On January 25-27, 2016, several hundred Muslim religious leaders from throughout the world and fifty non-Muslim observers met in the beautiful city of Marrakesh under the patronage of the King of Morocco to discuss and promote the “Marrakesh Declaration” on “the Rights of Religious Minorities in Predominantly Muslim Majority Countries.”

Marrakesh is a popular place for declarations and agreements and has been the site for other declarations on topics such as preventing corruption and stopping illicit wildlife trafficking. It was even the site of another international conference promoting religious tolerance in the Middle East, in November 2011.[1]

Although held under the auspices of the Moroccans, the January 2016 meeting was organized through the Abu Dhabi-based Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies. The Forum is one of several projects led by Mauritanian-born Sheikh ‘Abdallah Bin Bayyah.[2] The Forum’s laudable purpose is “a long term vision in eradicating the extremist narrative through the use of a Primary Narrative that seeks to establish itself through via the sources of Islam, one that is based on the promotion of peace, and human compassion.”[3]

Although very much part of the mainstream Islamic establishment in the Middle East, Bin Bayyah is a somewhat controversial figure in the United States, especially because of his long-standing ties with organizations and Islamist causes championed by Sheikh Yousuf al-Qaradhawi.[4] Al-Qaradhawi’s strident support for the Muslim Brotherhood, especially in the past few years, included openly espoused anti-Semitism,[5] a charge the Qatar-supported cleric denied.[6]

Bin Bayyah broke with Al-Qaradhawi’s International Union of Muslim Scholars (IUMS) in 2013 and was cited by President Obama during a 2014 UN speech as a role model against extremism.[7] His fatwa against ISIS was also cited as material to be propagated by a U.S.-UAE counter-terrorism media center established in July 2015.[8]

In full disclosure, I once met Sheikh Bin Bayyah in Washington, D.C. while working for the Department of State. He was a courtly gentleman very much in line with senior Muslim clerics one often meets in the Arab world. On that occasion, he was bemused that in the many meetings he had that evening, among many visiting American Muslim figures of South Asian origin, the only two visitors who could speak to him in conversational Arabic were two non-Muslims, myself and an Arab-American Christian who was also a government employee.

The elderly cleric also played a key role in the 2010 New Mardin Declaration which sought to address one of the basic pillars of the takfiri Salafi Jihadist movement, some 14th century fatwas of Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328). A fierce Hanbali cleric, Ibn Taymiyya’s condemnation of the semi-Islamized Mongol Il-Khans as no better than infidels (Kufar) set the stage for the much later takfiri extremists of the 20th century and beyond to declare any Muslim they disagreed with as infidels deserving death. Ibn Taymiyya was also an early intellectual fount of anti-Shi’a vitriol which was also adopted by the modern devotees of what would become ISIS.[9]

The New Mardin Declaration conference has been criticized as poorly organized and academically dubious but there is no doubt that its revisionism towards Ibn Taymiyya’s writings provoked a bitter response in Arabic by influential pro-Al-Qaeda clerics such as Akram Hijazi and Hamid Al-Ali.[10] While it seems to have had very little effect in the continued rise of Salafi Jihadist terror, the conference did generate a slew of positive media coverage in the West, often promoted by Bin Bayyah’s mediagenic student, the American convert Hamza Yusuf Hanson.[11]

In many ways, Marrakesh is a larger and broader repeat of Mardin, seeking “to use age-old Muslim texts to refute current-day religious arguments by Islamist groups.”[12] In the case of Marrakesh 2016, the document in question is the so-called Charter of Medina, supposedly drafted by the Prophet Muhammad for the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants of that city.[13] The conference’s organizers frankly admitted that they aim to “begin the historic revival of the objectives and aims of the Charter of Medina, taking into account global and international treaties and utilizing enlightening, innovative case studies that are good examples of working towards pluralism.”[14]

