A lot is happening in Syria’s Suwayda Governorate, but Damascus still remains the dominant outside actor.

The southern Syrian district of Suwayda, with its Druze majority, has seen important developments in the past month. Local armed factions eliminated the Quwwat al-Fajr, or Forces of Dawn, militia—a local regime-supported group that had reportedly engaged in kidnapping and illicit dealings, including drug trafficking. This occurred in a larger context of instability, insecurity, and the proliferation of armed groups amid the breakdown of state authority in Suwayda.

The collapse of Quwwat al-Fajr was significant from a local perspective. But in the larger scheme of things, it was part of a process in which competing powers, Syrian and foreign, are trying to reshape the situation not only in Suwayda but in all of southern Syria.

As of July 23, the Damascus-Suwayda road was closed for few days at two points, in the villages of Atil and Shahba. Raji Falhout, the leader of Quwwat al-Fajr, had kidnapped members of the Tawil family, which hails from Shahba, and held them in his headquarters at Atil. His men had also closed the road to Damascus in search of more members of the family and other villagers from Shahba. In response, the Tawil family also closed the Damascus road that passed through their village, and took four hostages of their own to make an exchange. This was not unusual. Kidnappings for ransom and counter-kidnappings have been common occurrences for some time in the region.

What was unusual was how it all ended.

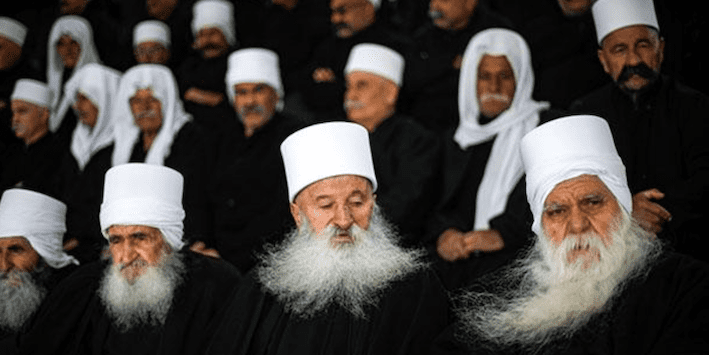

After the failure of mediation efforts to resolve the crisis peacefully, several villages, along with Shahba, mobilized to attack Falhout’s armed group. Rijal al-Karameh, or Men of Dignity, which is reportedly the best armed, largest, and most organized local armed group in Suwayda, took the lead with the blessing of Druze religious leaders. By July 26–27, Falhout was on the run, and his headquarters in Slim and Atil had been captured. Several of his men were taken prisoner, while some were later executed and their bodies disposed of in the center of Suwadya. Following this confrontation, Druze religious leaders supervised the dissolution of several other small armed groups associated with Military Intelligence.

The regime avoided an escalation. It did not protect Falhout’s militia, who was depicted by some pro-regime outlets as an outlaw who had once enjoyed regime support, but lost it after engaging in drug trafficking and kidnapping civilians and members of the military. More importantly, the regime removed the head of the local Military Intelligence branch, Brigadier General Ayman Mohammed, who had been accused of nurturing local armed groups like Falhout’s. The move was designed, presumably, to absorb local anger, yet it is unlikely to change very much.

In fact, Mohammed’s removal may well have been a continuation of an old strategy. The regime’s efforts to show leniency, even to indirectly accept blame by shuffling around local officers, was a classic move from its rulebook. The regime has also always been more considerate of the Druze community, as a minority with regional connections and a history of strong internal solidarity against external threats. This was evident in 2021, when Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajari, a senior Druze religious figure, telephoned Luay al-Ali, the head of Military Intelligence in southern Syria, asking him to release a seventeen-year-old boy from Suwadya. Ali responded by insulting the sheikh, leading to protests in the town. The regime contained the situation by sending a senior delegation to Hajari and freeing the detained boy, while proregime sources even suggested that President Bashar al-Assad had called the sheikh to emphasize that Ali’s views did reflect the regime’s. Things only returned to normal after religious leaders had released a statement asking for calm.

