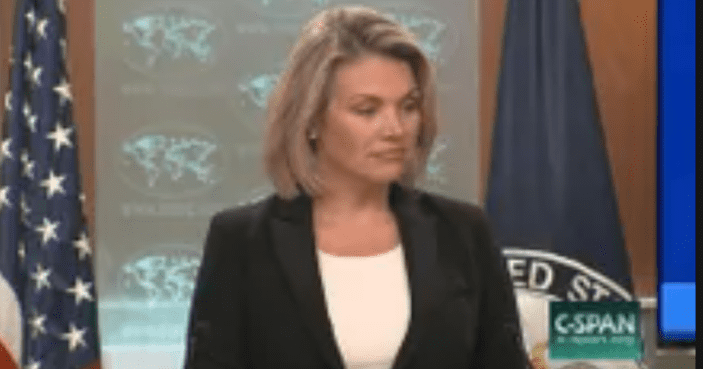

MS ORTAGUS: Thank you very much. Good morning, everyone. Thank you for joining us early on this on-the-record briefing, which is embargoed, please, until the end of the call. This is an update on PRC efforts to push disinformation and propaganda around COVID-19. The Secretary has said repeatedly that transparency, accountability, and information sharing are the best tools for stemming the tide of COVID-19’s global impact. And yet we have identified a new network of inauthentic accounts on Twitter most likely designed to amplify PRC propaganda and disinformation related to the pandemic. These inauthentic accounts ranging in the thousands are being used to positively paint China’s response to COVID-19 and to criticize anti-PRC content. Lea Gabrielle, our special envoy and coordinator of the Global Engagement Center, has joined this call to provide more details on these findings. After her opening remarks, we’ll be available for your questions. Just a reminder that the contents of this briefing are embargoed until the end of the call.

Additionally, as our AT&T host said, please dial 1 and 0 if you would like to ask a question. We are on a time constraint today. Lea has to end right at 10 a.m., so we will attempt to get to as many questions as possible, so please keep them brief so your colleagues can also ask a question. Okay, Lea, over to you.

MS GABRIELLE: All right, good morning. This is Special Envoy Lea Gabrielle. As Morgan mentioned, I lead the Global Engagement Center, and it’s really good to be back with everyone today. Since I last spoke with you, we’ve seen other look closely at the convergence of Russian and Chinese disinformation narratives, and to give you an update, we do continue to see Chinese and Russian narratives converge and echo each other. Most recently we saw CCP and Russian proxies recirculate false narratives about U.S.-funded biolabs in the former Soviet Union, as just one example. So even before the COVID-19 crisis, we assessed a certain level of coordination between Russia and the PRC in the realm of propaganda, but with this pandemic the cooperation has accelerated rapidly. We see this convergence as a result of what we consider to be pragmatism between the two actors who want to shape public understanding of the COVID pandemic for their own purposes. So this disturbing convergence of narratives is just an example of how Beijing is adapting in real time and increasingly using techniques that have long been employed by Moscow.

And today I just want to dig in on Beijing’s use of bot networks to push its narratives on social media platforms, those social media platforms that open and free societies use to communicate and to learn what’s happening in the world but that are blocked in China. So just to frame it, according to the nonpartisan think tank the German Marshall Fund, Twitter accounts linked to the Chinese embassies, consulates, and ambassadors have increased by more than 250 percent since the start of the Hong Kong anti-government protests in March of 2019. Now from September to December alone in 2019, China’s diplomatic corps created more than 40 new accounts, and that’s about the total it had for April of 2019. Now at the same time, we’re seeing an increased use of bot networks to amplify Chinese narratives. Twitter, for example, itself identified a network of 200,000 accounts in August following an investigation that found reliable evidence support that that was a coordinated, state-backed operation attempting to sow political discord in Hong Kong.

Now throughout the COVID pandemic, several organizations have reported on bot networks promoting pro-CCP narratives. And what I’d really like to highlight is that the GEC has uncovered a new network of inauthentic Twitter accounts which we assess were created with the intent to amplify Chinese propaganda and disinformation. In this case our analytics team looked at the most recent followers for 36 Twitter accounts of either Chinese foreign ministry officials or the official accounts for Chinese embassies. Many Chinese diplomatic Twitter accounts experienced a major surge in the number of new followers since March, and that matches the timeframe in which Beijing’s overseas messaging effort kicked into high gear around COVID.

