How two researchers got to the heart of a polling problem: the skewing effect of fear.

Growing up in my household, secular was a slur, the thing you became if you lost your faith, or if you were selfish. I come from a family of religious individuals. Not a religious family, but a family that happens to include many faithful people, Muslim and Christian. In Iran, where my mother was a Christian convert, and later in the American South, I grew up with faith all around me. In my native home in Isfahan, I wore a hijab and went with my mother to a secret underground church. As refugees in Dubai and Italy, we sang hymns with other asylum seekers on somebody’s untuned guitar. As an adolescent in Oklahoma, I wore a “True love waits” ring and a “WWJD” bracelet because that was the fashion among the devout teenagers with whom I ate lunch. Did I believe then? Probably not. I did what I was told. And I didn’t want to eat lunch alone.

Still, every few months when I was a girl, I’d find myself sitting around a tea tray or a dinner table with travelers from home, tired second cousins or uncles or acquaintances from Tehran or Isfahan. Inevitably, they would shake their heads and say, “Iranians back home aren’t that religious, you know.” At first, I didn’t believe them. And anyway, I thought, they’re just talking about Tehrani academics. I was an analytical kid, and even then I had some idea ofbiases in observed data. Besides, my extended family is Muslim on both sides, some devout, some secular; the adults often debated issues of faith. If Iranians weren’t religious, I thought, with my teenage understanding, why would they have a religious government, and why would we have had to flee our home and break up our family because of our apostasy?

Those events are decades old now. Postrevolutionary Iran and I are both in our 40s, and we’ve both grown and changed. This will be as difficult for Americans to believe about Iran as it has been for my mother to believe about me, but we’re both astonishingly secular now.

Iranians are always joking about the dusty, unopened Quran everyone keeps on their coffee table to wave around in case the morality police stop by. In academic discourse and mountainside conversations and dentist’s-office chats and afternoon gossip, they have been whispering and debating and shouting to one another about secularism and faith for a while now. Among exiled academics in Europe and the U.S., the debate about the Iranian population’s underlying beliefs is nearly as heated. The possibility of western intervention makes the topic fraught for those outside Iran — after all, we’re not the ones who will suffer the consequences of food shortages, crackdowns, or war. As progressives, we want to respect people’s right to self-determination, we want to fight economic colonialism, and we don’t want to harm people with sanctions. It’s easier to believe that a country like Iran has decided to be Muslim, that everyone is happy with that. But is Iran really a country of devout people, or have many, until now, just kept their nonbelief to themselves in order to be safe?

It’s absurd to deny that Iranians are rejecting their government. On September 16, 2022, a 22-year-old woman named Mahsa Zhina Amini died in police custody. The women and men of Iran spilled into the streets, coming together in a feminist uprising the likes of which Iran has never seen. It is a thrilling moment to watch for a person who spent three formative years forced under hijab. I remember the scratch of the maghnaeh against my neck, the slap of the ruler against my palm when my hijab slipped off, the chador-clad teachers watching us from every corner of the blacktop, the Ayatollah mural looming over our heads as we played jump rope and hopscotch. I can still feel the pimply rash above my forehead from sweating under the taut fabric. And I’ve watched my mother be berated by moral police for letting her hijab slip one inch past her hairline.

But I refuse to misinterpret the moment. Iranian women aren’t looking for hijab reform or concessions on gender laws. They’re leading a revolution. The people of Iran don’t want to live under Sharia or any religious law.

It would be easy to think, watching so many brave Gen-Z and millennial women take to the streets, or looking online at the fiery doctors, lawyers, rappers, and students, that Iran suffers from a generational divide rather than a shift in national thinking. But talking to older people back home, I hear regret from those who marched in the Iranian revolution in 1978. “What did we do to our children?” one asks. I remind him that they didn’t want the Islamic Republic; that was an outcome they couldn’t predict. My father sends me voice memos from Iran. He peeks through his office window at the women in the streets and calls them brave. “We gave them so little,” he says. Then he repeats the advice he has offered me for decades: “Always trust science, Dina joon. Science and poetry. Superstition ruins lives.”

There’s a fascinating anthropological case study called “The Deep Believer,” by Reinhold Loeffler, who followed a highly religious Shi‘a villager, Husseinkhan Sayadi, in western Iran for decades until the villager’s death in 2008 at 82 years old. The two men became friends. In the report, Loeffler cites his friend’s loss of faith over many years: “Who knows anything about the working of God? … Paradise? That also has been made up for the deception of people. Yes, once I had a very strong belief in those things, and if Khomeini had not come, I would still today have this belief. But now I have seen examples of their doing. The prayers the mullahs are saying benefit no one.”

