With ample Russian and Iranian help, regime forces have cut the rebels’ main lifeline in the north, and they will likely steer their relentless steamroller to the west unless outside powers take action.

On February 2, the Syrian army and its allies succeeded in cutting the northern road between Aleppo city and Turkey, known as the Azaz corridor. Although the battle was a local affair involving a relatively small number of fighters, it may prove to be a turning point in the war. In addition to threatening the rebel presence in Aleppo province, the development could put the entire Turkey-Syria border under the control of pro-Assad forces within a matter of months, or spur Kurdish forces there to choose coexistence with Assad.

CUTTING THE NORTHERN CORRIDOR

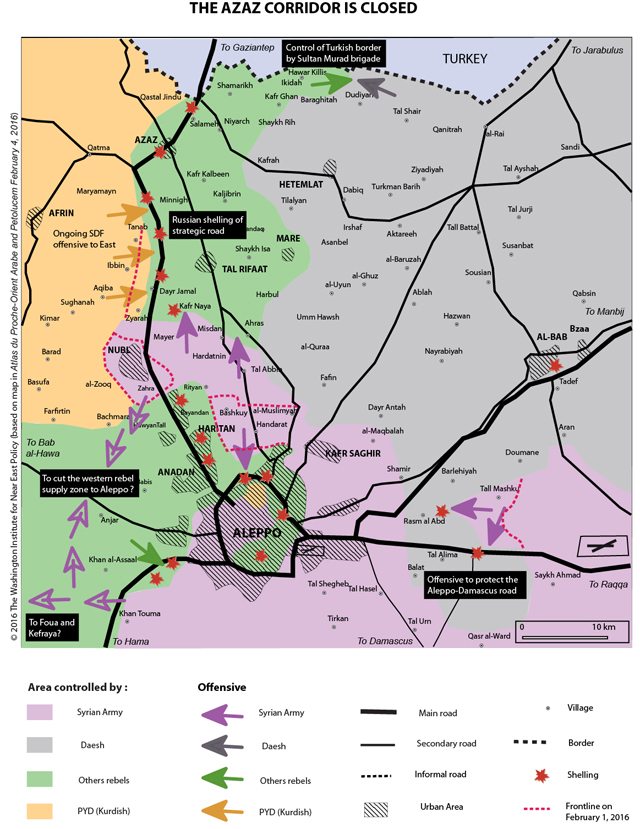

The offensive against the corridor was launched from Bashkuy (on the northern outskirts of Aleppo) and from the pro-regime Shiite enclave in the villages of Nubl and Zahra. Hezbollah and two other Iranian-supported Shiite militias (the Iraqi brigade al-Badr and the enclave’s local “National Defense” militia) are the main ground units participating to the battle, pitted against rebel forces led by al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra, which had previously sent hundreds of reinforcements from the Idlib area.

(For maps illustrating the military maneuvers and locations discussed in this PolicyWatch, go to http://washin.st/1miJtGe)

For Shiite fighters, the purpose of the battle is highly symbolic: to defend their fellow Shiites against Sunni Islamists who want to expel them. The small Nubl-Zahra enclave has resisted rebel assaults for three years, with the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) protecting its western flank and allowing food deliveries to enter. In exchange, the Syrian army has protected Aleppo’s Kurdish neighborhood of Sheikh Maqsoud against rebel attacks. Passive cooperation between the PYD and the Syrian army is now becoming active as both forces are on the offensive against rebels in the Azaz corridor.

A February 2015 attempt to join the Nubl-Zahra enclave with the government zone failed dramatically due to lack of preparation and insufficient forces. Afterward, a heavy rebel counteroffensive took Idlib, then threatened Aleppo and even Latakia. Bashar al-Assad was obliged to ask for Russian intervention without any conditions. In contrast, the latest offensive was preceded by weeks of heavy aerial bombardment against rebel defenses, particularly at the Bab al-Salam border post with Turkey, through which the rebels receive many of their supplies.

The opposition-controlled corridor between Aleppo and Turkey is only five to fifteen kilometers wide, wedged between Islamic State (IS) forces to the east and the Kurdish canton of Afrin to the west. The main rebel groups in this area are Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zinki, and the Sultan Murad brigade (a Turkmen group very close to Turkey). These groups are formally members of the rebel umbrella organization Jaish al-Fatah, which is supported by Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Since their victorious campaign of spring 2015, however, significant internal divisions have emerged. Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra have recently fought each other, while Nour al-Zinki has withdrawn from the outskirts of Aleppo, and Sultan Murad is only fighting IS forces, not Assad.

The Azaz corridor grew particularly weak after the Democratic Forces of Syria (DFS) — an alliance of Kurdish and Arab forces under the PYD umbrella — gained the upper hand against the rebels and began to advance westward in recent weeks, approaching the Aleppo-Azaz road. The DFS has benefitted from Russian shelling against rebel lines, as well as direct Russian weapons deliveries. On February 4, the group announced the capture of two villages north of the Nubl-Zahra enclave, Ziyarah and al-Kharba. In light of this situation, the Syrian army’s latest victory would seem to benefit the Kurds, who can advance in the northern part of Azaz corridor while regime and allied forces content themselves with solidifying their position around Aleppo instead of heading to Azaz.

