Despite their desire for greater independence, Syria’s Kurds have shown a willingness to broker agreements with the Assad regime in order to secure their near-term economic interests, and they may soon do the same with Iran.

Note: Click on maps for high-resolution versions.

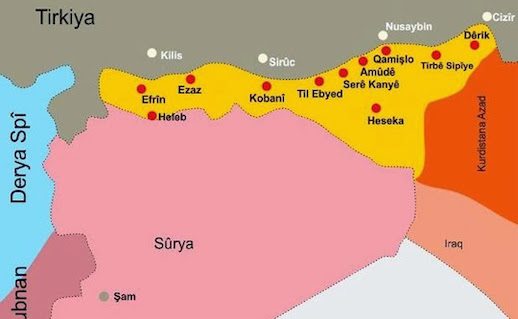

In February, the Syrian army met up with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces south of Manbij, a development that Kurdish authorities have characterized as a means of linking the northwestern canton of Afrin with the rest of their territorial bloc along the Syria-Turkey border. The Democratic Union Party (PYD), the Kurdish militia that dominates the SDF, would have preferred to control this link with its own troops rather than relying on the Assad regime, but recent Turkish operations blocked its westward march. Even so, the situation gives the Syrian Kurds of Rojava another means of preventing other actors from boxing them in politically or economically, at least for now.

ROJAVA STILL BELONGS TO SYRIA’S ECONOMIC SPACE

Although the latest developments will facilitate the circulation of goods between Afrin and the rest of Rojava, any such movement is still subject to the regime’s goodwill. Fortunately for the PYD, Bashar al-Assad has a mutual interest in expanding economic relations with the Kurds. Western Syria needs the cotton, wheat, and oil produced in Rojava’s easternmost Jazira canton, while the Kurds need to export their raw materials and import manufactured goods. Thanks to this new overland connection, Syrian Kurds will be less dependent on Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) for their supplies; the northeastern passage to Peshkhabur, Iraq, is no longer the only international trade route open to them.

Of course, Kurdish wartime trade relations with western Syria were ongoing even before February’s Afrin linkup. Goods continued to circulate between Rojava and regime territory, with taxes levied by the Syrian army as well as various Assad-allied and rebel militias. For example, trucks transporting Jazira’s grain harvest to government areas had to pay a commission to Islamic State forces when passing through their territory. And in recent months, whenever Afrin was supplied with fuel from refineries in the Rmelan region east of Qamishli, Turkish-backed rebels in between the two areas took as much as half the cargo in “tolls.” Since February, however, Kurds have been able to send fuel through the Syrian army corridor between Manbij and Afrin via Aleppo. Assad’s forces have kept their own tolls relatively low to incentivize the use of regime-controlled roads. Facilitating trade with Rojava helps Assad politically as well, keeping the Kurds under his economic influence while also benefiting key associates and family members such as Rami Makhlouf, owner of FlyDamas, the principal airline serving Qamishli.

QAMISHLI AIRPORT IS INDISPENSABLE

Despite being located deep within Rojava, Qamishli Airport is still under the Syrian army’s control. The PYD never tried to take it because it is an indispensable means of communication for Rojava. The two daily flights to Damascus are full of essential cargo, as are the two weekly flights to Beirut and the weekly flight to Kuwait. It also the easiest way for local civilians to travel abroad. The nearest international airport is Erbil, a full day’s drive away. Crossing the Tigris River to Peshkhabur is a painstaking process because civilians cannot use the barge, which is reserved for cargo trucks. Customs formalities take up ample time as well.

Prior to February, Qamishli Airport was also the only way for Kurdish civilians to reach the western regime zone. Throughout the war, thousands of students who attend universities in Aleppo, Damascus, Homs, and Latakia have been concerned about losing the ability to travel back to their homes back in Rojava. Access to Damascus is essential for medical reasons as well — Rojava hospitals are poorly equipped, and most of their medicines come from the regime zone. Public salaries and pensions from Damascus have also arrived by plane. In short, Kurdish authorities do not yet have the means to replace the Syrian state in many sectors.

ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE: IDEOLOGY VS. PRAGMATISM

The PYD takeover of Hasaka province in 2012, as well as the breakdown of territorial continuity with the regime zone when rebels seized the Euphrates Valley, completely disorganized the local economy. Previously, Hasaka had been assigned the role of producing raw materials, particularly oil, cereals, and cotton. For example, its cereal output typically constituted around half of the country’s total production, helping to ensure Syria’s food independence. Hasaka also produced 80 percent of the country’s cotton before the war. This “white gold” fed Syria’s powerful textile industry and was exported for great profit. Farmers had to take part in very strict regime-mandated production plans that excluded other crops. Public offices for wheat and cotton supplied them with seeds and bought their whole crop at prices fixed by the state. Similarly, local agricultural administrations supplied fertilizers from the huge chemical plant in Homs at low cost.

As a result of these policies, Hasaka came to resemble an internal colony forced to feed western Syria with raw materials. The creation of local industrial enterprises was long forbidden, and while the state opened two spinning mills there, most of the country’s cotton was processed in Aleppo and the coastal region. Moreover, the province had no textile sector to speak of, while its agro-food industry was limited to a few artisanal dairies and flour mills for local needs. Although it produced one-third of Syria’s oil, it had no refineries or plastics industry. The Rmelan thermal power plant covered only strategic needs related to oil extraction; most other electricity came from the Baath, Tishrin, and Thawra dams on the Euphrates. By enforcing such economic dependency, the regime hoped to avoid any secessionist attempts by the Kurds — in striking contrast to the Alawite coastal region, which Bashar’s father endowed with all the infrastructure needed to establish an independent sectarian bunker if the regime ever lost power in Damascus.

Today, the PYD advocates a self-sufficient economy to liberate itself from unequal relations with Damascus. It also rejects the capitalist system and seeks to promote the philosophy of Abdullah Ocalan, leader of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), who has long advocated more Marxist-leaning policies. At the moment, however, these ideas can only be implemented on a small scale in Rojava, so Kurdish authorities likely feel compelled to open up their territory in order export their raw materials and trade for manufactured products. In this context, opening a second commercial route to Iraq would strongly reinforce Rojava’s independence, and much more rapidly than the slow and uncertain construction of a self-sufficient economy.

A WESTWARD ROUTE FOR IRAN?

A new land route between Hasaka and Kirkuk could allow Rojava to break its dependence on the Peshkhabur border crossing, which remains under full control by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the leading faction in Iraq’s KRG. This route would likely pass south of the Yazidi Mountains before reaching Tal Afar and then Kirkuk through the Tigris Valley, now controlled by the Iraqi army and its associated Shiite militias. Kirkuk is dominated by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), a KRG faction that is close to Iran and Baghdad, unlike the KDP.

To be sure, the feasibility of opening this route is not yet assured because the Islamic State is still present south of Sinjar, while the KDP and PKK are currently clashing for control over Sinjar itself. Moreover, KDP president Masoud Barzani and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan both oppose any strategic axis that opens Rojava up to the outside world and reinforces its geopolitical importance for Iran. Yet if current trends continue, a corridor could be established between Hasaka and Kirkuk, essentially linking Syria’s Kurds to Iran via Sulaymaniyah. Theoretically, Rojava could then become an Iranian transit route between Iraq, western Syria, and even the Mediterranean coast, at least once U.S. forces leave eastern Syria. Although this is not the shortest potential westward route for Iran, it would have the advantage of circumventing Islamic State strongholds along the Syria-Iraq border, where the terrorists are likely to take refuge after being expelled from Raqqa and Mosul. Accordingly, if the United States and its allies hope to prevent Tehran from establishing such a corridor, they will need to reinforce their own influence in Syrian Kurdish areas.

Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.