But case studies and anecdotes aren’t enough. How do you measure overall religiousness in a place like Iran?

Years ago in Amsterdam, I met an academic, Pooyan Tamimi Arab (a distant relation), and his wife, Sara Emami, a visual artist. We talked about philosophy and Iranian history, about Arendt and Spinoza and the role of the state. In 2009, we went to demonstrations in Amsterdam in support of the Green Movement. When I moved away, we lost touch except when our work overlapped. Then I heard about a project he had taken on: Tamimi Arab had joined Utrecht University as an assistant professor of religious studies and was helping a Tilburg Law School colleague, political scientist Ammar Maleki (a major political commentator in Iran), to measure religiousness in the Iranian public. Tamimi Arab too had wondered what the Iranian people really wanted. All official data showed a highly religious country, but every day he saw memes on Iranian social-media channels, hopeless people describing their country as a mullahcracy.

In 2019, the two scholars created an organization called GAMAAN (Persian for “opinion” and a loose acronym for Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran) and designed a lifestyle-and-values survey. Their questions were similar to those of the prestigious World Values Survey, which is conducted globally in or near people’s homes and is widely trusted. Their hypothesis was that, while the WVS followed accepted traditional polling and data-analysis practices, it wasn’t getting the truth on religious belief out of respondents in Iran. Why? Because random sampling requires people’s contact information. It is often done by telephone or in person by local subcontractors who need the government’s permission. And what citizen of an authoritarian theocracy, when asked by a strange caller how religious they are, is going to say “Not at all?”

This seemed to me an excellent point.

Researchers in Tunisia, China, and Russia have run into similar bias problems when conducting telephone polling inside those countries. “Iran is an extreme context,” Tamimi Arab told me, “but in other countries like Tunisia, which is not as extreme, researchers have found that people are scared of the military.” In the study “Who Fakes Support for the Military?” researchers Kevin Koehler, Sharan Grewal, and Holger Albrecht warned, “We find that misreporting of support for the military in Tunisia is substantial, with respondents overreporting positive attitudes by 40–50 percentage points.”

One simply can’t conduct an open survey about religion inside a brutal theocracy that kills people for going secular.

But Gallup, Pew, and WVS had all said the Iranian population was wildly religious, and the western public believed them. They were the experts, after all, trusted and meticulous. And who has time to scrutinize expert data? From February to May 2012, Pew conducted face-to-face surveys of Iranians, and in 2013 it reported that 83 percent favored Sharia in Iran. Many Iranians saw “face-to-face” and laughed — conducted three years after the 2009 Green Movement, Iran’s biggest uprising since the revolution, Pew’s survey was devoid of a context that, left ignored, had doomed its methodology.

If respondents who were terrified of the regime were lying to big established survey institutes like Gallup, Pew, and WVS, as GAMAAN’s founders suspected, how would two academics in the Netherlandsget the truth out of the Iranian people?

A word on polling and opinion surveys in the 2020s: In order for a small sample of a population to be statistically representative of the whole, it must be truly random. In traditional probability surveys, random samples were collected through telephone calls. Gallup, for example, would generate a list and keep calling those specific people until a significant portion had responded. What kept the data fairly accurate was the relentlessness of the interviewers, who chased the same respondents so they couldn’t self-select and skew the data. Still, non-responsiveness has always been a problem, and researchers correct for self-selection by weighting the data so it matches the population on demographics like age, gender, and education. But with fewer people answering home phones or listing themselves in telephone books, with households often having several numbers, and with the advent of the internet, telephone polling has become less reliable and much more expensive. Many peer-reviewed and highly respected researchers now use non-probability surveys; they conduct surveys online, allowing respondents to opt in. Opt-in surveys are cheaper and faster, but most important for a country like Iran, they are anonymous. Ensuring anonymity corrects for one of the biggest failures of random methods in a theocracy: the skewing effect of fear.

Ensuring anonymity also means the researchers can’t vet the data, responses aren’t random and often require a much larger sample size, and they must go through a process of data correction (for data quality and diversity) to get anywhere near the truth. So GAMAAN started using social media to target literate people over 19 years old from diverse layers of Iranian society (which they extended to pro-regime channels), reassuring them that the online survey data would remain anonymous. They started in 2019 with a simple poll, a single question for the 40th anniversary of the revolution: “Islamic Republic yes or no?” They advertised it via Instagram, Telegram, and other channels to make sure they attracted respondents from every stratum and location. The survey went viral with around 200,000 responses, 180,000 of them inside Iran. Of this total, 79 percent said that if there were a referendum today, they would not choose the Islamic Republic. In response, the Islamic Republic blocked the SurveyMonkey app in Iran.