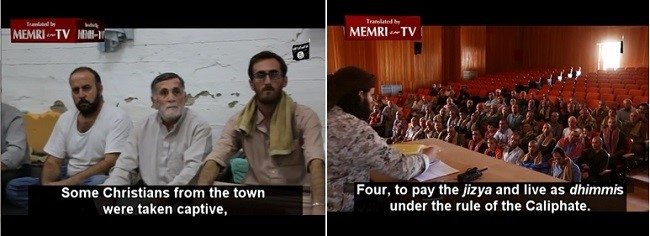

Certainly, the topic of protecting the rights of religious minorities in Muslim majority countries could not come at a better time. The rise of the Islamic State since 2014, and especially its treatment of Yazidi and Christian minorities in Iraq and Syria, and by the ISIS branch in Libya, has shined a bright global light on the issue.[15] Such actions by the Islamic State have directly contributed to anger directed against the Muslim diaspora in the West.

But ISIS builds on a much larger Islamist discourse, grounded on selective readings of the sacred texts of Islam, calling for violence against religious minorities, most prominently Christians, which goes back decades.[16] Such a backdrop is very much on the minds of the Marrakesh Declaration’s drafters who noted (without mentioning ISIS, Al-Qaeda or Salafism) that the situation in the Middle East “enabled criminal groups to issue edicts attributed to Islam, but which, in fact, alarmingly distort its fundamental principles and goals in ways that have seriously harmed the population as a whole.”[17]

While Bin Bayyah has been active on this front for years, the conference can also broadly be seen as part of a range of UAE-supported or funded initiatives against Islamist extremism. This includes the Sawab Center and Hedayah CVE Center of Excellence, action against the Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters, and laws against hate crimes and discrimination.[18] Marrakesh 2016 also clearly builds on the 2007 “A Common Word” Muslim outreach to Christians, also signed by Bin Bayyah.[19]

And while the United Arab Emirates has been in the forefront of fighting Islamist extremism, the Kingdom of Morocco has not been far behind and also attracted the ire of the Islamic State. A January 2016 ISIS video campaign against North African governments included a lengthy bitter attack against traditionally tolerant Moroccan Islam, singling out the “100,000 shrines of polytheism” ISIS would like to destroy. Targeting Moroccan Sufis seemed almost as important as targeting the Moroccan Government.[20]

The Declaration clearly affirms that “it is unconscionable to employ religion for the purpose of aggressing upon the rights of religious minorities in Muslim countries.” One of its weaknesses, however, is that it is lacking in real concrete (and especially, immediate) steps to be taken. There is a potentially significant call for Muslim scholars to come up with a new jurisprudence that incorporates a diverse and tolerant concept of citizenship. There is a request for a review of educational curricula in order to eliminate material that promotes extremism. There are the usual calls for political and “educated, artistic and creative” leaders to strengthen religious understanding and respect for minority rights.

An interesting, if loaded and unrealistic, paragraph seems to blame the victim or call for a return to an idealized and complex past long gone asking “various religious groups bound by the same national fabric to address their mutual state of selective amnesia that blocks memories of centuries of joint and shared living on the same land; we call upon them to rebuild the past by reviving this tradition of conviviality.”

One wonders which part of those shared centuries of “traditional conviviality” are to be recalled and applied? The history of religious minorities under Islamic rule is an incredibly complex and varied one. But while it can – at some specific times and places – compare favorably with Western Christian rule over religious minorities, it also includes more than its fair share of ugly massacres and brutality. Minorities could be favored as a group, or singled out for savage oppression (much in the same way Jews were treated by Western Christian rulers for centuries) based on the passing whim or renewed zeal of whatever Caliph or Sultan happened to rule.[21] There is at least a whiff of happy Ahl al-Dhimmah talk, of nostalgia for religious minorities content under their Muslim masters, in this section.[22]

The actual Marrakesh 2016 Declaration text, appearing in English on January 27 (as of January 30 there seemed to be no Arabic version and videos of the plenary were not available to the general public) was quickly lauded by Texas mega-church pastor Bob Roberts who called it a “huge first step,” and enthusiastically, if inaccurately, noted that “there has not been a statement like this since the Medina Charter from the prophet Mohammed, that’s why this is so big.”[23] Retired Roman Catholic Cardinal Theodore E. McCarrick, former Archbishop of Washington, D.C. spoke for all the interfaith observers present:

