Members of the Wagner Group look from a military vehicle with the sign “Brother” in Rostov-on-Don late on Saturday. (Photo by Roman Romokhov/AFP via Getty Images)

When Russian mercenary leader and oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin suddenly launched his march on Moscow on Friday, top US officials should not have been surprised; US and Ukrainian intelligence had warned that such a move was possible. In the aftermath of Prigozhin’s abortive rebellion, however, experts within and outside the US government were quick to express worry about the fate of the Russian nuclear arsenal should the regime of Russian President Vladimir Putin ever be overthrown.

Since mid-June, US and Ukrainian intelligence had observed movements of troops in Prigozhin’s Wagner Group that suggested he was planning an armed rebellion against the Russian defense leadership. These movements followed a Russian Defense Ministry order on June 10 that all mercenary groups, including Wagner’s estimated 25,000 troops, report to the central Russian military command starting July 1. Such a takeover would essentially have put an end to Prigozhin’s leadership of Wagner, the private military force that he founded.

On Friday, Prigozhin ordered his troops to take control of a major Russian military headquarters in southern Russia, then had them set off on a march on Moscow—but then, after consultation with Belarus President Aleksandr Lukashenko, called off the rebellion on Saturday.

In a story published Saturday, the Washington Post quoted an unnamed US official who contended that there was “high concern” in the run-up to Prigozhin’s short-lived rebellion about instability and the control of Russia’s nuclear arsenal among the intelligence community should Putin be ousted and a Russian “civil war” erupt.

If a mercenary group were able to seize power and gain control over some of Russian nuclear weapons, “the world [would]find itself in uncharted territory,” Alexander Vershbow, a former NATO deputy secretary general and US ambassador to Russia, told the Bulletin. “It is doubtful that the ousted Putin regime would be able to withhold access to nuclear codes for very long, if at all.”

Other experts shared this concern. “Any civil instability within a nuclear state raises fears over command and control of its nuclear weapons,” Mariana Budjeryn, a senior research associate with the Project on Managing the Atom at Harvard University, told the Bulletin.

It is not clear what might happen if a military group were to seize Russian tactical nuclear weapons.

The Wagner Group’s march on Moscow revived an old fear among US officials concerned that nuclear weapons in Russia might fall into the wrong hands. “The security of then-Soviet nuclear warheads was a major US concern during and immediately following the Soviet Union’s collapse,” Steven Pifer, a former US ambassador to Ukraine, said, noting that the US government devoted significant funding to bolster the security of those weapons. In 1991, the US Congress passed the Soviet Nuclear Cooperative Threat Reduction Act (also known as the Nunn-Lugar Act, after the name of the two senators who sponsored it), which provided resources to secure and dismantle weapons of mass destruction and their associated infrastructure in former Soviet republics that had become independent countries.