Although the researchers had expected pushback from pro-regime factions, immediately there were detractors in media and academic circles, too. GAMAAN’s critics pointed out that online polling is in its infancy and that you can’t do snowball sampling (relying on people to pass the survey around) with much accuracy. Maleki and Tamimi Arab countered that they had gone viral through many different channels — it was more like 50 snowballs in diverse communities. Some researchers said that if GAMAAN had come up with a different answer than PEW and Gallup, it was because the responses were bots, self-selecting radicals, or foreigners. But GAMAAN had corrected for these using bot-detecting software, location filters, and demographic data to make sure it sampled people from all walks of Iranian life: rural and urban, young and old, educated and uneducated, and across the political divide. GAMAAN then invited a senior researcher from Pew to take a look. He was impressed and invited Maleki and Tamimi Arab to present their work in Washington, D.C. Pew doesn’t comment officially on other surveys, but the researcher did confirm to me that GAMAAN had followed Pew’s recommendations for adjusting non-probability data in order to be representative of the population.

In 2020, GAMAAN created a longer, more complex religion survey. Again, it reached out to people with diverse demographics matching the nation. It paid particular attention to groups that had not responded in 2019 and made sure that the language and images in the ads resonated with each target group. Supporters, including the journalist and women’s-rights activist Masih Alinejad, shared it on social media, encouraging their followers to participate.

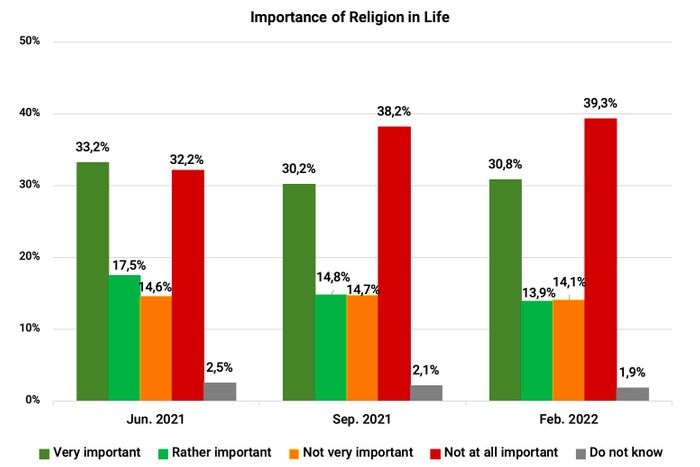

The religion survey went viral, collecting 50,000 samples and showing an undeniable secular shift across Iran: 47 percent of respondents claimed that in their lifetime they had gone from religious to nonreligious. This result spread rapidly inside Iran and sparked conversation among intellectuals, the media, students, and people all over the country. No academic organization had ever shown plausible proof of Iran’s secularity; people were excited and began holding discussion forums on social media and television, interpreting the outcome, scrutinizing the methodology, and suggesting new surveys. They made videos on WhatsApp and Telegram talking about secularism in Iran and the skewed perception the outside world had about their country. Because of GAMAAN’s growing reputation in Iran, the survey was discussed on all of the major television channels. Voice of America, Iran International, and Manoto TV, three of the most-watched channels in the country, all discussed it, and each time they published a video about it, the comments section blew up. Women scholars, activists, and thinkers appeared on television — one without a hijab even though she was inside Iran — reaffirming the results. Soon after, the researchers published a popular article on this shift in The Conversation, a respected journalistic outlet for academic experts.

Although mainstream western media outlets were still citing Gallup and Pew, GAMAAN’s success in Iran and abroad led to exciting new collaborations and support. The popular VPN Psiphon offered GAMAAN its platform as a way to reach more respondents. Knowledgeable insiders, such as economist Timur Kuran, the author of Private Truths, Public Lies who studies “preference falsification” (the very idea on which GAMAAN’s work is based), shared their religion survey. And in an inspiring moment for the researchers, Nobel Prize winner Shirin Ebadi reviewed questions for their next survey about capital punishment, the results of which were published by the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty.

Inevitably, the buzz reached the state media.

