(Note: This piece was written before the terrorist attack in Jerusalem on January 27.)

“I expect we’ll see an agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia this year,” said former ambassador to the United Nations and Likud party Knesset member Danny Danon back in December 2022, soon after Benjamin Netanyahu had formed the government. Danon was echoing Netanyahu’s previous statements—made before and after the November 2022 elections in Israel—which stressed the importance of the Abraham Accords and, in particular, his interest in normalizing relations with Riyadh.

However, the nature of the current coalition is quite radical, consisting of the most far-right elements of the Israeli political map. They promise to speed up settlement construction in the West Bank and are calling for the “elimination of those who finance terror,” referring to the Palestinian Authority (PA). The situation on the ground in West Bank remains shaky at best. Consequently, there are many questions regarding the existing peace agreements between Israel and the Arab world, as well as any future agreements. Will Netanyahu find the desired equilibrium between the radical politics of his coalition partner and diplomacy with Arab capitals?

Same coalition, different goals

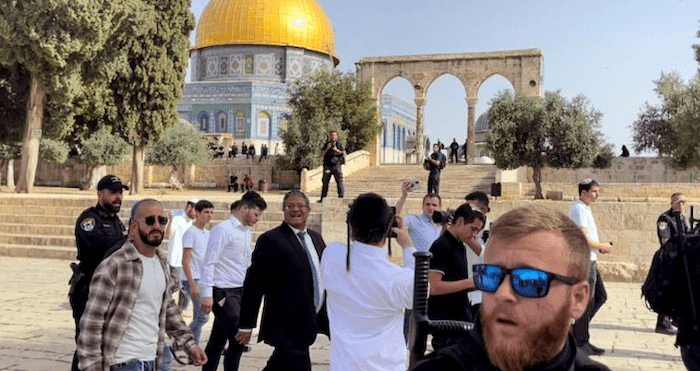

The first visit of Itamar Ben-Gvir, the newly-appointed minister of national security to the Temple Mount—also known as Haram al-Sharif (Noble Sanctuary), which is a sacred site for Jews and Muslims—lasted merely thirteen minutes. The aftertaste of the January 1 visit, however, was felt for much longer. Ben Gvir, who is the leader of the extreme-right Otzma Yehudit party, has previously been convicted for supporting terrorism and inciting racism. In the last few years, he actively campaigned for the freedom of worship for Jews on Temple Mount. As minister of national security, Ben-Gvir oversees the police in Israel as well as some police activity in the West Bank.

Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Morocco, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as well as many other countries, have strongly condemned Ben-Gvir’s visit. Meanwhile, Thomas Nides, US ambassador to Israel, said that the Joe Biden administration has made it clear to the Israeli government that it opposes any steps that could harm the status quo in the holy sites. Netanyahu’s planned visit to Abu Dhabi during the second week of January was subsequently postponed by the Emiratis. Additionally, the UAE, along with China, called for an urgent meeting of the United Nations Security Council on January 4 to discuss the tensions in Jerusalem.

While Israeli media initially reported that Ben-Gvir was considering postponing his jaunt to the Temple Mount until after Netanyahu’s first state visit to Abu Dhabi, the ultranationalist minister was determined to promote his own goals and please his ultra-right-wing electorate. Whether Netanyahu believed Ben-Gvir’s visit would be quickly forgotten—thus, underestimating the reaction in Abu Dhabi, Amman, and Rabat—or whether he was unpleasantly surprised by the harsh response of the Arab world, there is no doubt that his minister of national security had the upper hand.

Although Netanyahu might be dreaming of rapprochement with Saudi Arabia—and possibly winning the Nobel peace prize—Ben Gvir and his followers are eyeing a different kind of gain: promotion of the freedom of worship for the Jews on Temple Mount, settlement expansion, and the curtailing of human rights organizations in the West Bank. The end goals of the prime minister and the minister of national security couldn’t be more different.

New Middle East, old Middle East

What will happen next when Ben-Gvir and other members of Netanyahu’s coalition push their policies forward, as designated in recent coalition agreements? On January 6, the Israeli government decided to sanction the Palestinian Authority for waging a diplomatic battle in the United Nations following Ben-Gvir’s visit. Under this pretense, all previous policies of the Naftali Bennett-Yair Lapid government, which were designed to strengthen the PA and avert its collapse, have been undone. PA revenues will be withheld; building permits in Area C—the largest section constituting about 60 percent of the West Bank territory and its only contiguous section, which was supposed to be gradually transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction according by Oslo Accords—will be revoked; and VIP benefits, such as crossing passes to Israel, will be canceled. Such actions will help boost Hamas and other extremist Palestinians groups’ presence in the West Bank.