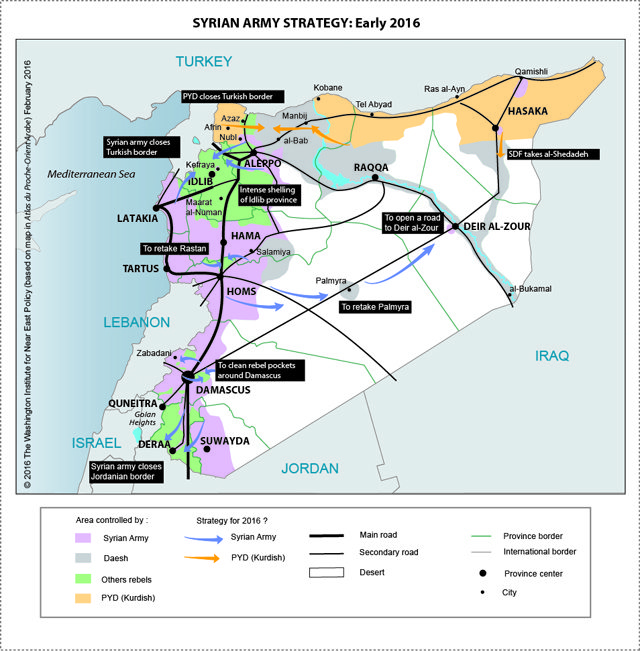

CLOSING THE WESTERN BORDER

Now that the northern road is cut, the next target is likely the road from Aleppo to the rebel-controlled western border crossing of Bab al-Hawa. In parallel with the Azaz offensive, Hezbollah launched attacks in the northern suburbs of Aleppo to cut the road called “Castello,” by which the eastern rebel neighborhoods are supplied. This offensive has been less brutal than the one in the north because the terrain is more difficult to conquer: the high density of residential buildings prevents tanks from progressing. The regime and its allies will not try to retake this area quickly, since the risk of heavy losses from urban warfare is too great. The best solution is to surround it and wait, which will allow time for tens of thousands of civilians who remain in eastern Aleppo to flee. Many fighters are fleeing as well, perhaps because they fear they will not be able to withdraw once the area is fully besieged, as happened in Homs in spring 2014.

Meanwhile, Syrian and Russian efforts will likely focus on the countryside west of Aleppo. From Zahra, it is now possible to attack the rebels northwest of Aleppo and support similar actions from the southwest, where the army has progressed a great deal since October. Again, Assad’s forces are unlikely to tackle dense urban areas, instead moving in the open field and cutting rebel lines of communication. In the coming months, the army and its allies will probably aim to seize a sizable section of the western border between Bab al-Hawa and Jabal Turkmen in northern Latakia province.

At the same time, the PYD might attack the ninety-kilometer border area between Azaz and Jarabulus in the north, currently held by IS. This would be in keeping with the group’s strategy of linking the Kurdish enclaves of Afrin and Kobane. Unlike the United States, Russia does not want to antagonize the Kurds by prohibiting their deeply held goal of territorial unification. Moreover, Vladimir Putin wants to put pressure on Turkey’s entire frontier with Syria: it is one of the main regional goals of the Russian intervention. If the PYD and pro-Assad forces succeed in their separate offensives, the whole border will be under their control, with no window into Turkey for anti-Assad forces, be they rebels or IS.

LAUNCH A COUNTEROFFENSIVE OR OPEN A NEW FRONT?

Moscow’s strategy since September has been shaped by three goals. The first is to protect the coastal Alawite area where Russia has installed its logistics bases. The second is to strengthen Assad, pushing the rebels far from the large cities of Homs, Hama, Latakia, Aleppo, and Damascus. The third is to cut the rebels’ foreign supply lines.

The first two objectives have largely been met: there have been no attacks on Latakia or Tartus that could interfere with the Russian bases there, and no large city has fallen to the rebels. To the contrary, the rebels evacuated the Homs neighborhood of al-Waar in December because they were desperate, not seeing any help coming.

Now that the Azaz road has been cut, the third goal is halfway reached. Russia and its allies seem to have the means to meet their ambitions, with Assad’s manpower weakness offset by complete air superiority and Shiite militia reinforcements.

Yet Turkey and Saudi Arabia may not remain passive in the face of major Russian-Iranian progress in Syria. For example, they could set up a new rebel umbrella group similar to Jaish al-Fatah, and/or send antiaircraft missiles to certain brigades. Another option is to open a new front in northern Lebanon, where local Salafist groups and thousands of desperate Syrian refugees could be engaged in the fight. Such a move would directly threaten Assad’s Alawite heartland in Tartus and Homs, as well as the main road to Damascus. Regime forces would be outflanked, and Hezbollah’s lines of communication, reinforcement, and supply between Lebanon and Syria could be cut off. The question is, do Riyadh and Ankara have the means and willingness to conduct such a bold, dangerous action?

Whatever the case, without that or another black-swan development, it is difficult to see how the rebels can resist the Russian-Syrian-Iranian steamroller. The latest successes in Aleppo place Putin at the center of the Syrian chessboard, contrary to forecasts that Russian intervention would make little difference or trap Moscow in another quagmire.

******************************

Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.