|

إستماع

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Exactly one hundred years after the birth of the Soviet Union on December 30, 1922, we could well be witnessing its second collapse. Putin’s attempt to reconstitute a privileged sphere of influence around Russia is turning into a catastrophe. And this catastrophe may only be the beginning. It is becoming increasingly difficult to see how Russia can emerge from its Ukrainian adventure on top. The word “historic” is often overused to describe current geopolitical developments. But sometimes it is well deserved.

On the path toward fascism?

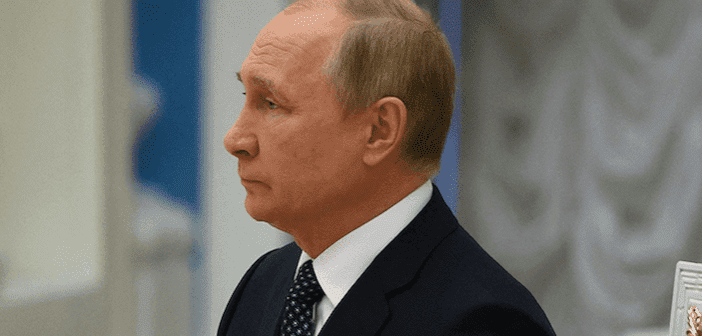

Former French diplomat Michel Duclos accurately described the radicalization of Russian politics since Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012: “creeping color revolutions, a neo-colonialist desire to keep control of the ‘near abroad,’ a sense of opportunity, a perception of the West’s weakness, and a desire for international assertiveness“… and the emergence of a potential partnership with China. This outward radicalization, accelerated by Kyiv’s drift towards the West, and coupled with domestic stiffening – the two feeding off of each other – escalated since the end of February. To speak today of a “totalitarian” state would be excessive. There is neither absolute control of society nor its complete mobilization in Russia today. And many citizens seem more interested to flee from the war than to join it. But speaking of a regime that is turning into fascism is becoming less and less absurd. Vladimir Putin appears to be increasingly overcome by his far-right. His strategy of co-opting violent, even neo-Nazi groups in the 1990s – to protect the country from democratic contagion – is turning against him.

The ground was definitely fertile. Contemporary Russian political culture is marked by a de facto alliance between men from the security service (siloviki) and men from organized crime. The army embodies these ties in an even stronger manner due to the very structure of Russian armed forces: soldiers are often left to their own devices because of the weakness of the non-commissioned officers, and officers whose military culture has been forged by “counter-terrorism” operations in Chechnya (1999-2009), or more recently in Syria: an unleashing of indiscriminate violence devoid of any moral concern.

Chechen and Russian militias – the Wagner Group stands out – now hold the upper hand (before turning it into an iron fist?). The Russian ultranationalists used to be relatively marginal figures. “These characters (…) were satisfied to rant about nuclear war fantasies on TV. The novelty, from now on, is that they have private armies, with artillery and aviation, and a blood-stained mace as their emblem“. One must carefully read the national address given by the Russian President in the regal St. George’s Hall of the Grand Kremlin Palace, on September 21, to celebrate the annexation of four Ukrainian oblasts. It is filled with references: the glorification of the past, mentions of Anglo-Saxon enemies, a promised bright future, and quotations from the philosopher Ivan Iline… All of which are troubling clues. They add to the cult of the leader, the emphasis on alleged past humiliations, state capitalism or Putin’s remarks on the “purification” of Russia that would result from the exodus that followed the launch of Operation Z.

The alliance between the Orthodox Church and Putin also reveals disturbing rhetorical excesses. During the September 21 celebrations in Red Square, a character dressed as Doctor Strangelove from the film of the same name was seen speaking. Ivan Okhlobystin, an actor and defrocked priest, thanked God that Russia “could no longer go backward“, and described the ongoing war as a “confrontation between Good and Evil, between light and darkness, between God and the Devil, (…) a holy war” that every Russian is called upon to begin “in his heart, against his own sins“. The same words as well-known ideologist Alexander Dugin, for whom “the last battle of light and darkness” has begun. Those who see here only the excesses from a loud minority would benefit from reading the once more nuanced experts such as Dmitri Trenin, who see the war as an opportunity to overcome “primitive materialism and lack of faith”. An isolated point of view? Not according to some of the experts on Russian culture, who see a direct link with the nihilist tradition of the end of the 19th century, for which destruction is not “a means but an end in itself“: it would be purifying and redemptive.

The second collapse of the Soviet Union

In Serheii Plokhi’s pithy formulation – one that mimics Lord Ismay’s famous quip about NATO – the Soviet Union ensured to keep “the Ukrainians in, the Poles out, and the Russians down“. Today, Putin’s neo-imperial project is collapsing. Not only has he failed to unify the Russian world (russki mir), but his closest neighbors, thanks to the war, now seem to want to emancipate themselves.

After having briefly called on Moscow for help to quell a nascent revolt, Kazakhstan decided to distance itself from its large neighbor. Moreover, Russia is no longer there to restore stability in its neighborhood. Because it was absent during the last clashes between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan (even though it had brought calm there in 2021), Bishkek canceled the joint maneuvers that were to take place with the Russian army.

Above all, Moscow turned a deaf ear when Armenia, whose sovereign territory was attacked for the first time by Azerbaijani forces, invoked last September the defense guarantee contained in the founding treaty of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), NATO’s substitute. As a result, Yerevan refused to sign the final document of the November 2022 CSTO meeting, which may have been the death warrant for the organization.

