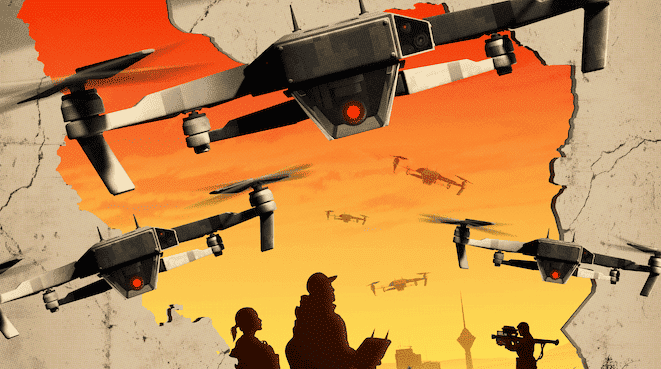

A potent new fusion of old-style human spycraft with cutting-edge technology is having a big impact on high-stakes conflicts.

By

Daniel Michaels

When Israel launched its 12-day attack on Iran in June, a network of secret agents on the ground proved critical in crippling Tehran’s defenses. Some of the most secret operatives weren’t professional spies or commandos in camouflage. They were ordinary locals empowered by Israeli high-tech gadgetry.

Israel’s intelligence agency, Mossad, had spent years identifying and cultivating inside Iran a silent force, including victims of Iranian repression, ethnic minorities sidelined by regime policies, and people from Afghanistan and other neighboring countries who can live and work openly in Iran. At secret camps outside Iran, Israel trained its recruits to operate sophisticated automated and remotely controlled equipment, according to people familiar with the operation.

Then Mossad instructed them to go about their daily routines across Iran, as part of what it calls a “drawer operation”—one that sits quietly in reserve until the drawer needs to be opened. That day was June 13, when the strategically located agents used rockets, drones and other weapons smuggled into Iran to destroy nearby air-defense systems and missile launchers, according to Israeli statements and people familiar with the operation.

Weeks earlier, Kyiv had used a similar playbook to attack Russia’s strategic bomber fleet with explosive drones. Ukraine’s real-life version of James Bond, Artem Tymofeyev, is a bearded DJ who posted on SoundCloud under the name Tim and had worked at his father’s Russian flour mill. Tymofeyev and his wife, a tattoo artist, secretly prepared Operation Spiderweb from inside a warehouse they rented near a Russian state security office, according to Russian and Ukrainian officials.

Like Israel’s agents in Iran, Tymofeyev and his wife are ordinary people who easily blended into Russian society. But they employed advanced technologies supplied by their spymaster-handlers back in Kyiv.

Over the past year, Ukraine and Israel have displayed a potent new fusion of old-style human spycraft with cutting-edge gear, giving clandestine action an outsize impact on high-stakes conflicts. The transformation has been made possible by increasingly compact electronics, batteries and explosives. Miniaturization, especially of power supplies, lets spy agencies equip field agents with capabilities unimaginable a few years ago.

Until recently, achieving big impact at close range in unfriendly territory generally required putting elite career operatives directly in harm’s way. Now, with the advent of powerful remote or autonomous devices, the people deploying them don’t need to be seasoned professionals. Amateurs with minimal training can execute critical elements within larger missions, such as planting devices or operating them near hard-to-reach targets. Being local, they can remain hidden or escape before an attack.

“The lone 007 operator is not what we’re looking for now,” said Eran Lerman, a former top official in Israel’s National Security Council and senior military-intelligence official. “Now, people are at the tip of a very complex operation.”

Spy agencies have long made innovative use of technology, including devices more fanciful than those James Bond gets from Q, his gadgetry wizard. Technology is also wielded against spies, and that threat is precisely why intelligence organizations are now seeking local agents from outside their ranks.

Pervasive surveillance, electronic tracking and biometric profiling—together known as “digital dust”—have gutted traditional undercover operations. The U.S. discovered that in 2003, when a team of almost two dozen agents who had abducted an Egyptian cleric in Italy for secret interrogation was outed by analysis of their local cellphone records.

Mossad was similarly upended by technology in 2010, when an entire team sent to assassinate a Palestinian official in Dubai was exposed by security cameras. Local police published stills from the footage and photos of the agents from their forged passports, blowing their covers.