In August 2020, Mashregh News, a pro-regime outlet, posted a video refuting the results of the religion survey, and a major Iranian newspaper, Sobh-e-no, published a story titled “Another Pseudo-science” about GAMAAN, calling its sampling “mistaken.” For the undiscerning, GAMAAN was easy to refute; more prestigious pollsters like Gallup and Pew had reported different results. On January 9, 2022, Supreme Leader Khamenei explicitly spoke about the surveys, calling them false and unscientific. (Though he didn’t name GAMAAN’s poll, it was the only large-scale survey that showed mass secularization.) That same month, at the Second National Conference on Social Harm From the Perspective of Islam, Iran’s deputy interior minister expressed concern about protests linked to a desire for a secular government. Iran International and other news agencies cited GAMAAN’s data when reporting on the event. “This will be extremely alarming,” said the deputy interior minister, “if we find out that as a result of the incompetency of the government, people feel that the religious government is incapable of solving the country’s problems and that a secular government can be effective.”

The researchers saw this response as an indication of how important the surveys had become in Iranian discourse. The following month, they sent a new survey about various types of government to over 620,000 Iranians who connected to the unfiltered internet using Psiphon. They live-monitored the responses, targeting ads for less responsive provinces, and 17,000 people from inside Iran took the survey. The researchers were conservative about weighting the data; the 2019 Bloody November protests, a 2020 airplane shooting, and COVID had shifted popular opinion, with many Iranians fed up and rejecting the regime. During the pandemic, older people died in larger numbers, which (one can reasonably assume) might have shifted the makeup of the population toward the secular. With all of this in flux, GAMAAN still used pre-COVID weightings to give the religious segments of the population the maximum benefit of the doubt. And yet 67 percent of respondents said they didn’t consider religious law a good way to govern the country.

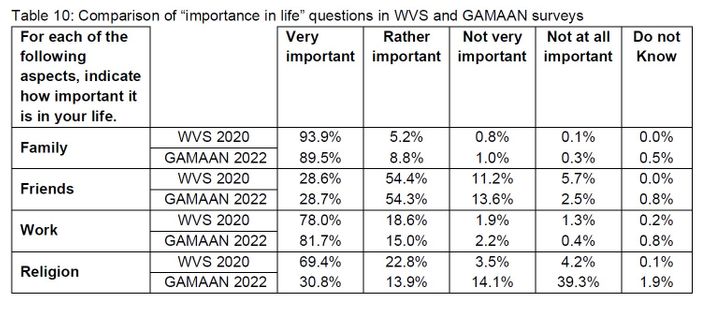

Given that the WVS is globally respected for gathering good data and that GAMAAN was only considering whether in-person surveyors were being lied to on certain questions, Maleki and Tamimi Arab in 2021 and 2022 decided to compare their anonymousresponses about the importance of friends, family, work, and religion to those of the face-to-face WVS. The responses closely matched across all questions except one: religion, the only question a rational person in a theocracy might not answer honestly if someone came to their door and asked.

This was an astounding result that has shocked precisely no one I’ve spoken to inside Iran. GAMAAN had simply fueled a fire that was already raging in the country.

After the release of the political-systems survey results in 2022, Clubhouse, a popular audio app on which Iranians often converse anonymously about politics in moderated rooms of thousands, exploded into heated conversation. Maleki was invited to explain the methodology and results and to speak in sessions with human-rights activists such as the recent political prisoner Majid Tavakoli. Iranians of all dialects, ages, and occupations debated the results. The range of voices was astounding: Tehrani academics, rural workers from the north and south, students, doctors, mothers. Some lasted hours — one marathon session ran for more than ten hours and included over 4,000 participants.

The Clubhouse conversations are mesmerizing to watch. For hours, people just squabble about methodology and the complexities of religion in Iran, sometimes slipping into Turkish, Azeri, or other dialects. Sometimes they joke or release their despair. A man with a sad voice like my father’s asked for everyone’s empathy: “Where were we 42 years ago? What did we expect then? Today in the hopelessness that these men have caused … I hope we can learn and understand what other people want and listen to each other.”

“Imagine thousands of people going online to talk about a survey,” says Tamimi Arab of the Clubhouse discussions. “It’s remarkable behavior. There is a thirst for this kind of information that was never available before.”

Soon after the 2020 religion survey, the Iranian Student Polling Agency, which is aligned with the regime, released a survey on religiosity with veiled and coded questions about God, blasphemy, and the like. It posted the results on Instagram, claiming that the country is hyperreligious. For example, it reported that 94.5 percent of people would dislike someone who insults the Quran. The comments were scathing. “Inshallah in the year 1400 the percentage of Muslims will be 110 percent,” someone wrote. Another joked, “It seems your survey was conducted during Friday prayers.” Another: “I’m telling you the people do not pray at all … people are fed up with Islam.” Several mentioned GAMAAN: “So you guys all of a sudden published this to prove GAMAAN wrong?”

