Like all good policy decisions, the deal emerged from the enlightened self-interest of the key parties, but the stakes are not as high as with Israel’s previous two Arab peace treaties.

Question: What is both bigger and smaller than it seems at first glance?

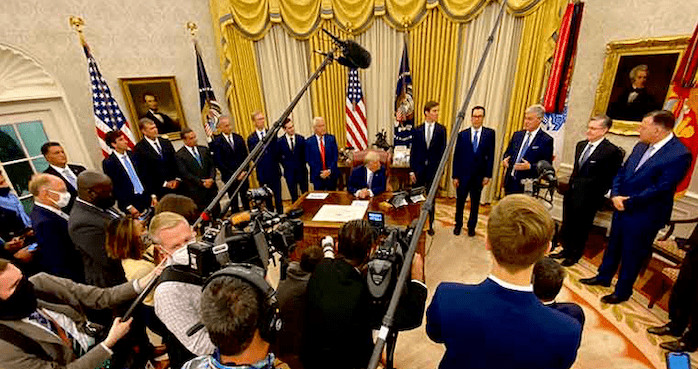

Answer: Last week’s announcement of full normal relations between the United Arab Emirates and Israel, arranged through the good offices of the United States.

I am a huge fan of the UAE-Israel deal, which will open opportunities for cooperation, partnership and synergy between the most dynamic, forward-looking economies in the Middle East. I am not a huge fan of the mischaracterizations that have filled the airwaves and op-ed pages in the days since the news broke. A reality check on what the UAE-Israel deal really means—and what it doesn’t mean—is in order.

On one level, I believe this deal is “bigger” than many are crediting. It marks a psychological big-bang in Arab-Israeli relations, breaking 72 years of refusal by the nineteen Arab states that don’t have a border with Israel to come to terms with the Jewish state. From Morocco to Oman, those states have maintained varying degrees of distance allegedly out of fealty to the Palestinian issue. In reality, many of them were able to maintain their aloofness precisely because Israel provided many of the economic, agricultural, hydrological, security and intelligence benefits of bilateral relations through clandestine channels, without the Arab side having to pay in the coin of formal, diplomatic relations.

Now that the Emirates has blazed a new trail, pressure will be exerted in two directions. First, there will be pressure on the eighteen Arab holdouts to explain precisely what about their commitment to the Palestinian issue is restraining them from enjoying the added benefits of ties with Israel that the Emirates evidently believe will come with full, normal relations. And second, there will be pressure on Israel to deny their Arab paramours the advantages of secret trysts when the precedent of legitimizing their relationship has been set.

The jury is still out on another aspect of the UAE-Israel deal that could make it even “bigger” than it seems—the fact that the agreement injects a measure of “linkage” into Arab-Israeli peacemaking. Linkage is a concept against which Israeli leaders have been fighting since the modern “peace process” was born nearly fifty years ago. Indeed, one of the great ironies of the Emirates deal is that Benjamin Netanyahu—heir to revisionist firebrands Zeev Jabotinsky and Menachem Begin, architect of the idea of Israel’s unilateral annexation of territory occupied in the June 1967 war—is the Israeli leader responsible for reinserting “linkage” into the peace process equation.

Ever since the first Egypt-Israel disengagement agreement after the October 1973 war, Israeli leaders have wanted to separate their emerging interstate relationships with Arab capitals from their inter-communal conflict with Palestinians. Under the Labor Party, Golda Meir and then Yitzhak Rabin leveraged their grudging agreement to cede territory to Egypt and Syria into US commitments not to deal with the Palestine Liberation Organization, except under onerous conditions. In 1979, Begin actually succeeded in getting from Egypt’s Anwar Sadat a fully separate peace, formally de-linking peace with a major state and the conflict with the Palestinians. After the 1993 Oslo Accords, Shimon Peres revived what can be called “soft linkage” by creating the Casablanca process of economic ties with Arab states to build on the goodwill of that Israel-PLO accord, but that effort fizzled when Oslo itself lost its sheen. But by specifically agreeing to suspend moves toward West Bank annexation as part of the normalization deal with the Emirates, it was Netanyahu who directly reinserted linkage in a bilateral agreement with an Arab state.

In theory, the idea that Israel would reap dividends in terms of its inter-regional relations from concessions it made to the Palestinians has been on the table since the Saudis proposed the “Arab peace initiative” in 2002, promising the nirvana of full relations with all Arab (and, by extension, Muslim) states in exchange for the fantasy of Israeli full withdrawal to the 1967 borders. But the UAE accord shrunk this down to size, transforming a hypothetical possibility into a tangible reality.

