|

إستماع

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Two weeks ago, after yet another boy from Lod was murdered, I finally decided to buy the book “Children of the Ghetto: My Name is Adam” by the Lebanese author Elias Khoury.

I wanted to see if there was any connection between the character of Adam, who was born in Lod in 1948, and the wave of murders in Lod, and in the Arab community more generally.

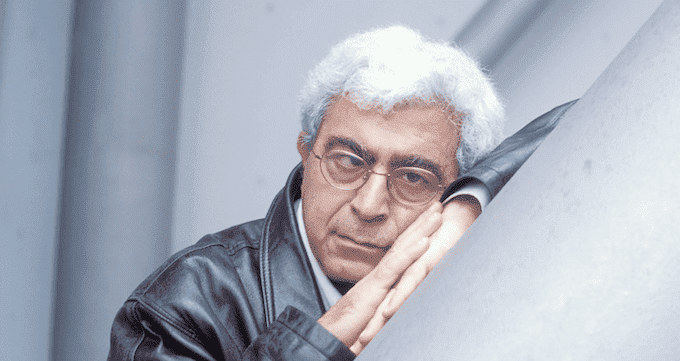

Unfortunately, while I was reading the book, Adam the character committed suicide, another resident of Lod was murdered and Elias Khoury passed away.

The first time I encountered Elias Khoury was also the first time I decided to read a book. I was sleeping over at the home of the first producer of my performances, who was from the north. I had met him when I started performing and becoming known.

During one of our long nighttime conversations, I pointed to the dozens of shelves of books decorating his home and admitted that there were no books in our home. I didn’t come from a home where people read (only in the final decade of my father’s life, after he got in a traffic accident and became wheelchair-bound, did he decide to learn to read and write and fill the house with books about the Islamic faith).

I defended myself to my intellectual producer as if I had been accused of something. “Leave me alone,” I said. “I get my wisdom from the streets. And if we’re talking about culture, then I prefer watching movies.”

My producer responded that it’s irrational for me to write stories without reading stories. Then he quickly pulled out two books, as if he had prepared them in advance and laid a trap for me. The first book he gave me was a short one called “To Be an Arab in Israel,” published in 1975. It was written by Fouzi El-Asmar, who grew up in Lod’s Harakevet neighborhood, known today as “the Arab ghetto.” As a boy, El-Asmar witnessed the capture of his city by the Israel Defense Forces in 1948.

The second book was Khoury’s “Gate of the Sun: Bab al-Shams” (2002). Just holding it gave me a panic attack. Not only was it a thick book (544 pages), but it was also in Arabic. Not that I didn’t read Arabic; I actually read and wrote it well. But my eyes were used to Hebrew, because the subtitles at movie theaters were in Hebrew.

But I decided to impress my producer and read both books. I don’t remember which I read first. But in “Gate of the Sun,” for the first time, I lost myself in stories about the Nakba.

Before then, the Nakba was a kind of rainfall poured down on me by the people around me; either spontaneously or at events commemorating the Nakba, someone from that generation would get up and pour out their stories. But the first time I stripped off my clothes and dived deep into the Nakba was while reading “Gate of the Sun.” I truly drowned in the characters’ blood, in their tears, in my own tears. And I sometimes I couldn’t tell which of us was crying.

One of the things I remember best about “Gate of the Sun” is the flies – both the number of flies and the size of each fly that sprung directly from each death. And that reminded me of the flies I drove away with my hands every time I found a body (that’s a story for another day).

Something about Khoury’s description of the flies during the massacre that occurred during 1948’s accursed Operation Dani reminded me of the flies on the windshields of bullet-ridden vehicles during underworld killings in Lod. Something about those flies says that they belong in this accursed place more than the Ottomans, the British, the Palestinians and the Jews all together. We’ll continue to replace each other, but the flies will remain the landlords of this place.

I have never understood why the fly isn’t considered an angel of death. It’s black, frightening, winged and is the first to appear at the scene of a death, as if it had been there all the time but hadn’t managed to get away before we arrived.

The second time I had an encounter with Khoury was on January 13, 2013, when Israel decided to annex territory near the West Bank settlement of Ma’aleh Adumim and young Palestinians decided to set up a tent city as an act of resistance. They called this village Bab al-Shams (“gate of the sun”) after Khoury’s book.

As a sign of solidarity with this Palestinian action, I wrote a song that had the same name. In it, I brought the book’s characters to life and made them dance with the founders of the new village until it was impossible to distinguish between Khoury’s characters and those of the young Palestinians, just like Khoury made it impossible to distinguish our tears from those of his characters.

I got an email from Khoury about the song, which somehow reached him. He really liked the idea, gave me half a sentence of praise and then voiced gentle criticism of my diction. I apparently elided a vowel here and there. I replied “thank you,” as excited as a teenager who had met his idol, and I joked that if they start arresting people for bad diction, they should prepare a giant island for all the rappers. And of course, before I hit “send,” I asked a poet friend to proofread my email.

The third encounter took place in Berlin. My film “Junction 48” was ready, and I and my friend, director Udi Aloni, decided to hold a private screening for Khoury, since both of us considered him our idol. Khoury watched the film, Udi watched Khoury watch the film, and I waited impatiently to meet up again with my first event producer so I could close the circle and say, “Bro, I managed to get my literary side and my cinematic side into the same room.”

In retrospect, I realized the Khoury was in the midst of writing his next novel, “Children of the Ghetto,” which is set in Lod. So every time a scene went by in “Junction 48,” he would look at me as if I were a version of the Shazam app, but for identifying locations instead of music, and say, “this is the Al-Khadr church, right?” “This is Khan el-Hilu?” Khoury had never been to Lod, yet he was able to identify every millimeter of it just from the research he did and the stories he had heard.

To our delight, he liked the film, and he had no comments about the diction. After all, it’s our world now, that of the third generation of the Nakba, the generation that has moved away from Khoury’s Adam a little in terms of the type of death, but not in terms of the fact of death. After all, none of my friends today calls me to say “did you hear about Operation Dani?” We’re more like, “Did you hear about the [underworld]assassination yesterday?”

The way Khoury and I spoke about Lod, one from afar, one from up close – and I don’t know which of us was from afar and which from up close – was both sad and moving, emotionally and creatively uplifting. That time there was no consciousness, not of literature, song nor the camera. That time will remain between us, with no flies on the wall.

(Recommendation for anyone who reads Hebrew: One of Khoury’s conditions upon publishing “Children of the Ghetto: My Name is Adam” was that Hebrew be the first language it was translated into, so that Israeli Jewish readers could be exposed to our pain. Yehouda Shenhav’s translation is as moving as if Khoury had written the book in Hebrew. Run out and buy it. Don’t wait until it, too, is on liquidation sale.)