Public opinion polling in the Arab world suggests that autocratic leaders like Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his UAE counterpart, Mohammed bin Zayed, have gotten some things right.

Both men have to varying degrees replaced religion with nationalism as the ideology legitimizing their rule and sought to ensure that countries in the region broadly adhere to their worldview.

It is a worldview that rejects any political expression of Islam, propagates a religious duty to obey the ruler with no exception, represses freedom of expression and dissent, and leaves unchallenged religious concepts such as notions of infidels and slavery that are viewed by Muslim reformers as well as significant segments of Arab youth as obsolete or outdated.

The two crown princes’ similar worldviews constitute in part a response to changing youth attitudes towards religiosity evident in various public opinion polls and also expressed in mass anti-government protests in countries like Lebanon and Iraq.

The changes involve greater importance to adherence to individual morals and values and less focus on formalistic observance of religious practice as well as a rejection of sectarianism that is a fixture of governance in Lebanon and Iraq as well as past Saudi religious ultra-conservatism.

The problem for rulers like the Saudi and UAE crown princes is that the loosening of social restrictions in Saudi Arabia, including the emasculation of the kingdom’s religious police, the lifting of a ban on women’s driving, less strict implementation of gender segregation, the introduction of western-style entertainment and greater professional opportunities for women, and a degree of genuine religious pluralism in the UAE, are only first steps in responding to youth aspirations.

Subjugation of religious establishments that turns clerics and scholars into regime parrots fuels youth scepticism towards religious institutions and leaders. It is also void of a credible theological effort to recontextualize Muslim concepts that no longer apply in a modern and changing world.

“Youth have…witnessed how religious figures, who still remain influential in many Arab societies, can sometimes give in to change even if they have resisted it initially. This not only feeds into Arab youth’s scepticism towards religious institutions but also further highlights the inconsistency of the religious discourse and its inability to provide timely explanation or justifications to the changing reality of today,” said Gulf scholar Eman Alhussein in a commentary on the latest Arab Youth Survey.

The survey found that, despite 40 percent of those polled defining religion as the most important constituent element of their identity, 66 percent saw a need for religious institutions to be reformed.

“The way some Arab countries consume religion in the political discourse, which is further amplified on social media, is no longer deceptive to the youth who can now see through it,” Ms. Alhussein said.

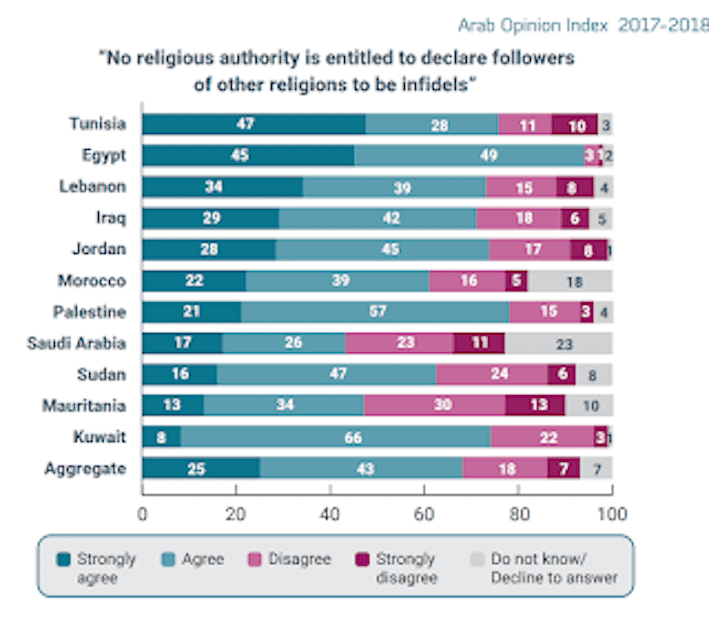

A 2018 Arab Opinion Index poll suggested that public opinion may support the reconceptualization of Muslim jurisprudence. Sixty-eight percent of those polled agreed that “no religious authority is entitled to declare followers of other religions to be infidels.”

Similarly, 70 percent of those surveyed rejected the notion that democracy was incompatible with Islam while 76 percent viewed it as the most appropriate system of governance.

What that means in practice is, however, less clear.

Arab public opinion appears split down the middle when it comes to issues like separation of religion and politics or the right to protest.

Michael Robbins, director of the Arab Barometer, another pollster, cautioned in a commentary in The Washington Post, co-authored with international affairs scholar Lawrence Rubin, that recent moves by the government of Sudan to separate religion and state may not enjoy public support.

The transitional government brought to office last year by a popular revolt that topped decades of Islamist rule by ousted President Omar al-Bashir last month agreed in peace talks with Sudanese rebel groups to a “separation of religion and state.”

The government also ended the ban on apostasy and consumption of alcohol by non-Muslims and prohibited corporal punishment, including public flogging.

Messrs. Robbins and Rubin noted that 61 percent of those surveyed on the eve of the revolt believed that Sudanese law should be based on the Sharia or Islamic law defined by two thirds of the respondents as ensuring the provision of basic services and lack of corruption.

The researchers, nonetheless, also concluded that youth favoured a reduced role of religious leaders in political life. They said youth had soured on the idea of religion-based governance because of widespread corruption during the region of Mr. Al-Bashir who professed his adherence to religious principles.

“If the transitional government can deliver on providing basic services to the country’s citizens and tackling corruption, the formal shift away from Sharia is likely to be acceptable in the eyes of the public. However, if these problems remain, a new set of religious leaders may be able to galvanize a movement aimed at reinstituting Sharia as a means to achieve these objectives,” Messrs Robbins and Rubin warned.

It is a warning that is as valid for Sudan as it is for much of the Arab and Muslim world.

Asked in a recent poll conducted by The Washington Institute of Near East Policy whether “it’s a good thing we aren’t having big street demonstrations here now the way they do in some other countries” – a reference to the past decade of popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Algeria, Lebanon, Iraq and Sudan, Saudi public opinion was split down the middle. 48 percent of respondents agreed, and 48 percent disagreed.

Saudis, like most Gulf Arabs, are likely less inclined to take grievances to the streets.

Nonetheless, the poll indicates that they may prove to be more empathetic to protests should they occur.

Taken together, the various polls suggest that at a time of economic downturn and inevitable transition that puts a premium on delivery of public goods and services as well as good governance, Arab and Muslim leaders could find changing attitudes towards religiosity to be a double-edged sword.

Performance could turn it into an asset but that would have to involve greater independent bottom-up civil society engagement for which there is more often than not little scope. A failure to deliver could turn it into a threat.

A podcast version of this story is available on Soundcloud, Itunes, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, Spreaker, Pocket Casts, Tumblr, Podbean, Audecibel, Patreon and Castbox.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. He is also a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute and co-director of the University of Wuerzburg’s Institute of Fan Culture in Germany