ADDITIONAL DEMANDS?

Now that a Likud prime minister has endorsed the principle that Israel will accede to the demands of faraway Arab states on matters related to the Palestinians in exchange for the embrace of full relations, it is not unreasonable to expect additional demands from other Arab states considering normalization of ties with Jerusalem. This raises a series of provocative questions.

Would, for example, Israel consider restricting settlement growth on the West Bank or transferring additional territory to Palestinian control in exchange for formalizing ties with other major states, like Morocco, or groups of states, like the smaller Gulf countries? And, no less importantly, would the Palestinian leadership drop its self-defeating opposition to the emerging tide of Arab normalization with Israel and work with Arab capitals to maximize the benefits it could accrue from this new development? Alternatively, Israel may just try to re-sell its restraint on annexation to other Arab states. In this case, the decision will be for Jerusalem’s Arab suitors to make—does this “recycled linkage” provide enough cover to reap the advantages of open bilateral ties? Precisely whether and how linkage evolves in emerging relationships between Israel and Arab states is one of the most consequential—and certainly one of the most intriguing—follow-on questions from the UAE breakthrough.

As momentous as the UAE-Israel accord may be, in some ways it is also smaller than it seems, too. This is not to diminish either the substance of the breakthrough of the intent of the principals—the Emirate’s trail-blazing leader, Crown Prince Muhammed bin Zayed, or Netanyahu, who has reaped great dividends from efforts during his prime ministry to expand Israel’s global reach. Rather, it is to recognize what should be obvious—that the establishment of full, normal relations is, for both, a choice, not a necessity. And depending on the circumstances, both could turn away from this choice without suffering a major strategic reversal.

In this respect, the Emirates is different from Egypt or Jordan, both of which needed peace with Israel to address fundamental existential challenges—for Anwar Sadat, the need to regain territory and, through peace, reorient Egypt to the West; for King Hussein, the need to protect Hashemite equities following the surprise Israel-PLO deal at Oslo. Similarly, Israel today—powerful, vibrant, self-assured — is not the Israel that grudgingly returned every inch of Sinai in order to take Egypt out of the Arab war coalition or that gave the Hashemites a contractual guarantee of their role in Jerusalem in order to lock Jordan into a long-term accord to safeguard its Jordan River security border. Israel and the Emirates have no common border, no territorial dispute and no existential or ideological challenge wrapped up in public reconciliation. Both will undoubtedly reap substantial benefits from their normalization agreement, but none will approach the strategic significance of what Egypt and Jordan won via their peace treaties with the Jewish state—and vice versa.

What the UAE does have in common with Egypt and Jordan is the fact that it will earn considerable benefits of its deal with Israel in terms of relations with Washington. In the realm of technology, the UAE gains access to high-tech weaponry otherwise restricted because of concerns its delivery would upset Israel’s qualitative military edge. In terms of politics, the UAE gains a measure of immunity from the much tougher policy vis-a-vis Arab authoritarian regimes likely to be adopted by the Democrats, should Joe Biden win the White House in November—not full immunity, of course, but Arab leaders at peace with Israel enjoy a different status than Arab leaders not at peace with Israel. On these two key issues—access to advanced technology and protection from criticism of the Emirates’ interventions in Yemen and Libya—just having open relations with Israel may not be enough; rather, as is often the case with Cairo and Amman, it may take the ongoing advocacy of Israeli and pro-Israeli representatives on the Hill to provide the Emiratis the political cushion they most likely believe they have earned from normalization.

But there is an important difference that is a key corollary to all this: Precisely because the strategic stakes are much lower for the two parties to the UAE-Israel agreement than is the case for Israel’s other Arab peace partners, the cost either would bear should the relationship break down would be much lower than if Egypt or Jordan were to break ties with Israel. It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the Emiratis freeze or reverse aspects of normalization—in response to some particularly objectionable Israeli step vis-a-vis Palestinians, for example, or in the event Israel and post-Erdogan Turkey decide to kiss and make up. But distance matters. The Emirates could downgrade its relations, withdraw its ambassador and place restrictions on Israeli tourists and the repercussions would be manageable for all sides; Egypt and Jordan—which have done this at times over the course of their peace with Israel—have more at stake in relations with their next-door neighbor and potentially face more serious consequences (a phenomenon which works in both directions, one should add).