Can we speak of simple aftershocks of the 1991 earthquake? It is at least what former French ambassador Gérard Araud called the “second war of succession of the USSR“. And it probably goes further. In addition to the CSTO, the other pillar of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Eurasian Economic Area (EEA), is also in a bad shape. Moscow was never really serious regarding regional multilateralism and cooperation among equals. Today, not only is its hard power in decline; its soft power is too. And Russia’s forced annexation of four Ukrainian oblasts provoked more fear among Moscow’s neighbors than respect for the former tutelary power.

Economic dependence ties (especially with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) will not disappear overnight. Nor will the status of immense Russian territory as a migratory crossroad. We are familiar with what Zbigniew Brzezinski famously observed: without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire. This will be especially true if Moscow’s loss of influence in the rest of its environment is confirmed. Hence, we may be witnessing “the twilight of Russian imperialism” in the coming years. In Central Asia and the Caucasus region, other powers will take advantage of this, starting with Turkey and China as well as, if they play their cards well, Europe and the United States. Without, however, having the capacity and the will to serve as the region’s policemen – a role that Moscow assumed (it must be said) quite well. A new Great Game can begin…

The final downfall

In the best-case scenario for him, Vladimir Putin would manage to present his very likely defeat in Ukraine as a “win”. Isn’t this what Khrushchev did after the Cuban crisis, or autocrats such as Saddam Hussein, the latter presenting his pitiful withdrawal from Kuwait as such? Nevertheless, he will have a hard time convincing Russian public opinion that experienced a decade of brainwashing but is not totally apathetic.

Let us propose three (near-)certainties and four scenarios. First certainty: Russia in the mid-2020s will be a country undermined by military, economic (sanctions) and demographic weakening (more than 500,000 people have already left the country). Second certainty: the country is separating from Europe. Ukraine was the “western side” of the Russian body, balancing its “eastern side”.

Without it, whose influence on the history and formation of Russian elites is sometimes overlooked, the Mongol and Tatar heritage of Russia will take a more important part in the national culture. The third certainty is that after the war, Russia will enter a troubled period. We know the history of the country: military debacles are often followed by political upheavals, as we saw in 1905, 1917 or 1989.

As for the scenarios, the least unfavorable one would be that of Germany after 1945. After the Götterdämmerung, the Stunde Null of which ensued shock and trauma, then followed by introspection and healing. But Russia does not have the rule of law tradition (even with interruptions) that Germany had at the time. Not to mention that it will be difficult to put it through a Nuremberg. And the country will not be placed under the protection of a benevolent protector…

More likely, then, is the North Korean scenario: the isolation and radicalization of a fortress-Russia, in which Putin or his successors would keep the country’s population in a permanent state of war. French expert Françoise Thom speaks of an “autarkic empire” that would wean the population away from Western influence. She quotes the writer Dmitri Gloukhovski, who evokes a Putin weaving “a cocoon in which Russia will have to wrap itself to hibernate for decades, even centuries“, as well as the historian Vladimir Pastoukhov, who imagines a “frozen body“, “locked in a gigantic cryogenic chamber the size of one-seventh of the land surface“.

A step further in the pessimism scale, Russia would become (for those who are most worried) a kind of Mordor (“black country”), a desolate land in which the forces of evil are preparing their revenge and reconquest of Middle Earth. The country’s descent into barbarity is already at work, according to J.R.R. Tolkien fans, who are comparing the behavior of the Russian military to that of the Orcs, those half-beast half-human soldiers capable of the worst. An exaggeration? Not really, if you realize that for the past ten years, Russia’s best and brightest brains have left and, increasingly, so as its middle classes. But Russian society has become criminalized “groups have taken over mafia rules, borrowing from them a lifestyle, physical attitudes, a sui generis ‘morality’, a hierarchy formed by ‘godfathers’ ruling over their protégés“.

Could the Russia of this new “times of troubles” (smutnoye vremya, the anarchy of the early 17th century) resemble, in the extreme, Somalia in the 1990s, in which militias and gangs would rule, their recruitment pool fed by the return of bitter conscripts, many of whom were former prisoners?

Russia’s breakup?

As has been pointed out, the Russian empire, given the distances between the core and the periphery, actually resembles its European counterparts of the past. Could Russia survive the collapse of the national myth fostered by Moscow, that of a tutelary nation superior to others and destined to control its neighbors?

The Somalian scenario would also be that of the breakup of the Russian nation-empire.

In minority republics, revolt is already growing. One has to recognize that the Buryats, Tuvans and other Dagestanis, who make up a disproportionate share of the Russian army (as drafting represents social ascension in these poor regions) have, as in any empire, paid more blood money than ethnic Russians. And while Mr. Putin – to his credit – has never despised the country’s Muslims, favoring a “national” rather than “ethnic” conception of his country, what place would Islamist movements take in a Russia where anarchy reigned? But the disintegration could also begin in distant and rich regions, like Slovenia for Yugoslavia…

“Great empires do not go gracefully into oblivion” warned the US ambassador to Moscow in early 1991. In the United States and in Europe, the same debate as 30 years ago would reappear: should one prefer the dissolution of the country and its weakening (as did US Vice President Dick Cheney), or its permanence in view of its nuclear status (that of US Secretary of State James Baker)?

Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen wrote about Germany in June 1941 stating: “never has a people staggered towards catastrophe in such a state of stupefaction and impotence“. For Françoise Thom, whose analyses have often been judged too pessimistic but to whom history seems to be right today, this sentence applies perfectly to contemporary Russia.

There is little reason to rejoice. But if the above analysis is correct, it means that Europe and Russia are likely to be separated for a long time (provided that the former can reduce its dependence on Russian gas to a minimum). This may be the end of a three-century historical cycle, which began with the victory over Sweden at the Battle of Poltava (1709). As Ukraine enters Europe, Russia leaves it.