People used the survey results to protest in a variety of ways in the languages of law, journalism, academia, and even popular culture. Young people began making TikTok videos discussing GAMAAN’s results or using them in comedy videos to make fun of the regime. It has even become a meme, a jokey way to claim something is absolutely true.

A comic video about the secularization of those raised under the Islamic regime, featuring a kid playing video game in a mosque.

Slowly, heftier scholarly verifications trickled in from abroad strengthening the people’s claim that GAMAAN’s data largely fits the context in ways previous surveys hadn’t. Since 2021, its research has been cited by think tanks in the U.K., the Netherlands, and Canada and in top peer-reviewed academic journals. Academics such as Roham Alvandi, an associate professor of international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science, tweeted support for GAMAAN. Abbas Milani, the director of Stanford University’s Iranian Studies Center, praised the GAMAAN surveys on Iran International, calling them scientific and meticulous and their results believable, adding that if you call an Iranian from abroad and ask their opinion about the president, the chances you’ll get the truth are “almost zero.”

Listening to Milani, a renowned scholar, Tamimi Arab shakes his head: “He said ‘almost zero.’ Right on Iranian TV!”

Next came a most satisfying outcome, one that would surprise every displaced person who has ever tried to navigate asylum law: The Dutch and U.K. governments cited GAMAAN’s data in their country reports and policy notes (which are used to assess asylum cases) to show that Iran has many Christian converts. These reports will undoubtedly mean that more apostates like my family will be believed by asylum officers.

Maleki and Tamimi Arab gave keynote lectures at prestigious venues like the European Association for Sociologists of Religion and the Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome. They won a grant from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences and were invited by senior demographers, scholars, and think tanks to share their work abroad, including at Stanford. “It was like opening Pandora’s box, shattering this image of a homogenous Islamic country,” says Tamimi Arab.

Despite this, many western sites and journals continued to defer to Gallup, clinging to its image of Iran. When processes are complex, Tamimi Arab and Maleki realized, people trust known experts and name brands. Only recently, a month after Amini’s death, did that image fall under wider scrutiny. The Guardian cited GAMAAN’s survey last month, linking to the results, andThe Wall Street Journal quoted it in a piece about the 2022 protests: “Iranian public-opinion surveys are often unreliable. But the number of people espousing staunch support for the Islamic Republic appears to be shrinking. According to a poll in March by GAMAAN, an independent research group based in the Netherlands, 18 percent of Iranians want to preserve the values and ideals of the Islamic Revolution.”

Listening to one of the packed Clubhouse conversations, Tamimi Arab recalled talking with a young woman from a wealthy, educated, and highly religious family, the kind of family that observes hijab around the house. She told him a story about the day she and her siblings and cousins were at home without their parents. One of the siblings said, out of the blue, “You know what? I don’t believe Islam anymore.” The next one said, “You too?” They had been pretending for such a long time, nervous about what the others might be thinking. “That’s why this survey is important and anonymity is important,” says Tamimi Arab. “It’s showing secular people that they’re many. Are they the majority? We don’t know. But we know this: Secular people in Iran aren’t some fringe group. They are numerous and everywhere.”

A strange thing happened to me a few years ago.

A young Tehrani writer reviewed one of my books in an American journal. She engaged with the arguments and narratives intelligently and thoughtfully. Then, out of nowhere, she mentioned an Instagram photo of me on holiday wearing a bikini. I was livid. I contacted the publication and asked if those sections could be removed. “Would you mention a man’s swimwear in a literary review?” I asked the editor. I thought, Would you do this to a white woman who wrote a book? I wasn’t inside the Iran conversation at the time. I was in the western literary conversation, so I read past all the subtext in her writing, her yearning for a kind of freedom I had enjoyed since childhood.

I dismissed that reviewer for a long time: She was sexist, probably religious, and had objectified me in a discussion about my work, I thought. This was about my writerly credibility. I couldn’t see, then, that to a secular woman in Iran, my bare stomach was political, obviously rooted in the same hybrid culture (Iranian-exile–cum–American) that gave birth to the book she was reviewing. Shouldn’t she mention my freedom if that freedom had given me my voice?

