While the negotiations on the maritime border are progressing, the UN reports increasing aggression from the Iran-backed organization, which managed to upgrade the air defense systems in Lebanon

A surprising feeling of optimism has emerged in recent days in the three-way negotiations among Israel, Lebanon and the United States to determine the maritime borderline between Israel and Lebanon. After weeks of anxiety, and even a mild threat of war, it seems the parties are getting close to an agreement.

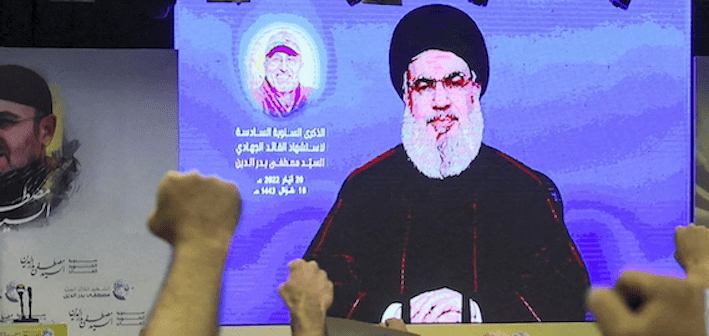

That is what Israeli officials were saying at the start of the week, and similar sentiments were heard by Amos Hochstein, the U.S. mediator, who came to Israel after discussions with officials in Beirut. Will Hassan Nasrallah, the head of Hezbollah, who earned tons of free media coverage with his threats to attack the drilling platform for Israel’s Karish offshore natural-gas field, be satisfied with the understanding that has been reached? Will he take credit for any agreement and declare quiet for the rest of the summer? Stay tuned.

However, even if the problem of the maritime border is solved and drilling at Karish can get underway in the next month without needless disruptions, it is difficult to ignore the impression that there has been a fundamental change for the worse along the two countries’ land border and in the skies over Lebanon. Some of these things are evident on the ground. Others are manifested in official statements to the media and in the latest report submitted by the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon to UN headquarters in New York.

The common denominator on land, sea and air is a more militant and aggressive stance by Hezbollah and a greater willingness than in the past to risk confrontation with Israel. In response, it appears that Israel is being careful not to allow this to escalate. But even this change has implications. A reduction in freedom of action by the Israel Air Force in Lebanese airspace may reduce the extent of intelligence-gathering on Hezbollah activities and undermine Israeli confidence in the reliability of the information it does have. Good intelligence actually acts as a restraining factor against escalation.

In February, Nasrallah claimed that thanks to Hezbollah’s air defenses Israel has had to restrain its operations. In Bekaa, the valley in eastern Lebanon, as well as in south Lebanon, he said, Israeli drones haven’t been seen in the skies for months. He even made a more expansive claim to the effect that the Israel Defense Forces can no longer do anything to stop Hezbollah’s manufacture of precision-guided missiles in Lebanese territory. Amikam Norkin, who served as the commander of the IAF from 2017 until early April, admitted in an exit interview with Israel’s Kan public television that Israeli freedom of action had in fact been reduced. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. (res.) Assaf Orion wrote last month in an article on the website of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy that “operational conditions in the country’s skies have changed to the IDF’s disadvantage, hampering some of its intelligence efforts while heightening the potential for wider conflict with Hezbollah.”

Orion noted that over the past decade Israel, as part of its so-called war between the wars, had targeted many of its attacks in Syria on the batteries and anti-aircraft missiles Iran sought to smuggle to Hezbollah. However, in recent years the Shiite organization has succeeded to significantly upgrade the air defenses it has deployed across Lebanon. In 2019, Nasrallah threatened to attack Israeli drones flying in Lebanese airspace following a drone attack on Dahiyeh, a Shi’ite Muslim neighborhood in south Beirut. Since then, Hezbollah made several unsuccessful attempts to shoot down Israeli drones. Security sources recall an incident in which the IDF recommended a retaliatory attack in Lebanon but that the prime minister at the time, Benjamin Netanyahu, ultimately decided against it.