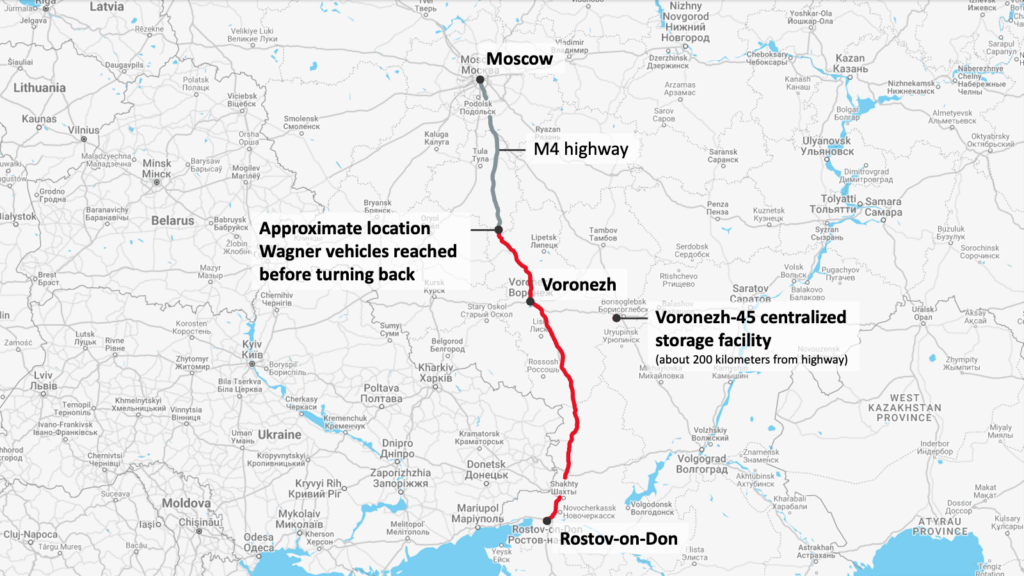

On Saturday, some news reports suggested that Wagner troops were about to seize one such nuclear weapon storage site, although none of these reports could be independently verified. “At least one facility that could house Russian weapons was on the mutineers’ path to Moscow: Voronezh-45 central nuclear storage facility,” said Budjeryn. But it is unknown whether the facility currently hosts nuclear weapons, she added. (The Voronezh-45 facility is one of the 12 national-level centralized storage facilities tasked with hosting Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons, such as gravity bombs and warheads for air- and ground-launched missiles.)

In Russia, all nuclear weapons stored separately from their delivery systems are under the control of the Defense Ministry’s 12th Main Directorate (12th GUMO), including those at the Voronezh-45 facility. An attacking force, especially a group as heavily armed as the Wagner Group, might be able to take possession of some warheads at such a facility. But that would not mean the attackers could quickly arm or use those warheads, all experts agreed.

For one thing, a group seizing power would not necessarily gain physical control of complete nuclear weapons. “Most, if not all, stored Russian tactical nuclear warheads are not fully assembled,” Pifer said. Matej Rafael Risko, a research fellow at the Institute of International Studies in Prague, commented on Twitter that warheads for the OTR-21 Tochka, a Soviet-era mobile short-range ballistic missile launch system now being replaced by the somewhat longer-range Iskander missile system, “are stored in an incomplete assembly, the so-called readiness stage.”

“This means that the neutron tubes are not installed, the MED electro-detonators are not connected, and the electrical system is not connected to power sources,” Risko added.

Even if rebels gained control of all the physical components of a nuclear weapon and assembled it, they could not necessarily use it. For a nuclear warhead to be used, it would have to go through a complex set of deployment procedures; among other things, a rogue group would need to mate a warhead with the right delivery system. In a blog post, Pavel Podvig, director of the Russian Nuclear Forces Project, explained that Russian nuclear weapons are stored separately from their delivery vehicles. He estimates that Russia has not only 12 large national-level storage sites but also about 35 base-level storage facilities. In some cases, a base-level storage facility can contain weapons that are assigned to delivery systems collocated at that same base. But in any case, mating a nuclear warhead to its delivery system is a task of extreme complexity, which an invading military group would most likely not be able to accomplish without the active—or forced—cooperation of 12 GUMO personnel.

Russian non-strategic nuclear warheads are locked via permissive action links (also known as “PALs”) that require codes to unlock. (Russian strategic nuclear weapons use other ways to prevent unauthorized and unintended use.) PAL codes were developed in the 1960s to guard against unauthorized use of a non-strategic nuclear weapon. “But PAL locks are like safe locks—with enough effort they could be broken,” Budjeryn explains. Moreover, experts are uncertain whether PAL codes are released by the central command or kept on base, as in the United States—a possibly highly consequential detail. “It would be very poor security indeed if PALs were just kept on base,” Budjeryn told me. “At least part of the code must be with the national command authority that would release them when they authorize the use.”

So, what interest would a military group like Wagner have in seizing a tactical nuclear weapon, if it couldn’t be used? “The mutineers could have used the captured weapons as political leverage in the short term,” said Budjeryn. Then, she added, “with sufficient expertise and time, PALs could potentially be hacked.”

This weekend’s failed coup seems not only to have revealed cracks in Putin’s grip on power but also the limits of safety and security arrangements for the Russian nuclear arsenal. Should a military coup ever succeed in Russia, coup leaders would likely gain effective control of nuclear weapons, which could pose a threat to strategic stability, prompting immediate international efforts to restore it. “Other nuclear powers would need to warn the new leaders of the severe consequences of using or threatening to use nuclear weapons … press them to establish effective security controls over Russian weapons and renounce nuclear coercion,” the former NATO official Vershbow said.

As of now, Wagner’s military rebellion fell short, and Prigozhin—who experts say has not publicly expressed interest in access to nuclear weapons—is in exile in Belarus. Still, Vershbow said, “I don’t think Russia has seen the last of Yevgeny Prigozhin.