BENEFITS AND DANGERS

For its part, Israel will enjoy substantial benefits from normal relations with the Emirates, both in terms of the bilateral opportunities that it can develop with the enterprising, welcoming people of an influential Gulf state that, like Israel, punches above its weight on the international stage, and the potential follow-on impact of expanding ties with other Arab and Muslim nations. But formalizing ties with the UAE does not resolve or even fundamentally alter any of Israel’s other strategic challenges—whether it is the nuclear threat from Iran, the missile threat from sub-state actors on its borders, or the binational threat from the unresolved conflict with the Palestinians. Just as with the Emirates, for Israel too the stakes of normal relations are lower than with previous peace partners.

One arena in which others will determine the impact of the UAE-Israel deal will be in terms of the opposition it engenders among its enemies. Egypt, one should recall, suffered for its go-it-alone peace treaty with Israel with a decade of ostracism from the Arab world, but eventually those other countries reconciled with Cairo on its terms, not theirs. Since then, numerous Arab countries have hosted senior Israeli ministers, trade missions and sports teams, with little pushback even from the region’s radicals. On this score, times have indeed changed.

The loudest critics of the UAE-Israel deal were Turkey and Iran—ironically, non-Arab Muslim states that were Israel’s closest regional partners at the dawn of the peace process but which have obviously undergone sharp reversals since then. The operational question is whether their outrage at the deal will take more substantive form than just harangues on their favorite satellite channels. Given the strength of the Israeli and Emirati economies, boycotts by critics of the Jerusalem-Abu Dhabi partnership will be ineffectual and likely hurt the boycotters more than their intended victims. What matters is whether Tehran, Ankara and local proxies like Hezbollah and Hamas will target Israeli and Emirati assets—especially signs of their partnership, like embassies, joint ventures, airlines and tourist sites—for terror attacks. Even if that were to happen, one should not necessarily jump to the conclusion that outrage over the UAE-Israel deal was itself the trigger. Given existing regional competitions and animosities from Libya through the Gulf, it may be difficult to determine whether this new Arab-Israel partnership is the proximate cause of any particular action or just the handiest excuse.

Lastly, the UAE-Israel deal is “smaller” than popularly conceived in terms of the American role. To be sure, the Trump Administration deserves great credit for recognizing that widening the circle of Middle East peace via full UAE-Israel relations would advantage US interests far more than blessing Israel’s disastrous move toward West Bank annexation, and for then investing its weight in bringing about that normalization agreement. But the potential for that disaster owes itself to President Trump’s own short-sighted promise last January to recognize territory Israel might annex in accordance with the Trump peace plan, followed by his administration’s refusal to walk back that senseless offer. Indeed, presidential advisor Jared Kushner himself seems to have recognized that the UAE-Israel deal was as much as anything a way to stymie that American initiative when, in a tacit show of great candor, he authored a Washington Post op-ed extolling the UAE-Israel deal that made no specific mention of the Trump peace plan.

NETANYAHU’S LADDER

Like all good policy decisions, the UAE-Israel deal is the result of the enlightened self-interest of the key parties. The Trump administration came to realize that Israeli annexation of West Bank territory would have sounded the final death-knell for the President’s peace plan and was open to ways to help Netanyahu climb down from his commitment to pursue it in order to avoid that political embarrassment. (The idea, advanced by some analysts, that annexation was a brilliant bluff by Netanyahu to provide leverage for the normalization deal is especially ill-informed; if Kushner had not held out against the entreaties of US ambassador David Friedman or if Israel’s COVID count had not escalated dangerously and taken annexation off the political agenda, all signs point to the fact that Netanyahu would have followed through on his political promise to pursue it.)

The Emiratis realized that they could earn substantial benefit from both this Administration and its potential successor if they stepped in to provide the ladder to help Netanyahu climb down from the annexation tree. And Netanyahu himself reached the conclusion that the practical benefits of normalization with a major Gulf state outweighed the ideological satisfaction of annexation, a fact that took on greater importance as Joe Biden’s electoral prospects brightened in recent months, thereby increasing the risk that annexation would drive a wedge into the all-important relationship with Washington.

The result should not be exaggerated or minimized—the establishment of normal UAE-Israel relations is neither a moment of cosmic transformation in the regional balance of power, nor is it merely the product of an inevitable evolution of past quiet relations, a footnote to history, quickly to be forgotten. Rather, it should be recognized for the landmark event that it is, both practically and psychologically: a highly significant though still incremental step on the hundred-plus-year march toward legitimizing the idea of a Jewish state in the Middle East. Indeed, the fact that it is a partnership of choice, not a partnership of need, makes it especially worthy of celebration.

Robert Satloff is executive director of The Washington Institute. This article was originally published on the Times of Israel website.