“I was privileged to have listened to the declaration of our final gathering. It is truly a great document, one that will influence our times and our history. It is a document that our world has been waiting for and a tribute to the Muslim scholars who prepared it. As one of the People of the Book, I thank you for this document and I thank the Lord God who has provided his followers the courage to prepare this document. I will be honored as an observer to support it.”[24]

Those closer to the action in the Middle East were more sanguine. Although he was not able to attend in person, the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch of Baghdad Louis Sako, provided a more practical, immediate and ground zero-based view of life in government-controlled parts of Iraq, in a statement circulated at the conference, citing (without including the better known depredations of ISIS):

“Muslim contractors refusing to build homes, monasteries, etc., for Christians, whom they identify as infidels; the display of posters, even in public offices, asking Christian girls to wear a veil, following the example of Mary; a judge in Baghdad who dismissed a Christian from court, claiming that Christians are not accepted as witnesses in Iraqi courts; and militias in Baghdad who confiscated homes, lands and other properties of Christians.”[25]

Other observers noted the hopeful presence of Syrian and Iraqi Christians, a Yazidi and a Druze, but also the “difficult to support” hardcore assertions by Saudi and Pakistani representatives denying any religious discrimination in their countries.[26] Also attending was prominent Orthodox Rabbi David Rosen, board member of the King Abdullah International Dialogue Centre (KAICIID).[27]

Still another Catholic expert on the Middle East, Fr. Jean Druel, while praising the effort to reinterpret the Medina Charter within a contemporary context and noting that this attempt would not please the Salafists, wondered “what happens when you violate this charter?”[28]

And that is one key flaw of this Declaration. How does a document better known for its existence on paper rather than as a practical model serve as a modern counterweight to extremism? The Salafi Jihadists also make the same appeal to the foundational documents of formative Islam and find ample justifications for their extremism and violence there ready to be cherry-picked and applied to the contemporary world.

14th century depiction of the surrender of the Jewish Banu Nadir tribe

ISIS self-consciously treats minorities in ways that mimic early Islam, drawing from the much more historically consequential “Pact of Umar” made with conquered Christian populations.[29] Some scholars have even doubted the authenticity of the Medina Charter, suggested it may be a compilation of two documents and questioned especially the portions mentioning the treatment of the Jews of Medina, the very part of the Charter that gives it that timely inter-religious dimension. They note that the Jews of Medina were not treated as individual tribes but as bound associates of Arab tribes. In fact, the three Jewish tribes are not even mentioned by name.[30]

Given that the Medina Charter is dated traditionally from 622 A.D., it would be worthwhile noting how religious minorities were actually treated in the supposed time of its viability under Muhammad’s rule. The historic record, such as it is, is not a heartening one. The fate of the Jewish tribes of Medina is a well told tale still found in many Arab textbooks. The Banu Nadir and Banu Qaynuqa were expelled en masse for violating the terms of their “contract” two years after the Medina Charter. Not surprisingly, one of the elements of the Charter and of the treatment of the Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Nadir is the concept of collective responsibility/punishment documented frequently in ordinary Islamist discourse to this day.[31]

The liquidation of the third Jewish tribe, the Banu Qurayza, is another well-known story, even included in fifth grade ISIS textbooks.[32] This tribe was accused of rebellion after the Battle of the Trench (627 A.D. – five years after the Medina Charter) and was allowed to choose a mediator from an Arab Muslim tribe traditionally allied with the Banu Qurayza. That mediator, Saad Ibn Muadh, a man much beloved by the Prophet Muhammad, decreed that all the men of this Jewish tribe were to be beheaded and the women and children sold into slavery.