Orion, whose last assignment in the IDF before his retirement from the military was head of strategic planning, liaison and international cooperation in the General Staff’s Planning Directorate – including liaison with the UN – examined the reports the United Nations’ secretary-general presents to the Security Council three times a year in which it documents violations of sovereignty and other limits set out in UN Security Council Resolution 1701, which defined the rules of the game in the wake of 2006’s Second Lebanon War. In the past year and a half, the reports have documented a “dramatic decline” in Israeli activity in Lebanese skies (the overflights are, of course, violations of Lebanese sovereignty). According to the reports, Israeli activity has dropped between 70 and 90 percent in the past year in comparison with previous years.

Orion explains that paradoxically a reduction in Israeli overflights may increase the likelihood of a flare-up. After Hezbollah’s surprising demonstration of strength during its last war with Israel, Israel stepped up efforts to collect intelligence on the organization’s military activities But intelligence needs to be constantly updated, which means the collection of information must be continuous. Hezbollah’s ability to erode Israeli air superiority in Lebanon will require Israel to seek alternatives to its current means of intelligence-gathering. Even then, Orion writes, Israel will face a dilemma: To accept a gradual decline in the quality of intelligence it has or to continue the aerial-photography missions at the risk of encountering Hezbollah’s air defense systems.

In Syria, Israel has systematically attacked Iranian anti-missile systems, including ones deployed by the Revolutionary Guard to help protect the Assad regime’s military assets. In Lebanon, Israel rarely acts, and the decision to attack the batteries there could have far-reaching consequences. Orion concludes: The two sides have for a long time been walking a tightrope between deterrence and escalation, but now that Hezbollah has stepped up its activities against what Israel regards as its main military and intelligence tool, the risks have become greater.

Israel’s ‘war between the wars’

Orion’s article raises another question that he only relates to on the margins: What does the new strategic reality teach us about Israel’s war between the wars? In the last several years, it has become the be-all and end-all, at least in the IDF’s eyes. Things reached a point over the past few months that the imperative of continuing operations in Syria and avoiding friction with the Russian forces there served as an excuse for Israel to refrain from taking a moral position vis-a-vis Russian war crimes since it invaded Ukraine.

But if Israel has only enjoyed partial success in preventing Hezbollah’s “precision project” – not only because hundreds of precision-guided missiles have reached Lebanon but because Nasrallah now says that his organization has the ability to produce them locally, it appears that Israel has had trouble thwarting the smuggling of air defense batteries. This raises other questions: Are all the achievements that Israel has made in the war between the wars due to the attacks themselves or are they partially due to Iranian or Russian calculations? Does the constant preoccupation with the war between the wars – scores of attacks every year, hundreds of hours of deliberations during operations by senior officials in the underground national military command center in Tel Aviv’s Kirya, known as the “Bor,” Hebrew for “pit” – come at the expense of preparations for an actual war?

Another issue relates to Hezbollah’s violations on the ground. At the end of June, Haaretz reported that Hezbollah had erected within two months no less than 16 observation points along the border with Israel using the environmental group Green Without Borders as a cover. Hezbollah creates facts on the ground, provokes Israel and collects tactical intelligence without UNIFIL able to fulfill its mission of preventing the organization from operating south of the Litani River.

The UN reports point to a broader trend reflected in this activity. UNIFIL personnel have documented a significant increase in Hezbollah violations and more hostility toward its patrols. In the relatively rare helicopter flights it has made over south Lebanon, the United Nations has seen Hezbollah increasingly engaging in small-arms training. It has conducted exercises across the entire sector over a relatively long period of time, and in one case 25 militants participated in them. In addition, there has been a marked rise in violent attacks and harassment of UNIFIL troops in the form of roadblocks, beatings, stone-throwing and threats.

As Orion sees it, despite the hopes of reaching a satisfactory conclusion to the dispute over Mediterranean gas rights, border developments are more worrying. “Hezbollah is acting as if no one can stop them,” he told Haaretz “They are radiating excessive self-confidence and don’t think they will pay the price for it. That is dangerous hubris the likes of which I haven’t seen in years.”