The fiasco followed a botched attempt by Mossad agents in 1997 to assassinate a Palestinian leader in Jordan that sparked a diplomatic crisis and demonstrated limits to Israeli operatives’ ability to act abroad.

Mossad’s two failures shocked an organization accustomed to operating with impunity. Its agents in 1960 had kidnapped Nazi Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and spirited him back to Israel for trial. After Palestinian terrorists killed 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Mossad agents spent years crossing the globe to hunt down and kill the assailants.

Spy agencies saw profound implications in the recent debacles, far beyond public humiliation. Traditional spy tools and methods—known in the field as “tradecraft”— suddenly seemed unusable. Forged passports became evidence of crimes. Cellphone-network data from secret calls offered a trail of breadcrumbs for investigators. Facial-recognition software and DNA analysis made wigs and disguises laughable.

“The impact of biometrics was enormous,” said Alon Kantor, an Israeli investor who specializes in security technology.

Not long ago, a few documents could establish a fictitious identity. In a digitized world where almost everyone has some degree of online presence, lacking an internet persona becomes suspicious, Kantor noted.

Former Israeli intelligence officials say they realized that rather than sending their own people on foreign missions, they needed to find locals who would execute critical elements on Israel’s behalf.

While spy agencies have long relied on local agents for tasks that insiders can accomplish best—like unlocking doors, cracking safes and planting bugs—the new agents would do more than assist. And unlike “sleeper” agents that Moscow sent to the West during the Cold War and after, who led deep-cover lives for years awaiting instructions that might never arrive, Israel’s operatives were trained for specific missions, former officials say.

Israel tapped its network in 2018 to help steal Iran’s nuclear archives and spirit them out of the country. Israeli officials said the stash included around 50,000 printed pages and 183 computer disks.

Mossad in 2020 enlisted agents inside Iran to help position a robotic machine gun, hidden in the back of a parked pickup truck, along the commute of Iran’s top nuclear scientist. When remote operators hundreds of miles away shot Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, Israel’s local agents were already far from the scene, according to people familiar with the operation.

This June, Israel’s local operatives destroyed Iranian air defenses and spotted high-value targets before and during the attacks, according to former Israeli intelligence officials familiar with the operation.

“What you have is a sort of extension arm, which gives you the best of both worlds,” said Eyal Tsir Cohen, a former senior Israeli intelligence official. “It allows you to operate at a distance but gives you deniability and gives your agents survivability.”

New covert technologies don’t just empower local agents hiding in plain sight. Israeli intelligence agents last year remotely detonated explosives hidden in pagers and walkie-talkies used by members of Iran-backed militant group Hezbollah across Lebanon, inflicting severe damage on the group and killing at least 12 people. Still, the plot behind sneaking the lethal devices into enemy hands was more of a classic covert operation, carried out by intelligence professionals rather than amateurs, according to people familiar with the project.

Other spy agencies have learned from Israel’s new approach, using digital communications and imaging technology in cellphones and drones to blur the lines between intelligence gathering and covert activities.

“Political leaders are increasingly asking intelligence agencies not only to collect information but also to affect the situation on the ground,” said a European intelligence official. “It’s increasingly important to have a special-forces unit inside your intelligence agency.”

Clandestine action—the stuff of thrillers and Hollywood hits—has traditionally served a less colorful policy purpose, somewhere between diplomacy and war. The motto of the Central Intelligence Agency’s covert operations division, the Special Activities Center, is tertia optio, or third option, neither combat nor negotiation.

Flashing fangs in this way can let one side display its abilities to an adversary—such as the harm it can inflict or how deeply it can penetrate a leadership—using acts that fall short of outright war. Covert actions can actually support diplomacy by showing an enemy that armed conflict would fail and, paradoxically, lead to de-escalation, say practitioners.

“You use a combination of covert activity and airstrikes when you don’t want to send in any ground forces,” said Seth Jones, who previously worked in U.S. Special Operations Command and now runs the defense and security department at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. “They generally are not going to win you a war, but they can be effective in many ways.”