So to be more specific, starting in March of 2020, the number of recently created new followers per day for these accounts went from a historical average of about 30 per day to over 720 per day. That’s a 22-fold increase, and many of these new followers were newly created accounts. So both the sudden increase of followers and the very recent creation of many of these accounts points to an artificial network being established to follow and to amplify narratives from Chinese diplomats and foreign ministry officials, especially at a time when China’s adopting Russian-style disinformation techniques to sow confusion and to try to convince people that COVID didn’t originate in China. And this trend escalated from March into May.

Now based on the characteristics, content, and behavior of these accounts, the GEC assesses linkages to the Chinese Communist Party are highly probable. We also assess that this is a coordinated and interconnected effort. Nearly every diplomatic account shares at least one follower with every other account, with some instances of diplomatic accounts sharing more than a thousand followers.

So to give an example, two accounts that are linked to the Chinese foreign ministry, @zlj517, which is MFA Deputy Director Zhao’s account, and @spokespersonchn, which is the MFA spokesperson account – these two share 3,423 of their most recent 10,000 followers, and nearly 40 percent of the most recent followers were created in just a six-week period between the 1st of March and the 15th of April, 2020. So it’s our assessment that this network could be deployed to allow the CCP to rapidly amplify and spread messages around the world, skewing the conversation to its benefit. This sort of coordinated activity also threatens to overshadow the organic conversations taking place on these platforms the way these platforms were intended, to have organic conversations.

So from promoting conspiracy websites to the use of trolls and bot networks to pushing false narratives couched in science on Chinese state media, Beijing has engaged in an aggressive information campaign to try and reshape the global narrative around COVID. It’s doing this in attempt to make the world see China as the global leader in the response rather than the source of the pandemic.

But we will say that the efforts are backfiring in many places. We’ve seen foreign governments, academics, and media call out CCP disinformation and propaganda and join the U.S. in our demand for transparency. Concerns about how the CCP tries to manipulate information are global ones, and it’s critical that we continue to draw attention to the CCP’s increasing use of disinformation and other Russian-style tactics, like these inauthentic social media amplification networks, to prevent these behaviors from becoming the norm for Beijing.

So that is my update for today, and I’m happy to take your questions.

MS ORTAGUS: Thanks, Lea. We’ve got a number of people in the queue already, and let me just remind people, if we don’t get to your questions since we have so many, we will – you can submit questions to me and Cale in writing, and we will be happy to try to get them answered.

So let’s – the first person in the queue is Jennifer Hansler, CNN.

QUESTION: Hi, thanks so much for doing this. I was wondering if you could speak a little bit about whether you’re seeing active coordination between the Russian and Chinese on these disinformation efforts. And then separately, on some of these anti-stay-at-home protests here in the U.S., have you seen any evidence that foreign governments have been behind amplifying or fomenting these protests? Thank you.

MS GABRIELLE: Okay, thank you so much for that question. For the first part of it, are we seeing active coordination between Russia and China in these disinformation efforts, it depends on the definition of “active coordination.” What we are seeing is a convergence of narratives. We’re seeing a bouncing off of each other. I think there are some examples where we have basically seen a narrative pushed out by a state actor then repeated by another one. So we’re certainly seeing them bounce off of each other and essentially play together in the information space. How active that coordination is government to government is not something that we can currently assess.

And then to your question about the issues within the U.S., I’d have to refer you to domestic agencies, as anything that’s happening in the domestic information space would not fall under my purview.

MS ORTAGUS: Thanks. Okay, Joel Gehrke.

QUESTION: Hi, thank you for doing this. Two – two discrete ones. One, you mentioned that – in a briefing earlier this week that you expect the Russians to undermine trust in a vaccine. I wonder if you think that the Chinese networks will join that effort, and what the motives for doing that would be. And then a little more broadly, if China is now developing these sort of Russian-style disinformation tactics in this moment, do you think we’re crossing a watershed where we could be looking at the kind of election interference or other public-facing disinformation operations we’ve seen from Russia but with far more resources from the Chinese side?