But the regime also has another face. It has not hesitated to bare its teeth when necessary. Just before Falhout’s fall, on June 9, a combination of regime and pro-regime forces besieged the headquarters of a local faction called the Anti-Terror Force and killed its leader. Although this could not be confirmed, the reason could have been the force’s statement of its intention to cooperate with Maghawir al-Thawra, or the Commandos of the Revolution, a U.S.-supported local faction in Tanf, where American forces are deployed. This showed that while the regime might not be able to impose its writ over the entirety of Suwayda Governorate, it still has the ability to mobilize and fight local militias when necessary.

At the broader level, even though foreign intervention in Suwayda is unprecedented both in terms of scale and number of actors, the regime remains an important player, indeed perhaps the primary one. It is hard to assess how strong Iranian influence is in the region, though it has certainly grown, especially through its ally Hezbollah. The party is accused of expanding into southern Syria, including Suwayda, and managing a drug trafficking operation that extends to the Gulf, via Jordan. In the past two years, the Jordanian authorities have struggled to secure their country’s borders with Syria in order to prevent such trafficking—especially through desert areas south of Suwayda.

Russia, in turn, often sends delegations and mediates in disputes, purportedly to expand its influence, without much success. U.S. forces, deployed in Tanf and acting through a local militia, Maghawir al-Thawra, have also started coordinating with local Druze forces. Israel and Lebanon, through their own Druze communities, have also tried to exploit their sway. These constellations of forces and their local allies often compete with the Syrian regime. Nevertheless, no one has managed to dislodge it. Suwayda is still part of the regime’s political system, and remains heavily influenced by decision making in Damascus.

One indication of this is the regime’s relations with Druze religious leaders, including Hajari. Hajari leans more toward the regime, while two other important religious figures, Yusuf Jarboua and Hammoud al-Hannawi, have adopted a more neutral position. The three are by no means united, but at no point did they move against the regime. Quite the opposite: they recognize the regime’s authority, and sometimes even yearn for the state’s return and the order it imposed. Moreover, they still regard the regime as a crucial, perhaps the most crucial, external actor in the struggle to maintain their position in Suwayda. The case of Sheikh Wahid al-Balous, the founder of Rijal al-Karameh, illustrates their attitude.

Sheikh Balous established Rijal al-Karameh in 2014. In doing so, he combined religious and secular authority at a time when the Syrian conflict had revealed the weakness of traditional leaders in most parts of Syria. In this way, the three Druze religious leaders saw it as a threat to their dominant role in society. After Balous escalated against the regime in 2015, the three, in a rare moment of unity, condemned his moves. By doing so, according to some observers, they may have paved the way for the regime to assassinate Balous in September 2015. With Balous gone, his group gradually drew closer to the religious leaders and toned down its anti-regime orientation. As for Damascus, it continues to endorse the religious authorities among the Druze, with no viable competitors for their standing.

On a broader level, Suwadya is still intertwined with Damascus. In recent years, the local economy has benefited from foreign remittances, foreign support for local armed groups, and an economy built around humanitarian assistance that offers resources independently of the regime. However, a sizable Druze community still lives in Damascus, while the city’s wholesale market remains an important gateway for Suwayda’s agricultural products. The state still provides public-sector employment—an important part of the local economy in Suwadya—and accreditation for school and university degrees, among others. Even with regard to the illicit economy, many local groups are strongly connected with the regional networks that make drugs and weapons trafficking possible, providing lucrative returns for the local population.

Suwayda has seen the growing influence of external actors and a noticeable retreat in the regime’s ability to provide economic and political rent, security, employment, and protection from external threats. Though it is weaker, the regime should not be underestimated. Suwayda continues to lie within Damascus’ political orbit. But the regime’s shortcomings have almost guaranteed that for the time being Suwayda, and indeed southern Syria in general, will remain a hotspot for instability, illicit activities, and foreign power competition.