The extermination of this tribe was actually cited by ISIS as a model for the mass murder of a rebellious Syrian Sunni Arab Muslim tribe in 2014.[33] And showing how compelling is the memory of those events, Saad Ibn Muadh’s ruling on the Banu Qurayza 14 centuries ago was cited as recently as a few months ago in Gaza as a model for finishing with the Jews during the “Stabbing Intifada.”[34] American Salafi preacher Yasir Qadhi also used Ibn Muadh’s death sentence in 2013 as a positive teaching moment on principled leadership.[35]

It is easy to find similar ugliness in the past of many faith traditions and we are talking here not so much about the historical record but of widely held perceptions about history. But can a narrative base itself on the alleged tolerant nature of the Medina Charter while divorcing itself from the alleged punitive treatment of the Jews of Medina? Can resurrected visions of “traditional conviviality” be so promoted given the way that Jihadists use both Islamic proof texts and selective readings of historical events to justify their violence?

Given the growth of Islamist-fueled intolerance in many Muslim majority countries, any call for tolerance and better treatment of religious minorities is to be unambiguously welcomed. Despite the lack of the words “equality” and “individual” rights in the Marrakesh 2016 Declaration, it is a step in the right direction. It is hard to believe, however, absent any acceptance by many Muslim states (including some, like some unnamed representatives from Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, already on record at the conference that they don’t discriminate) that these fine words will have much immediate effect.

While reforming the educational curriculum and reformulation of fiqh are laudable goals, they pale into insignificance with the present emergency that is a battered and dispossessed Yazidi community, a Mosul Christian community robbed of all they possessed at gunpoint and ancient communities region-wide emptying from a Middle East where they see no future, no economic stability or personal security.[36] After the textbooks are eventually purged and the jurisprudence is spruced up, what will remain of actual, living communities?

Furthermore, how do such conferences and declarations, replete with compromised figures drawn from often discredited regime elites, move the needle in the discourse of the common people, especially the already alienated young? The statements of established Islamic clergy and governments over the past decades have already failed to prevent the rise of Al-Qaeda and ISIS and a seemingly inexorable move towards various types of Islamism. Isn’t the obvious solution the promotion of civil codes and secular states?[37]

While using the Medina Charter as a tool to fight the Islamists on their own territory is an interesting, even bold, concept, it would seem to fall short. In the end, drawing from an idealized version of Islamic history is no substitute for individual rights and the enforcing of a rule of law that fully protects those rights. If a 1400-year-old “constitution” that never seems to have actually been used helps to secure those modern rights and that rule of law, then that is great.

If not, the 2016 Marrakesh Declaration will join many other well-intentioned but empty expressions of good will that generated some nice, fleeting headlines among the enthusiastic and uninformed but little more. One can only wish the organizers and those frontline states supporting them the very best and encourage that gestures can be rapidly transformed into public policy in a region that seems emptying of rights for all of its people, but especially its minorities.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice-President of MEMRI.

Endnotes:

[1] Religionsforpeace.org/publications/marrakech-declarationn.

[2] “Why American Needs To Know This Man”, Souheila Al-Jadda and Amina Chaudary, The Islamic Monthly, March 4, 2014.

[3] Marrakeshdeclaration.org/organizers.html

[4] “Exclusive: Banned Cleric’s Outspoken Deputy Visits White House”, Steven Emerson and John Rossomando, IPT News, June 26, 2013.

[5] Youtube.com/watch?v=HStliOnVl6Q, Feb 10, 2009.

[6] Youtube.com/watch?v=il5xam68ams, December 29, 2010.

[7] “Prominent Muslim Sheikh Issues Fatwa Against ISIS Violence”, Dina Temple-Raston, NPR, September 25, 2014.

[8] http://www.thenational.ae/world/middle-east/abu-dhabi-counter-terrorism-centre-to-battle-isils-online-lies#page2

[9] “Zarqawi’s Anti-Shi’a Legacy: Original or Borrowed?”, Nibras Kazimi, Hudson Institute, November 1, 2006.