How will Arab states—those who maintain normal relations with Israel as well as those who don’t—react to these and other policies? What will happen if the PA collapses and conflict reignites in the West Bank (and, specifically, in Jerusalem)? The UAE, Bahrain, and Morocco signed the Abraham Accords with Israel while the situation in the West Bank was tense but relatively stable. The accords also survived the turmoil in May 2021 and in July 2022, although their popularity in the Arab street soon begun to wane. Now, after a turbulent week of condemnations and UNSC discussions, it seems that things are returning to normal.

The Negev Forum—a multilateral regional forum launched by the Biden administration and seven regional governments—met in Abu Dhabi on January 9-10 to discuss regional integration. Similarly, earlier in December 2022, the Atlantic Council’s N7 Initiative convened Israeli and Arab experts on education and cultural exchange in Rabat, Morocco—the first in a series of conferences aimed at strengthening regional cooperation. The past year was particularly successful, as bilateral trade between Israel and the UAE grew exponentially; extraordinary defense MOUs were signed between Israel, Morocco, and Bahrain; Israeli-Egyptian cooperation on gas exports reached new heights; and Israel and Jordan concluded a long-awaited water-for-electricity deal.

It would be unimaginable if all this progress was thrown under the bus over just one provocation, even if it infuriated and worried many. One might also recall that the peace deals between Israel, Jordan, and Egypt survived even tougher times, including the 1982 war in Lebanon and the second intifada in 2000. But embassies were vacated, economic cooperation decreased, and diplomacy suffered, nonetheless.

At the same time, the Abraham Accords require a stable environment to thrive. If conditions on the ground change for the worse, it might also impact the degree of closeness and warmth between countries—not abruptly, but over time. If the Israeli government renews its interest in annexation or acts recklessly in Jerusalem, it will eventually find out that the “new” Middle East of the Abraham Accords is quite similar to the “old” Middle East of condemnations, hostility, and mistrust. If the Arab countries—which risked departing from the traditional policy of no normalization absent a solution to the Palestinian conflict—come to see Israel as a reckless and irresponsible partner, much of this progress might be reversed.

The Saudi card

Talking to the Washington Examiner on December 16, 2022, Netanyahu said that a peace deal with Saudi Arabia would “effectively end the Arab-Israeli conflict, not the Palestinian-Israeli conflict but the Arab-Israeli conflict.” Speaking to the Saudi Al-Arabiya TV channel on December 15, 2022, he explained that the peace deal with Riyadh might “bring peace with the Palestinians,” trying to tie together his aspiration to advance Israeli-Saudi normalization with Riyadh’s desire to advance the two-state solution. The logic here is clear: give us the key to Riyadh and we might—or might not—make some advancement on the Palestinian track, which will be more possible as the Palestinians will be pressed against the wall.

Israeli media is currently abundant with hints that peace with Riyadh might be closer than one might think. A recent piece by John Hannah, a senior fellow at the Jewish Institute for National Security of America and former national security adviser to Vice President Dick Cheney, discussed possible Saudi conditions for such a move, as articulated by a senior Saudi figure. All conditions had to do with security guarantees by the United States, and not one focused on resolution of the Palestinian issue.

Yet, for now, the Saudis have made sure to articulate their traditional position: the Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital is a requirement for peace with Israel. This was echoed by Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir to CNN in July 2022. During Ben-Gvir’s recent visit to the Temple Mount, the Kingdom not only condemned the incident, calling it a “brazen provocation,” but again reaffirmed Saudi Arabia’s “solid stance of standing by the brotherly Palestinian people,” further voicing the Kingdom’s support of all efforts which aim “to end occupation and reach a just and comprehensive solution…to allow the Palestinians to establish an independent state along the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital.”

It’s a well-known fact that the economic potential for cooperation between Israel and Saudi Arabia is enormous. Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s de-facto ruler Crown Prince Muhammed Bin Salman (MBS) looks at Israel in a more favorable light than his predecessors. Yet, the Saudis keep signaling that the grand deal will require a departure from current Israeli policy, certainly not a turmoil du jour. “We don’t look at Israel as an enemy, we look to them as a potential ally, with many interests that we can pursue together… But we have to solve some issues before we get to that,” MBS said to the Atlantic in March 2022, indicating that, although the obstacles are not insurmountable, they cannot be pushed aside entirely.

It’s still unclear whether Prime Minister Netanyahu will be able to drive his unruly coalition in the right direction. While he is interested in reaching Neom, the futuristic Saudi city on the shores of the Red Sea, his ministers would rather build another settlement in the West Bank. As things stand right now, the new Israeli governing coalition is still being scrutinized by the Arab world. Warnings have been made and signals have been sent. Any policy changes will not be taken lightly, as the Arab countries have much to lose, both economically and reputationally. However, if the situation spirals out of control, particularly in Jerusalem, the warm peace might get colder and the normalization process—possibly the only bright spot in an otherwise troubled region—will be stalled.

Ksenia Svetlova is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs, and is the director of the Israel-Middle East Relations Program at Mitvim. Follow her on Twitter: @KseniaSvetlova.