|

إستماع

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The first Sami Michael book I read was “A Storm among the Palm Trees,” as part of a master’s thesis at CUNY in New York on “The Attitude of Arabs and Jews to the Farhud,” the pogrom against the Jews of Bagdad in June 1941. I found many references to this event in Arabic by Iraqi historians and politicians. Still, I could not find any reference by Iraqi Jews to this terrible pogrom. Sami Michael’s book, “A Storm among the Palm Trees,” expressed his longing for the Iraqi homeland, for his rowing as a young man on the Tigris River when the future of Iraq, including of its Jews, looked so promising. He gave pronunciation to the Jewish pain and disillusionment in the Iraqi homeland that betrayed its Jewish citizens who dared take an active role in the development and construction of an independent Iraq. Thus, Iraqi Jews, including those who left Iraq in 1951, have hidden and suppressed the traumatic event for many years. However, later on, mostly in the last decades, many articles have been written about the Farhud, a milestone in the history of the Babylonian community that led to mass immigration to Israel (and elsewhere) a decade later.

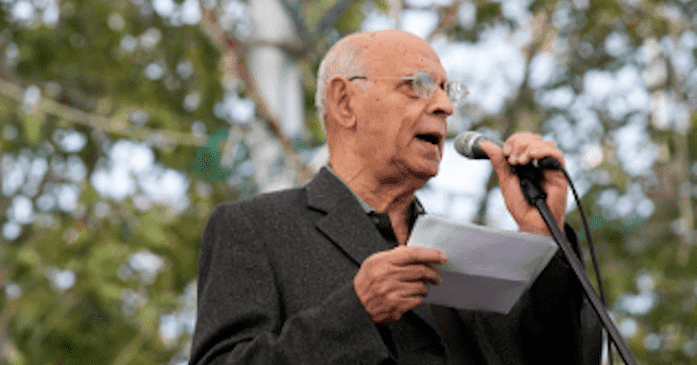

“A Prince and a Revolutionary” is how literary critic Prof. Yigal Schwartz entitled the book he edited for Sami Michael’s literary and scholarly work. This book compiles articles based on a conference held at Northwestern University in Chicago a year earlier. Michael’s work gained recognition and appreciation in Israel and was translated into many languages. Indeed, his very description as “A Prince and a Revolutionary” encapsulates Michael’s personality and long-standing writing more than anything else. He was a literary prince who left his mark on Hebrew literature and a socially conscious revolutionary throughout his life and work.

Born in Baghdad in 1926 as Kamel Salah Menashe, he grew up in a wealthy modern Jewish family. He was educated at the Shamash Jewish School, which emphasized the study of English and French, and modern Arabic literature, which flourished in Baghdad in those years. His fine Hebrew prose writing later expressed these foundations. At the age of 15, after the pro-Nazi Rashid Ali al-Kilani revolt and the ensuing pogrom against the Jews of Baghdad in June 1941 (known as the Farhud), he joined the Iraqi Communist Party, like many young Iraqi middle-class Jews. They viewed communism as a secular and enlightened solution to the mosaic of religions and ethnic groups in Iraq. They also considered it as a remedy against the antisemitism that surged in Iraq, especially in light of the discussions on the UN partition resolution towards the establishment of a Jewish state. He was active in the communist underground, which was persecuted by the regime. He published articles in the communist press, and, like many communist Jews, he did not support the Zionist national movement (or any other national movement that would have interfered with his Iraqi identity).

After an arrest warrant was issued against him, he fled to Iran and changed his name. To forestall potential extradition to Iraq, he immigrated to Israel. He settled in the Jewish-Arab mixed city of Haifa and, with the instigation of his friend, the Haifa Christian-Arab writer and intellectual Emil Habibi, began writing in the communist and Arabic language publications: al-Ittihad and al-Jadeed. He left the party in 1955 due to disillusionment with Stalin’s crimes against humanity in the Soviet Union. He completed his academic education and started writing prose in Hebrew while working as a hydrologist in the Ministry of Agriculture. His writing deals with and identifies with the Jewish-Israeli experience and the universal values ingrained in him since his youth in Baghdad.

Michael’s Hebrew language writings are characterized by a realistic style and relate to the social environment of his characters; his first books relate to the immigrant society in which he found himself, to life in the Israeli transit camps, but also life in the mixed city of Haifa and to his Arab neighbors. He also wrote books for children and teenagers, as well as young adults’ books about the Israeli experience, such as “Refuge,” a story about a group of Jewish and Arab liberal youngsters supervised by the government during the Yom Kippur War of 1973, and even some non-fiction books “Tribes of Israel” (1984) and “The Israeli Experience.” (2001) He also translated into Hebrew Arabic literary works.

Being a socially conscious “revolutionary” runs through many of his books, as well as his continuous stride for peace between Jews and Arabs. The immigrants, the residents of the Israeli transit camps facing poverty and hardships, the conflict with those Israelis who saw themselves as the founding elite of the country, expressions of compassion and affection for the weak and disadvantaged. His outstanding book, “Victoria,” which describes the life of one Jewish woman and her family from childhood in Bagdad to old age in Israel, highlights the class gap and the exploitation of the weak, particularly women within the Jewish community in Baghdad. This popular book may have embarrassed some of his readers from the old Baghdadi community, but it emphasizes authenticity.

In the book “A’ida” (2008), Michael surprised his readers with a novel set in Iraq 40 years after he left the country during the Saddam Hussein era. He describes an Iraqi Jew who decided to stay alone in Iraq after sending his family to Israel and who flourishes financially and succeeds in Iraq’s regime of corruption and decadence due to his friendships and dependence on the corrupt government. Yet this man shows human compassion for a suffering Kurdish woman knocking on his door.

In his inspiring book “Diamonds from the Wilderness” (2015), Michael returns to Baghdad in the 1930s in a sweeping love story between two young Jews, a “privileged” young man of an established class and a poor young woman who works as a maid in his home. The love story unfolds against the backdrop of a bustling and magical city. Here, Michael also expresses his uniqueness as a revolutionary prince, his love of all human beings, and his courage to confront injustice. In that spirit, since 2001, he has served as the president of ACRI – The Association of Civil Rights in Israel.

Sami Michael was neither born in Israel nor grew up there. He was not educated there as a child or teenager. Furthermore, he did not define himself as a Zionist in the straight-forward sense of the term until the mid-50s. Still, he embodies in his life and in his literary work the humanistic Zionist idea on which the Jewish state was founded and prospered until recently. In this sense (and in other ways), he was a kind of an elder brother to many of us. His sober yet creative voice will be missed in the coming days and years.

[1] Yigal Schwartz, Ed. A Prince and a Revolutionary – Reading Sami Michael’s Prose (Hebrew) Gama Publishers 2016