[10] “Ibn Taymiyya’s ‘New Mardin Fatwa’. Is genetically modified Islam (GMI) carcinogenic?”, Yahya Michot, Hartford Seminary, 2011.

[11] “Ibn Taymiyya’s ‘New Mardin Fatwa’. Is genetically modified Islam (GMI) carcinogenic?”, Yahya Michot, Hartford Seminary, 2011.

[12] “Muslim scholars recast jihadists’ favourite fatwa”, Tom Heneghan, Reuters, March 31, 2010.

[13] Constitution.org/cons/medina/con_medina.htm

[14] Marrakeshdeclaration.org/about.html

[15] “The ISIS Caliphate and the Churches”, Alberto M. Fernandez, The Middle East Media Research Institute, August 27, 2015.

[16] Kepel, Gilles, Muslim Extremism in Egypt, the Prophet and the Pharaoh. London: Al-Saqi Books, 1985.

[17] Marrakeshdeclaration.org/marrakesh-declaration.html

[18] “New UAE law: 10 years’ jail for hate crimes and discrimination”, Gulf News, July 20, 2015.

[19] Acommonword.com

[20] “ISIS Launches Campaign Urging North African Muslims, Al-Qaeda Members To Join Its Rank, Target Local Governments”, MEMRI Jihad and Terrorism Threat Monitor Project, January 21, 2016.

[21] An-Na’im, Abdullahi A. “Religious Minorities under Islamic Law and the Limits of Cultural Relativism,” Human Rights Quarterly. Vol. 9, No. 1, February 1987, pp. 1-18.

[22] Youtube.com/watch?v=RN4x8TvK8Xw, June 13, 2014.

[23] “A Muslim Declaration on Religious Minorities: An Interview w/ Pastor Bob Roberts in Marrakesh, Morocco”, Ed Stetzer, Christianity Today, January 28, 2016.

[24] “Muslim leaders reiterate support for minority rights in Islamic nations”, Catholic News Service, January 27, 2016.

[25] “Chaldean patriarch details acts of discrimination against Christians”, Catholic News Service, January 28, 2016.

[26] “La déclaration de Marrakech, un texte qui fera date pour les minorités religieuses?”, Loup Besmond De Senneville and Anne Bénédicte, La Croix, January 29, 2016.

[27] “‘Move Beyond Discussion to Implementation’: KAICIID SG Urges Audiences at Conference on the Rights of Religious Minorities”, PR Newswire, Jaunary 28, 2016.

[28] “La déclaration de Marrakech, un texte qui fera date pour les minorités religieuses?”, Loup Besmond De Senneville and Anne Bénédicte, La Croix, January 29, 2016.

[29] “Medieval Sourcebook: Pact of Umar, 7th Century?”, Paul Halsall, Forham University, January, 1996.

[30] “Reflections On The ‘Constitution Of Medina’: An Essay On Methodology And Ideology In Islamic Legal History”, Anver Emon, UCLA Journal of Islamic & Near Eastern Law, Spring/Summer, 2002.

[31] Youtube.com/watch?v=ya3mVKODSyQ, February 1, 2011.

[32] Twitter.com/VPAFernandez, October 29, 2015.

[33] “Massacre And Media: ISIS And The Case Of The Sunni Arab Shaitat Tribe”, Alberto M. Fernandez, The Middle East Media Research Institute, June 23, 2015.

[34] “Rafah Cleric Brandishes Knife in Friday Sermon, Calls upon Palestinians to Stab Jews,” MEMRI TV Clip #5098, October 9, 2015.

[35] Youtube.com/watch?v=UZE1N56fswY, June 11, 2013.

[36] “Is This the End of Christianity in the Middle East?”, Eliza Griswald, The New York Times, July 22, 2015.

[37] “Former Iraqi MP Sayyed Ayad Jamal Al-Din in a TV Debate about Separation of Religion and State: The Combination of the Koran and the Sword Is More Dangerous tan Nuclear Technology”, The Middle East Media Research Institute, November 28, 2010.