The Russian president was forced to make peace with Yevgeny Prigozhin, whom he described as a ‘traitor,’ in a Russia he described as on the brink of ‘civil war.’

Back to normal in Russia: On the Wildberries online store, products with the “Wagner” logo are back in stock. On the highways south of Moscow, the pavement, ripped up the day before with a backhoe, is being resurfaced. Just some of the evidence of a country in a hurry to forget an episode as brief as it was dizzying: The rebellion of a private militia which, in the space of a single day on Saturday June 24, managed to seize a city of one million inhabitants and get within 200-300 kilometers of the capital without encountering any serious resistance.

The criminal investigation opened against Yevgeny Prigozhin for “calling for armed insurrection” has been closed − the announcement was made by Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov. Even the Ministry of Defense considers the incident closed. On its social networks on Saturday evening, the ministry posted a photo proclaiming “cohesion and unity.” The damage caused by the Prigozhin adventure is to be written off: Russian military bloggers put the losses at between 13 and 20 in the ranks of the army, almost all of them killed aboard downed aircraft (six helicopters and one plane).

Nineteen buildings in the Voronezh region were also hit by the fighting, and the Voronezh refinery was still on fire on Sunday. However, on Sunday, Andrei Kartapolov, the head of the Duma’s defense committee, said authorities that there was “no reproach” to be leveled at the mercenaries: “They didn’t hurt anyone, they didn’t break anything,” he said.

In Rostov-on-Don, the epicenter of the crisis, life has also returned to normal. On Saturday evening, Wagner fighters and the armored vehicles they had deployed in the city began to leave, to the cheers of residents − a mixture of relief for avoiding bloodshed and support for Prigozhin’s anti-elite rhetoric. The Kremlin will not fail to notice the affection shown to the putschists by a section of the population.

A crisis that will be hard to forget

The crisis ended as abruptly and surprisingly as it began. But will it be forgotten so easily? Firstly, we only know the broad outlines of the agreement reached under the auspices of Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko, which led to a peaceful resolution. Prigozhin has saved his head, at least temporarily: the charges against him have been dropped and the St. Petersburg businessman is to be welcomed to Belarus. His political adventure − which he described as restoring “order and justice”? − has come to an end, perhaps also momentarily.

The result is not insignificant, bearing in mind that it was probably the decision to do away with Wagner and its leader that motivated the insurrection. What about his men? Those who did not take part in the mutiny will be able to sign a contract with the Ministry of Defense, according to the Kremlin. The others are returning to their base camps. What happens next? Will they be disarmed? When Prigozhin announced on Saturday evening that he was giving up the confrontation, he took it for granted that Wagner would not be dismantled.

The former gangster later known as “Putin’s chef” has played his cards right: on Sunday, the return of the columns of troops launched against Moscow, on the M4 freeway, but this time heading south, allowed observers to get a sense of the scale of the operation. According to news site Baza, which is linked to the security services, no fewer than a thousand vehicles of all types, from minibuses to air defense systems, divided into four columns, were on their way to attack Moscow. This is in addition to the troops amassed in Rostov.

Despite the size of the force involved, the humiliation was complete for the army, which proved incapable of putting an end to the expedition and was preparing to defend the capital by piling sandbags on its access roads. Some of the units that came face to face with Wagner’s men refused to fight, whether out of fear or sympathy. The consequences on the Ukrainian front are still difficult to assess.

But when all is said and done, Putin has no doubt fared the worst. The only bright spot was the unity of the political elite: all day Saturday, lawmakers, governors and local councilors broadcast messages of support for the president. If Prigozhin had hoped to rally support to take power, this part of his gamble was a failure. The elite chose the relative stability offered by Putin. Some of its members can also take comfort in the fact that the president’s reaction − accepting the affront rather than risking a bloodbath − also shows that Putin is still in touch with reality and capable of compromise.

Putin ‘weak’ and ‘out of step’

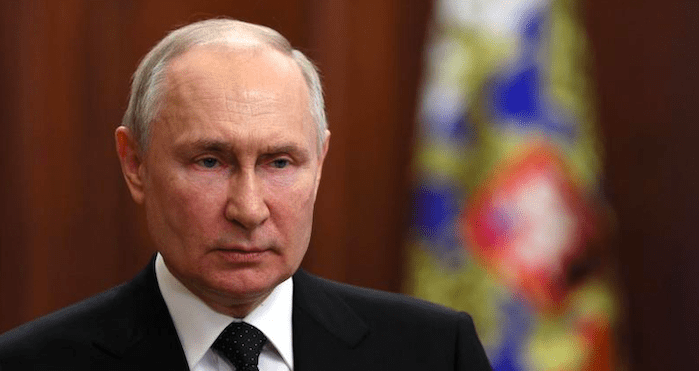

Other than that, the head of the Kremlin appeared weak or out of step at every stage of the crisis. For months, he remained silent in the face of Prigozhin’s provocations and insults, allowing the wound to fester. His speech on Saturday morning represented a radical change of tone. In his remarks, the president described a Russia on the brink of “civil war.” His parallels with the 1917 revolution placed him, surprisingly, in the shoes of the loser, Tsar Nicholas II.

From now on, Putin will have a hard time explaining to Russians that, despite the seriousness of the confrontation with the West (the aggressor, in his view), they can go on living normally. It’s also impossible to claim that things have gone “according to plan,” as Prigozhin put it on Saturday evening. The climate has changed even in the capital, where everyone has become aware of the extraordinary nature of the situation. “It’s like the 1990s,” one passer-by murmured on Saturday in central Moscow. “Bands of organized gangsters settling their scores in the suburbs… Except that now they have tanks and planes…”

More seriously, the Russian president’s subsequent attitude appeared to be in complete contradiction with this martial tone. Without mentioning him by name, Putin described Prigozhin as a “traitor” − a designation which, in theory, carries a death sentence. Instead, in the evening, the head of the Kremlin found himself having to offer his subordinate security guarantees… It is no longer just the institutions of the state that have been insulted, but the president himself.

This is not just a question of offended pride, but of the way Putin’s Russia works. “For the elites, only one thing really counts,” said exiled journalist Maxim Trudolyubov, “that is the leader’s ability to hold the levers of control firmly. Yet it’s now clear that the president of the Russian Federation doesn’t even control “his own people,” and that at some point they may become a threat to the whole group.”

Regime change no longer taboo

The very idea of a change of power, previously taboo, is now part of the landscape. The fact that Prigozhin was unable, or unwilling, to go through with his plans does not change the fact that power is far from being as inaccessible as it might have seemed. “Everyone saw that the system was riddled with holes,” summarized Abbas Gallyamov, who was an adviser to Putin in the 2000s.

In a way, this observation also applies to diplomacy. During the crisis, Russian diplomacy had to do its utmost to reassure its neighbors − resulting in surreal communiqués such as: “The Prime Minister of Armenia has been kept informed of the situation in Russia.” We also learned that North Korea had offered to help.

On the domestic front, the situation is likely to worsen. The hunt for traitors is set to escalate, as it turns out that they are everywhere, even among those whom the Kremlin has nurtured in its bosom. “After losing face like this, Putin can only choose terror,” wrote blogger Anatoli Nesmiyan on Telegram. “The coward is always furious when he has been forced to expose his cowardice for all to see.”