MS GABRIELLE: Okay, so first, to answer your question about the potential for Russia or China undercutting vaccines, I think you kind of have to look at what we’ve seen in the past, in a short period of time, looking within the CCP information environment. What we saw during the COVID crisis is the CCP going from allowing Russian disinformation that was claiming the U.S. was the source of the virus to spread around in Chinese social media, to then the CCP basically raising questions themselves on state media about the origin source, and then promoting disinformation that the U.S. is the source of the virus. And at the same time, we saw Beijing unleashing a drumbeat of pro-PRC content across its global media networks and from its overseas missions that included vocal criticism, increasingly vocal criticism about democratic countries and how they’re responding to crisis.

So I think if you look at that as an example of how you see the CCP and Russia interact, it’s likely that anything that would support the CCP’s overarching initiative of reshaping the global narrative to make Beijing look as though it is the leader in the global recovery and not the source of the problem, I think anything that supports that you can expect it to be parroted essentially. But again, it’s always hard to predict the future. I don’t have a crystal ball.

You asked about where we are in terms of China using Russian-style disinformation techniques, is this a watershed moment. And you mentioned going into the elections. I think one of the things that we have to consider right now is what’s essentially a one-way megaphone from the CCP into free, open, democratic societies. So the CCP’s decade-long effort to control information within China is well documented. But unfortunately, general populations just aren’t aware enough of this. And so now the CCP’s censorship, its silencing of voices within and into China, is being matched by aggressive CCP efforts to push propaganda and disinformation across a massive global information ecosystem, including the major social media platforms that are used by free societies but that are blocked within China.

So this results in what I just described as essentially a one-way megaphone from the CCP to the free world. And for the CCP, these platforms are stages where they can blast from their one-way megaphone. So general populations may just not realize that every single time they see CCP narratives from CCP officials on these open social media platforms, it is a one-way megaphone while they’re locking their own general populations off from being able to see what free societies have to say. And that’s the real concern here, is that ability to use that platform to transmit into open, free societies’ social media environment with no return.

MR BROWN: Okay, lots of people in the queue, so let’s try to keep our questions per person down. Next let’s go to the line of Nick Wadhams.

QUESTION: Thanks very much. I just wanted to follow up on Jennifer’s question. Setting aside the issue of the protests, do you see China mimicking the Russian campaign of recent years of trying to sow discord and dissent within the United States from these accounts? Thanks.

MS GABRIELLE: I’d have to have my analysts look into that question more deeply to give you an answer, but what I can say is that we’re seeing the CCP adopt Russian-style tactics. And what it appears is that what they assess to be working is what they’re starting to use as well. So I can certainly have our analysts look more into that question, and we’ll be assessing it as we move forward, but I don’t want to give you an answer that I can’t be certain of right now.

MR BROWN: Okay. Let’s go to Bill Gertz.

QUESTION: In 2017, the acting general counsel for Twitter, Sean Edgett, said that to the extent we are able to identify any foreign links associated with an account and determine that it’s functioning as state-sponsored propaganda, Twitter reserves the right to take action on the account. Have you approached Twitter on this, and why haven’t they shut down these official state-sponsored propagandas?

MS GABRIELLE: Okay. So I can’t speak for the social media platforms, but I can tell you that we have shared with Twitter on this. But what I want to really focus on is that the picture is different for the GEC in terms of what we’re trying to do. With the GEC’s mission being to counter foreign propaganda and disinformation, it’s different than what any one platform may be seeing. We’re looking at the entire disinformation ecosystem, and the disinformation ecosystem problem is much bigger than any one social media platform. The issue really is how the information environment writ large is being intentionally artificially manipulated. And what I’ve given you today is really just the latest example.

And I’m not hearing any questions right now, so perhaps our host is muted.

MR BROWN: Operator, can you open the line of Rita Cheng?

QUESTION: I’m on the line. Thank you for doing this. I’m just wondering now: Have you seen any evidence that disinformation can maybe operate by the PLA, or is it still like a civil-military mix operation? Thank you.

