relations with Assad. Do leaders in Abu Dhabi truly believe they can persuade the regime to stop leaning on Tehran for its survival? Is the UAE about to secure the release of some 100,000 detainees from Assad’s torture chambers as the price for its doing business with mass murderers? Is reconciling with Assad part of the Emirates’ new approach to Tehran? The U.S. rightly values its relationship with the UAE, but nothing should prevent the administration from protesting a useless approach to Assad as a profoundly unfriendly act and warning of unpleasant consequences (sanctions and others) if it persists.

Perhaps the country that accomplished the 1948 Berlin airlift is now planning the 2022 ground lift of essential humanitarian aid to needy Syrians if Moscow uses its Security Council veto to shut down the crossing point for U.N. assistance flowing from Turkey. That veto could come in July 2022. An alternative to a U.N. system that channels cash to the Assad entourage is urgently needed in any event.

It may be that the administration has quietly warned Moscow that a renewal of mass murder by its client — whether by chemicals or other means — will not go unanswered militarily by the U.S. Showing that we mean business in Syria — that “Never Again” means “Never Again” — would help restore U.S. credibility around the globe. Giving the warning might, on its own, suffice to prevent the worst from happening. Yet, as demonstrated by the red line episode of 2013, bluffing is dangerously destabilizing when called. Assad’s addiction to mass homicide has roiled both his neighborhood and Western Europe. It has made Syria fertile ground for terrorists whose methods mirror his own. Washington’s coupling of soaring rhetoric with studied inaction in its responses to these outrages cast substantial doubt on its seriousness, thereby generating instability globally. This most dangerous of unintended consequences cannot now be undone by deemphasis on and distance from the scene of past policy failures. Lessons learned by our adversaries will not be unlearned so effortlessly.

Indeed, one knowledgeable observer — Ambassador James Jeffrey — argues that Syria belongs in the same category as Ukraine and Taiwan as a place where adversaries seek to undo forever the ability of the U.S. to keep the peace globally while protecting its interests and those of its allies. One hopes the administration is giving serious thought to Jeffrey’s proposition. When 51 State Department diplomats in 2015 urged the administration to respond militarily to Assad’s depredations against defenseless civilians, they were not counseling mindless militarism. They could see the destabilizing global consequences of American inaction in Syria; they saw what happened to Crimea months after the red line fiasco.

During the late summer of 2013, then-Vice President Biden was reportedly one of the senior officials counseling the president not to bluff. He was right then. He probably understands now the negative global consequences of ignoring good advice on Syria. If today he hopes to be taken seriously by China and Russia, he should take seriously the challenges presented by Syria to America’s reputation and credibility. It is not, to be sure, our geopolitical arena of choice. But we will be measured there by our adversaries, like it or not. The last thing we would want to do would be to communicate — unintentionally but recklessly — indifference, passivity, resignation and weakness to adversaries seeing and using Syria as a laboratory for measuring U.S. resolve globally. Surely this possibility weighs on the president and his key advisers.