As Western sanctions began to bite, Iranian government rewarded IRGC with huge contracts in oil business; the IRGC also enjoys other competitive advantages which will be even more useful as sanctions recede.

Reuters –

VIENNA – Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guards have done very well out of international sanctions – and if a nuclear deal is done in Vienna this week under which those sanctions are lifted, they are likely to do better still.

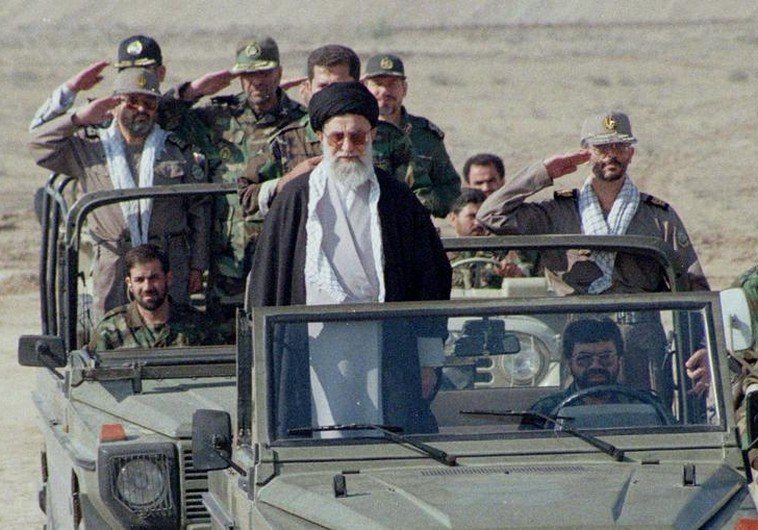

The Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), created by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini during Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, is more than just a military force. It is also an industrial empire with political clout that has grown exponentially in the last decade, benefiting from the favor of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, himself a former guardsman and, most recently, from the opportunities created by Western sanctions.

A Western diplomat who follows Iran closely told Reuters that the IRGC’s recent annual turnover from all of its business activities was estimated to be around $10-12 billion.

Iranian officials refuse to reveal the IRGC’s market share, but $12 billion would be around a sixth of Iran’s declared GDP, at current exchange rates.

“They control major companies, and businesses in Iran such as tourism, transportation, energy, construction, telecommunication and Internet,” said an Iranian official in Tehran who asked not to be named.

“Lifting sanctions will boost the economy; it will help them to gain more money.”

It was the IRGC, unquestioningly loyal to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, that suppressed student protests in 1999 and also silenced the pro-reform protests that followed Ahmadinejad’s disputed re-election in 2009.

That year, a company affiliated to the IRGC bought the state-run telecoms company for about $8 billion.

Soon afterward, the United States and European Union slapped new sanctions on Iran’s oil and finance sectors, in a bid to force Iran to curtail a program that it said was peaceful but they argued could be used to develop nuclear weapons.

As these sanctions began to bite, it was the IRGC that was asked to take up the business of the European oil firms that had been forced to pull back.

“The government rewarded them with huge no-bid contracts. Their front firms were named the winners of most of the bids,” said the head of an oil consulting company, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Competitive advantages

The IRGC’s construction arm, Khatam Al-Anbia, thought by many to be Iran’s largest company, is developing parts of the giant South Pars gas field, and has a $1.2 billion contract to build a line of the Tehran metro and a $1.3 billion contract to build a pipeline to Pakistan.

But the IRGC also enjoys other significant competitive advantages, which will be even more useful as sanctions recede.

“Lower insurance, shipping, and commission costs with the banks will also enable the Guards to freely import spare parts, equipment, and technology from international companies,” the Western diplomat said.

An Iranian trader based in a Gulf country who does business with some IRGC-affiliated firms said the Guards’ control over terminals in Iranian airports and ports helped them to move commodities in and out without paying duty.

Much of the IRGC’s business is done through front companies, many of them not even formally owned by the Corps, but by individuals and firms linked to it.

“For a few years now, the IRGC has been buying small and medium-sized companies in Iran and using them as front companies,” the trader said.

To do business in Iran, foreign companies need an Iranian partner, which for large-scale projects often means firms controlled by the IRGC.

Analyst Hamid Farahvashian said many of these front firms were not known at all, “and will be used for the time when sanctions are lifted to work with foreign companies”.

And that might, for instance, allow the Western oil firms that Iran wants to lure back to do business at arm’s length with Khatam al-Anbia, which is designated by Washington as a “proliferator of weapons of mass destruction”, and has at least 812 affiliated companies.

“Companies should be careful when signing contracts because they’ll never know who’s really behind those companies,” the Western diplomat said.

Unlike some parts of Iran’s hardline establishment, IRGC commanders have publicly backed the principle of a nuclear deal, which would anyway be impossible without Khamenei’s support.

Good reasons

“The establishment backs the deal. Khamenei has supported the negotiations. Therefore, the IRGC, which is loyal to the leader, could not reject it,” said analyst Saeed Leylaz.

But the IRGC has good reasons of its own to welcome the deal, beyond the mere prospect of economic growth and contracts with the foreign firms now queuing up to invest in Iran.

For all its skill in circumventing trade sanctions, for instance by trading through third countries, some of the restrictions have begun to prove insurmountable.

“The IRGC-affiliated companies lacked the technology and knowledge and ability to carry out projects,” said a former Iranian official, who asked not to be named.

“Basically, sanctions were gradually making it impossible for even the IRGC to make money. That is why they support lifting sanctions – then they will earn money through their subcontractors when the economy flourishes.”

This does not mean there is no nervousness within the IRGC at the prospect of the economy opening up.

Iran’s pragmatic president, Hassan Rouhani, has made much of the economic revival that an end to sanctions promises, and has been seeking to stimulate the growth of a genuine private sector, currently utterly overshadowed by state-controlled firms. Some pro-reform politicians have accused IRGC-affiliated companies of mismanagement and criticized them for delays.

“The IRGC is not a monolith. Some feel threatened by a deal that could open up the Iranian economy and force them to compete with major international companies,” said Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

For now, however, there is little or no sign that the political backing that the IRGC enjoys will fade, as Iran’s leaders publicly praise its role in managing Iran’s oil industry.

Ahmadinejad has gone, but other former guardsmen hold significant positions, including the secretary of the Supreme Council of National Security, Ali Shamkhani, and parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani.

“Boosting the economy will increase the IRGC’s influence over politics and the economy because it will strengthen the hardline establishment,” said one Iranian oil executive.