MS GABRIELLE: So we have been assessing a lot of this using unclassified data sets and working with partners worldwide, and we do that because we want to be able to share as much with our partners as possible and as much publicly as we possibly can. So you’re asking about specifically PLA, but I think the same question could be asked towards how – what’s the level of control from the PRC.

And so what I’d say is: Much like we assess that something is Russia-backed, we look at what the narratives are promoting, who they’re networking with, how coordinated the activity is, if it’s being manipulated in strategic times – like it’s happening here during COVID-19. We look at if bots are involved. We look at if these accounts are being created during and doing most of their activity during Beijing business hours. And these accounts that I just talked about today, most of them were created during those hours. All of this really leads to our assessment that they are likely – that it’s highly probable that they’re linked to the PRC, but I couldn’t go into more details about potential PLA linkages at this time.

MR BROWN: Okay. Next, Ed Wong.

QUESTION: Thanks. Can you tell us a little bit more about technically how these bot accounts work? How many do you assess have actual people sort of running them, and how many others are pushing out information through some other technical process? And also, what are the – what exactly do the majority of the accounts do or – through their tweeting, like do they just retweet things from the diplomatic accounts or are the majority of their tweets something else?

MS GABRIELLE: Okay. So first of all, we’re seeing a lot of retweet activity from these. They appear as though they are intended to amplify accounts. You’re asking how many are actual people compared to other technical ways of using accounts, and I could try to get some more details for you on that, but what I’ll tell you is that the shape of the follower network reveals what we assess to be a mechanism for rapidly amplifying pro-PRC messages.

And again, as I said before, nearly every diplomatic account that we analyzed shares at least one follower with every other diplomatic account, and we’re observing, for example, a follower account following the PRC embassy in Manila but also the one in Ottawa, or the PRC embassy in Sri Lanka and also the PRC embassy in Samoa. So it’s the amount of these accounts that are following multiple geographically separated PRC embassies and the PRC foreign ministry officials that make them suspicious. So it’s not typical behavior. And on top of that, I mentioned before that these same accounts are newly created, so taken together, this points to highly unlikely that it would be organic activity.

So I mentioned the shape of the follower network. We also looked at the amplifier accounts themselves, looked at what are some of the most active accounts that are amplifying PRC officials to do our assessment, and oftentimes what they’re doing is amplifying those accounts, as I mentioned, but we could certainly look into more details for you.

MR BROWN: Amanda Seitz, AP.

QUESTION: I was wondering if you’re – thank you for hosting this. And I was wondering if you are seeing any of the inauthentic bot-like behavior on other social media platforms outside of Twitter. And when you talk about amplifying the similar messages from Russia, if you could expand on any of those narratives that you’re seeing, what exactly they are.

MS GABRIELLE: Okay. So you’re asking if we’re seeing this inauthentic bot-like behavior on other social media accounts outside of Twitter, and the answer is yes. As I mentioned, this particular assessment and analysis that we did was focused on what we saw in terms of this new network of inauthentic Twitter accounts that were created, as we assess, to amplify Chinese propaganda and disinformation. But we do look at the entire disinformation ecosystem, so that ecosystem ranges from state-sponsored accounts, state platforms, proxy websites that push out conspiracy theories that are then bounced off by other accounts. So it’s an entire picture.

And what we’re really looking at is what I said before of how we’re seeing CCP officials use the social media environment in open, free, democratic societies as a one-way megaphone into those populations to influence while cutting off their populations from hearing what – that – what discourse is happening from our populations. And so I think that’s what I really want to highlight there.

And then specific narratives. The narratives that we’ve seen converge again and again are on the origins of the virus, that – trying to push the narratives that they did not – that the virus didn’t originate in China, trying to point the finger somewhere else. From Russian accounts, sometimes it’s just trying to create confusion.

MR BROWN: Laura Kelly, The Hill.

QUESTION: Hi, can you hear me?

MR BROWN: Yes. Go ahead.

QUESTION: Hello? Okay. Thank you. Thank you for doing this. I’m wondering if you can talk about who, what regions, or what population the Chinese are trying to target with their information and with their narratives, or are you just kind of seeing it all over?