Recently, amid the protests in Iran, the memory of this long-ago interaction returned to me. How unfair I had been. I sent an email to the young writer asking if she was okay, if she could see the protests from her home, and we began a long conversation about hijab and secularism and choice.

She told me a story about her family. She had indeed grown up in a religious household; that’s why my bikini had been so shocking to her. Her mother wore a hijab in the house, and at 8 years old, she was put under hijab too. Every time she went to the homes of secular aunts and uncles, where nobody wore a hijab, her cousins teased her: “She’s like a little piece of candy, always wrapped up.” She was humiliated. Why did she have to live this way when her cousins got to be modern and fashionable? As the years went by, she found herself thinking more about the religion that kept her under the hijab. She wanted to cast it off. She worked up all her courage and spoke to her brother and discovered that he agreed with her, that his values too had become secular. “And as I was changing,” she continued, her voice excited now, “my mom was changing too.” Now she wears a more fashionable hijab and says to her daughter, “Maybe one day I’ll be like you.”

A few days ago, I saw a conversation among young people on TikTok, a battle between two young women, one seemingly religious, the other secular, both with American accents. The first woman said that people “spewing secular liberalism,” even those inside Iran, have “no political awareness.” The other countered that 70 percent of the population doesn’t want the Islamic Republic (which is GAMAAN’s number, though she didn’t say where she got it). Then an angry commenter said something I find important: Not having to live under a theocracy is a privilege. If you live in the West, even if you’re Muslim and have been marginalized in the West, you do not get to tell women in Iran how to live.

There are all kinds of privilege in this world — local minorities within national minorities, crossing with or underlying global minorities. My Iranian sisters are showing me that in a new way. We cannot apply the discourses of our small circles to other people’s lives. Iranians think we western onlookers are telling the wrong story about them, that we are wedded to our ideologies, our fixed menu of opinions. Maybe we have hoped for reform for so long we can’t see another way. Maybe we’re anti-imperialists and understand the horrors of past interference. Maybe we wish to protect our families from war. Maybe we haven’t yet delved into the intersectional nuances and complexities of modern Iran and think criticizing an Islamic government is the same as being Islamophobic. Or maybe we have fallen prey to the sampling problem: You can be a journalist for 20 years, interviewing hundreds of villagers and still never get a random sample, but you’ve seen enough to be entrenched in your view. You know because you know, because you’ve seen it hundreds of times. But that’s not enough. Ordinary people don’t know how to scrutinize data, and we believe the stories we already know. A Muslim Iran is the story we know.

I’m not saying GAMAAN’s survey shows the full complexity of the Iranian people. But if hundreds of thousands of Iranians are talking about it, if the supreme leader mentions it with fear, then we should dig deeper and try to understand the shortcomings of the methods we once believed in. We shouldn’t lump all Middle Eastern countries into one category or allow one group to speak for another. We should listen to those who are there.

Many once-religious communities are secularizing — my Oklahoma friends who wore “WWJD” bracelets are all secular now. Every faith has a spectrum of practice that is always changing. It’s lazy to rely on dichotomies to understand the world: We’re secular, they’re religious. It’s far more complex than that. And simpler, too, because everyone wants stability, safety, economic security, and the freedom to choose.

Iranians don’t want a piecemeal doling out of choices by an autocracy with its hands always on the freedom levers — a bit of leeway on scarves, a touch of magnanimity on property ownership or divorce or whatever else. Nobody wants statutes that can simply be overturned by future leadership. Every individual craves, at every moment, ownership over every personal choice. Who will give that to the Iranian people?

As GAMAAN was gathering data and stirring up debate in Iran, Tamimi Arab’s wife, Sara Emami, the visual artist, was drawing in her signature blue color. When women in Iran took to the streets after Amini’s death, she decided to try telling the story of modern Iran — the same one GAMAAN was telling — to western audiences in her own way. She created an image of a woman in blue, her hair blowing. It became a flag and a symbol for the 2022 support marches across the global West.

I believe Iran’s future will be decided by women — by academics, statisticians, artists, lawyers, doctors, women with and without the hijab who have had enough. It will be shaped by their talents and their stories. A few days ago, the young book reviewer in Tehran was walking past the university watching women protest. The wind blew off her shawl. But she saw a group of women without hijab, so she too dared to walk past the security forces bareheaded. Nothing happened. She sent me an Instagram video of three young women, heads uncovered, watching a woman in a hijab play her violin on the street. She sent me a giddy audio message: “The security forces just looked at me! And I felt free.”

Dina Nayeri is the author of the upcoming book Who Gets Believed? When the Truth Isn’t Enough.