When Iraq’s finance minister stepped down last month, he didn’t go quietly.

On August 16, as the leading members of Iraq’s government gathered for their weekly cabinet meeting in a high-ceilinged hall of the Republican Palace in Baghdad, one of them made an unusual request. Ali Allawi, the finance minister since 2020, was stepping down, and he wanted to read the full text of his resignation letter aloud. Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi gave his assent.

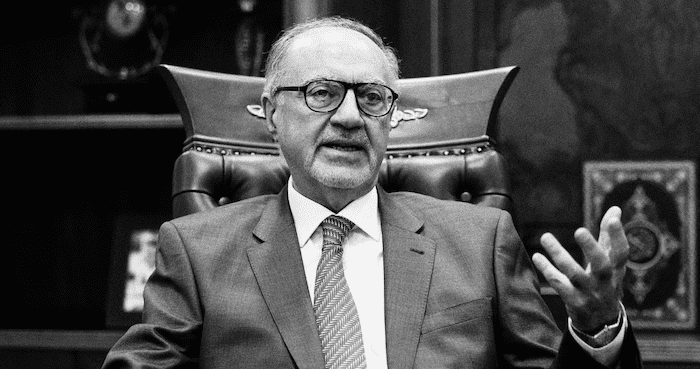

Allawi, a 73-year-old former banker and Oxford don with an air of owlish gravitas, started off with the usual bureaucratic niceties: a gracious thank-you to the prime minister, an assurance that the country’s finances were in relatively decent shape. But he went on to deliver a comprehensive indictment of Iraq’s political class that may be among the most stinging resignation letters ever written. When future historians write about Iraq’s troubled effort to build an American-style democracy in the early years of the 21st century, Allawi’s letter will provide them with a rare insider’s view of a failing state.

The letter detailed a series of outrageous scams that had been approved or promoted by some of the men around him, who, he said, had helped create a “vast octopus of corruption and deceit” that was poisoning the entire country. The letter built gradually toward a conclusion that was almost apocalyptic in scale. Iraq, Allawi said, was on the point of collapse, facing “a crisis of state, society, and even the individual.” The problem was not just dishonest leaders, but the entire system put in place by the Americans two decades earlier. “I believe,” he said, “we are facing one of the most serious challenges that any country has faced in the past century.”

It took a full half hour to read the letter, and Allawi was met with stunned silence. No one had expected a self-effacing elder statesman like Allawi—the author of several critically acclaimed books—to produce such a blunt jeremiad. Although it made news in Iraq, the episode went almost unnoticed elsewhere and was eclipsed later in August by the outbreak of violence: Two Shiite factions squared off in Baghdad, leaving dozens dead. The country has been rudderless since the last round of elections a year ago, with negotiations to form a new government going nowhere.

In Western capitals, Allawi’s resignation was greeted with dismay. Before he returned to Iraq in mid-2020, Allawi had been one of the loudest voices warning about corruption in the country, and he was widely seen as an avatar of financial integrity and competence. I spoke with him at length while reporting an article on Iraqi corruption that was published later that year. His grasp of the subject, and his anger about it, impressed me.

After serving as a minister in Iraq from 2003 to 2006, Allawi came back almost by accident. The massive street demonstrations that broke out in late 2019 led to the collapse of the government, and after months of failed negotiations, the country’s political factions agreed on a compromise candidate for prime minister who threatened no one because he had no political party and no militia. Al-Kadhimi was the head of Iraq’s main intelligence agency, a thoughtful administrator who had started off as a human-rights activist. He promptly appointed Allawi and several other technocrats. To some outside observers, it looked like a dream team, and perhaps Iraq’s last chance for renewal.

Allawi made himself a chart showing which ministry employees answered to which political party. The real powers were the party bosses, the oligarchs, and the militia leaders. They treated even the government’s nominal leaders like lackeys. Allawi wrote that at one point, he was threatened with a travel ban after he refused a summons from a party boss. Allawi and al-Kadhimi had been hailed as Iraq’s potential saviors, because they were free of the taint of Iraqi politics. But that left them with very little leverage in a country where power is exercised through armed street gangs, stolen money, and religion.

Allawi worked to expose old fraudulent contracts and block efforts to implement new ones. One of these schemes was based on an electronic-payment system called Qi Card that was intended to help government employees and pensioners retrieve their salaries more easily. The system was run with no oversight, and it became a tool for Iraqi oligarchs and militia leaders to skim salaries and drain money through “ghost soldier” schemes. I wrote about Qi Card in 2020, and the company’s chief executive was arrested not long afterward. It seemed an important victory for reform at the time.

But one of Iraq’s most notorious oligarchs proposed a new electronic-payment system to replace Qi Card. This one was even worse. On top of the likelihood of continued graft schemes, the new company imposed a clause awarding itself a $600 million penalty if the government contract was abrogated. Amazingly, that contract was approved by the board of Iraq’s main state-owned bank, despite Allawi’s efforts to block it. It is still being litigated.

That contract, Allawi wrote, “was for me the straw that broke the camel’s back. It crystallized the degree to which the state had become degraded and become a plaything of special interests.”

Allawi spent much of his first year in office writing a plan for reform. But in his resignation letter, he suggested that all such efforts are doomed, not just by corrupt politicians, but by “the political framework of this country.” The system put in place during the American occupation, intended to foster political competition and power-sharing, has instead become a consensual process in which Iraq’s oil money, funneled through the ministries, is divided up by oligarchs and the militias that protect them. This system is virtually the only game in town, because an unusually large percentage of the population works for the government, and efforts to build a viable private sector have been deliberately stifled. All of this means that Iraq is more dependent than ever on oil revenues. If those collapse, the entire country will go bankrupt—excluding the oligarchs with gracious homes in London.

When I spoke with Allawi last week, he sounded melancholy but not regretful. He said that he had thought at length about the decision to step down. He worried that he was becoming a kind of fig leaf, providing reassurance to Iraq’s foreign supporters but unable to do anything about the rot. Ultimately, he told me, “it was a moral stand. I wanted to wake people up. That what they think of as significant acts of corruption are nothing compared with what’s under their noses. Their future is being sold.”

The reaction to his letter in Baghdad was mixed. Some columnists praised him for his frankness and castigated the country’s elite for not listening. But among the lawyers and social activists I spoke with, some seemed to feel that Allawi’s gesture was self-serving, that he was protecting his legacy or justifying his unwillingness to keep fighting. There may be some truth in all these perspectives. I also suspect that Allawi was simply exhausted.

The most unexpected reaction came in a text message that Allawi received (in Arabic) several weeks after he resigned. It was written by what Iraqis call a whale—the local word for the corrupt oligarchs who seem to hold the country’s fate in their hands.

“I hesitated a lot before writing this letter,” the businessman begins, adding that he went ahead because he was impressed with Allawi’s sincerity and patriotism. He says he agrees with much of what Allawi said in his resignation letter, but not the part where Allawi mentioned the businessman’s own company and its role at the center of a notorious corruption scandal. He says he hopes to gain Allawi’s friendship and seek his advice. “I hope one day we can sit in one of the suburbs of London, and I can tell you my side of the story, so that your judgment is fair.”

Allawi did not write back.