Alexander Rayko Alexiev was named for his father, the famous painter, caricaturist, and satirist Rayko Alexiev, who was tortured and killed by Bulgaria’s Soviet-backed communist regime in 1944. His mother was dispatched for many years to Bulgaria’s gulag from which she was fortunate to emerge alive. These events created the context for their son’s life and work, which was intense, focused, intellectually profound, spirited, and inspirational. Unsurprisingly, Alex harbored a deep-seated hatred of communism and those who claimed to follow it, or who advanced preposterous claims on its behalf.

He was raised largely by his grandparents and other relatives, for whom he had the deepest love and respect. His grandfather, in particular, figured in many of Alex’s recollections of his childhood, which were invariably full of dark humor. The son of “anti-social” parents, Alex was denied most of what those in the communists’ favor took for granted, though he was permitted to study English literature at Sofia State University. As a military-aged young man, he was sent to serve in a Bulgarian army construction battalion, where dissidents, political undesirables, and ethnic minorities were kept away from the rest of the troops. Little did the authorities know that this experience would help inform one of Alex’s most ambitious and successful efforts several decades later to reveal the inherent fragilities of Soviet power.

Like so many others who shared this reality, Alex escaped it in 1968 by fleeing across the border of what was then Yugoslavia. It was a dangerous journey, but he wasn’t content to move on with his own safety in hand. He returned to the border several times to shepherd across dear friends and guide them to freedom. He was a man of monumental physical courage.

Alex spent time in Munich, where he was initially tossed in jail as an escapee from the East, but he took advantage of that brief sojourn to perfect his German and to study. Eventually with the help of other Bulgarian émigrés, he emigrated to the United States, not to the glitter and bright lights—at least not yet—but to Indianapolis, Indiana, in the heart of the American Midwest, where he worked as an electrician’s apprentice. He escaped that reality through frequent trips to the West to work in the lumber and fishing industries. He also fell deeply in love with the American outdoors. Hunting, fishing, skiing, hiking, and just lying about in a tent with a good bottle of something surrounded by wildlife and wilderness became lifelong obsessions.

By the mid-1970s, Alex had found the bright lights of Los Angeles, where he was destined to spend the next several decades. At that time, the political science department of the University of California at Los Angeles had a kind of internship program with the nearby Rand Corporation, the world-renowned think tank, in Santa Monica. From UCLA, Alex became part of Rand’s national security team. Rand in those days was the center of in-depth research on the USSR, especially on its military capabilities and strategies, and its staff included many of the most notable names in national security research.

Alex started as a junior intern, but rapidly worked his way to become a senior analyst and project director. His clients included offices in the Pentagon, in particular the Office of Net Assessment run by the famous “Yoda,” Andrew W. Marshall, for whom Alex completed many projects on all aspects of Soviet intentions and capabilities. Other clients included various agencies of the American intelligence community and most of the branches of the armed services. The subjects of his research covered military and foreign affairs related to NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. He also delved deeply in the implications of demographic change, the forces of nationalism generally, and the dynamics of ethnic and religious conflict in many places.

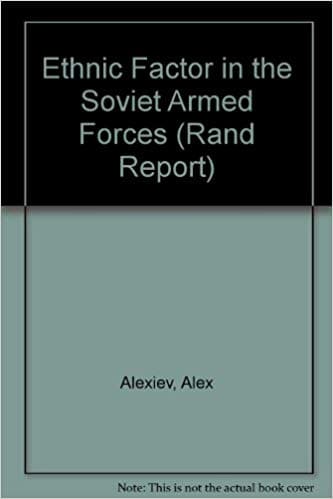

Of particular note was a pioneering study in which he played a leading role to examine the characteristics, dynamics, and consequences of the ethnic factor in the Soviet armed forces. This is where his own experience in construction battalion full of minority soldiers was formative. Drawing on the first-hand experiences of recent émigrés from the Soviet Union to many countries around the world through extended one-on-one interviews, Alex and his colleagues produced a pathbreaking study on the costs and benefits of the Soviets attempting to sustain a large multi-ethnic presence in their armed forces. Moreover, in the course of the study the interviewees revealed factual and anecdotal information about Soviet military capabilities and conditions and terms of service that could not be found by analysts reading Pravda or even specialized Soviet publications. The impact of the study on the American analytical community was notable, and it resulted in many new approaches to the study of the USSR’s military prowess. And of course its general thrust—that ethnic diversity in the closed Soviet system was a substantial liability—was borne out powerfully when the USSR collapsed in 1991.

Between 1984 and 1992, Alex was a faculty member of the Rand/UCLA Graduate School for Public Policy. On leaving Rand, Alex turned his attention to the private sector, providing consulting to major U.S. and European corporations and investment banks on Russian and Eastern European markets, investment, and privatization strategies. He also consulted on bond and equity markets in Russia, Eastern Europe, Turkey, Indonesia, and other emerging markets.

In 1990-1991, Alex was lured back to Munich by the excitement of communism’s collapse in Eastern Europe and the USSR to become director of Radio Free Europe’s broadcast service in Bulgarian. It was short stay, probably because the excitement was indeed great. In 1992, Alex returned to Sofia, where he served as the Principal Advisor (pro bono) to Bulgaria’s first democratically elected prime minister, Philip Dimitrov. From that time until his death, he would reside in Bulgaria full- or part-time.

During the years after 1992, Alex engaged in business in Bulgaria, and he began the process of retrieving the family properties the communist regime had stolen from his family. He traveled often between Bulgaria and the United States, especially to his small ranch in Templeton, California. This miniature paradise was ideal for Alex’s additional passion of agriculture. With his wife Laurie and young family—Renee, Alex, Eric, and John—he tended 800 olive trees, a small vineyard, and a large and productive vegetable garden. Their parties in Templeton were legendary, fueled by wonderful food, high intellectual discussion of foreign policy that often descended into limericks and laughter, and, of course, Alex’s wine.

In 2002, Alex served as vice-president for research at the Center for Security Policy in Washington, DC, where he directed national security research focused on Islamic extremism and terrorism. This subject was to consume him for the rest of his life.

Alex was a man of strong opinions, but his opinions were always backed by a stubborn empiricism. Few researchers could hold a candle to his analytical labors across a wide spectrum of sources: written, digital, or human. His curiosity was insatiable. He was often seen by the more flexible academic types as hardline and hardnosed. When he was right—as he nearly always was—he was both. Alex backed up his conclusions with hard data and deep research. Those of us close to him learned early on not to doubt what often seemed his rampant speculations; later, his insights would gradually or suddenly become clearer, and they were often profound. He was ahead of his peers on every subject he chose to immerse himself in, often far ahead.

The Center for Balkan and Black Sea Studies and, especially, Bulgaria Analytica are the capstones of Alex’s long and distinguished career. His time there is best told by those closest to him, like his dear friend and collaborator Ilian Vasillev. His last few years were occupied by resurrecting the memory and history of his distinguished father, assisted by son Eric. In these ventures, his dream of serving his native land came full circle. He wanted to finish where he began. As always, he did so with typical passion, intuition, and humor.

Alex Alexiev made the world a better place, and he made all of us who knew and loved him better people. He was a significant figure in his moment. Shakespeare wrote in As You Like It of people who “have exits and entrances, and one man in his time plays many parts,” alluding to the impermanent nature of our time on earth and the many roles one has yet to play. One suspects the great bard was thinking of Alex, who, somewhere, has embarked on a new role to take us all to a higher level.

* S. Enders Wimbush a distinguished fellow at the Jamestown Foundation in Washington D.C. and a former director of Radio Liberty is a member of bulgariaanalytica’s board of international advisors.