MS GABRIELLE: We’re seeing it worldwide. We’ve seen heavy – we’ve seen a heaviness of this effort in the EUR region. I’m actually flipping through my report right now to look at some of the data because I do remember seeing that there was a heavy focus in the EUR region on this. But this is really global. We’re seeing separate amplification mechanisms in place for the regional diplomatic accounts that I mentioned before. So yes, I am seeing right here that the accounts located in EUR did have the most shared followers; 12,688 shared accounts is what I just saw. But again, it’s follower accounts, following PRC embassy in Manila but also Ottawa, and some of those other examples that I mentioned of how it’s really a global effort.

MR BROWN: Humeyra Pamuk. Humeyra, go ahead.

QUESTION: (No response.)

MR BROWN: Okay. Not hearing anything from her, let’s go to David Sanger.

QUESTION: Thanks very much for this. If I return to the question – the first question that you had which dealt with the issue of potential collaboration between Russia and China. So as you’ve described this, it could just be mimicking behavior, which happens all the time and not just with Russia and China. The Chinese may – would mimic others who had successful strategies.

But you said right now you didn’t have any evidence of government-to-government coordination. Does that mean that you haven’t found any? Does that mean that there are – there is no effort underway in the Intelligence Community right now, including the State Department, to figure that out? It strikes me that’s the single most important element of your argument here if, in fact, there was collaboration.

MS GABRIELLE: Well, first of all, I’d say the single most important element here is identifying what’s actually happening in the information space and how inauthentic activity is being used to change the shape of the discourse that’s happening in open and free societies.

In terms of government-to-government coordination – you mentioned the Intelligence Community. I certainly would not speak to any sort of classified information on this call or in this space. That would take a process for anything that’s happening in the classified space to be declassified to be able to be shared. So I’m very much focusing on what we can share from the unclassified perspective.

I think you can look back and look at even before the COVID-19 crisis, we saw some level of coordination between the PRC and Russia. For example, Russia’s state-controlled news agency Sputnik has agreements with Chinese media outlets where they exchange content, they exchange personnel, and it’s hard to measure how much is actually substantive there, but it’s noteworthy that they have taken those steps. They also have held annual media exchange forums for the past five years and those have leading media agencies from each country and government officials, and in those media exchange forums they’ve called for bolstered cooperation on both traditional and new media.

So I think it’s important to point out that that collaboration is there on some level. I don’t want to overemphasize it, though. We, again, as I said, are trying to share what we can see in the unclassified space where we can work with our partners and allies and share this information, because I think that’s really important.

I also just want to give an example. I was asked by the Associated Press about some of the narratives and how we’re seeing Russia amplify others, and I thought of an example that I should probably mention that’s a little more specific. So we saw that in Italy, we saw Russian-linked social media accounts were amplifying content that was promoting pro-Chinese narratives. So, tweets, for example, from China’s MFA and the Global Times to Italian audiences. So we saw a pro-China narrative that was related to China’s aid to Italy, and the GEC in that case analyzed tweets that were coming from 18 Russian-linked Twitter accounts within Italy’s Twitter conversations in the month of March. And the total volume of posts from those accounts was 65,600 with about 25 percent related to COVID-19.

And one tweet was amplified by China’s MFA spokesperson shared a video that claimed that the Chinese national anthem was played in the streets as China’s doctors arrived in Italy, and that was later debunked by a fact-checking organization, and in fact, an Italian fact-checking organization as fake. So that video appeared to show Italians saying, “Thank you, China,” when actually these Italians citizens were thanking their own health care workers, not the Chinese doctors. But PRC diplomats and party state media changed the context of the video in Beijing’s favor and then shared it widely. So that’s an example of where we saw Russian-linked accounts amplifying Chinese narratives, and that’s a more specific example for you.

MR BROWN: Okay. We have time for one more.

MS GABRIELLE: I’m sorry, Cale. I actually do have a hard stop at 10:00 and I think it’s 10:01, but I just want to say I really appreciate the great reporting from everyone on this and the interest, and I look forward to speaking with all of you again soon. Thank you.

MR BROWN: Thanks, Lea. Thanks to everyone for joining the call, and since we’re at the end, the embargo on the contents is lifted. Have a great day.