That’s what happened in 2007 after Israel spotted an undisclosed facility in Syria that intelligence analysts believed to house an illicit nuclear program. Israeli leaders opted to destroy it with a secret airstrike that they only acknowledged more than a decade later.

Syria, unable to resume a program it had conducted in violation of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, only said at the time that it had thwarted an Israeli airstrike. It staged no direct retaliation.

No country has applied new technology and Israel’s lessons more actively than Ukraine, which is fighting for its existence and has limited capacity to strike deep inside Russia. Following Moscow’s large-scale invasion in 2022, Kyiv made innovative use of commercially available drones for reconnaissance, targeting and dropping improvised explosives. Ukrainian troops tapped crowdsource intelligence on Russian troop positions, aggregated through software similar to ride-sharing apps.

A turning point in Kyiv’s covert operations came after Russian forces in March 2022 massacred civilians in Bucha, a quiet commuter town outside Kyiv. Ukrainian intelligence officials told their Western counterparts they would replicate Israel’s reprisal for the Munich Olympic murders, according to people in the meeting.

Ukraine intensified purges of holdover Russia sympathizers from its SBU intelligence agency and set out to professionalize on the model of Mossad.

Outgunned by Russia in weaponry, Kyiv ruthlessly exploited its few advantages available for covert action. Its agents proved adept at getting near their targets because most Ukrainians speak Russian and many have Russian passports, relatives or homes, allowing them to blend into Russian society. Rampant corruption in Russia also means that information and access can often be bought.

Ukraine also blurred lines on the battlefield. A Ukrainian intelligence officer with the call sign Paragraf said last year she created a fake account on a Russian dating app using AI-generated photos and connected with Russian soldiers. Sending carefully selected responses generated by ChatGPT, she tempted the soldiers to share photos of themselves. Paragraf’s colleagues then used details in the photos to pinpoint the soldiers’ locations and called in airstrikes.

As war dragged on, SBU agents inside Russia staged increasingly daring attacks, often abetted by Russians unaware of their role. SBU operators assassinated a general in Moscow using a bomb hidden in a scooter and killed a propagandist in St. Petersburg with an exploding statuette presented by an unwitting Russian woman at a public event. The strikes mixed detailed human intelligence with advanced remote technologies that allowed many of Ukraine’s agents to evade capture.

Russia has also employed local agents inside Ukraine and Western Europe. Dutch authorities in September, acting on information from the country’s Military Intelligence and Security Service, arrested three 17-year-old Dutch men for allegedly receiving payment from a hacker group linked to the Russian government. The three received equipment to map and hack Wi-Fi systems at official buildings, potentially “for digital espionage and cyberattacks,” according to the Dutch public prosecutor. A Kremlin spokesman rejected the allegations as groundless.

A big distinction, say intelligence specialists, is that Russia’s local agents generally work for pay, and many don’t know that they are working for Moscow. Israel and Ukraine, in contrast, have developed networks of agents who act out of conviction.

Operation Spiderweb’s Tymofeyev was one of those agents. A dual Ukrainian-Russian citizen, he had worked over recent years in the Russian industrial city of Chelyabinsk, about 900 miles east of Moscow.

Tymofeyev’s wife Kateryna, also a dual citizen, moved to Chelyabinsk with him in 2018. There she ran a tattoo parlor that locals said stayed open late in the evening, Russian state media reported.

The couple’s legitimate public life allowed them to operate so openly that when Tymofeyev last year set up a road-freight business for the operation, he was able to rent a warehouse near the local field office of Russia’s FSB state security service.

Technology allowed Ukraine to run the operation from afar, but it also presented engineering challenges because even digital connections need time to cover distance. The drones would be attacking targets up to 3,000 miles away from their pilots, so video signals would lag slightly, potentially causing image delays known as latency that could botch the strikes. Ukrainian planners carefully constructed software and the communications channels to minimize latency, according to people involved in the work.

Israel took similar measures with the remote machine gun it used to kill Iranian nuclear scientist Fakhrizadeh in 2020, according to a person familiar with the attack.

Ukraine’s high-tech approach in Spiderweb allowed it not just to hit distant targets but to protect its agents. The Tymofeyevs left Russia days before the strikes. Ukrainian officials say the couple is now in a secure location.