By Souad Mekhennet and

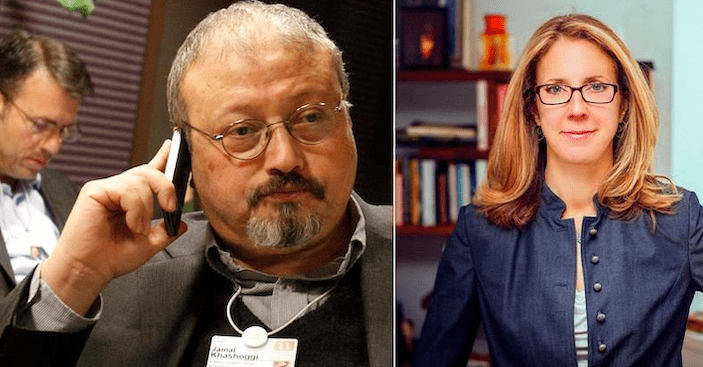

Jamal Khashoggi had been in the United States for only a few months when the forces he had fled in Saudi Arabia made clear that he would never fully escape.

He was at a friend’s home in suburban Virginia in October 2017 when his phone lit up with an incoming call from Riyadh. On the line was Saud al-Qahtani, a feared lieutenant of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The royal heir and his henchman were at that point in the early stages of a brutal crackdown in the kingdom — arresting rivals, torturing enemies and silencing critics. Khashoggi had previously been banned from writing or even tweeting, but fear that worse could be in store had prompted him to seek refuge in the United States.

Qahtani was uncharacteristically amiable on the call. He told Khashoggi that public comments praising Saudi reforms, including a decision to allow women to drive, had pleased the crown prince. He urged Khashoggi to “keep writing and boasting” about Mohammed’s achievements. While the conversation was cordial, the subtext was clear: Khashoggi no longer lived under Saudi rule, but the country’s most powerful royal was monitoring his every word.

Khashoggi reacted with a combination of the nerve and trepidation that would define the remaining months of his life. He challenged Qahtani about the plight of activists he knew had been imprisoned in the kingdom, according to a friend who witnessed the exchange. But even as he did so, the friend said, “I saw how Jamal’s hand was shaking while holding the phone.”

[After journalist vanishes, focus shifts to young prince’s ‘dark’ and bullying side]

A year later, Khashoggi, 59, would be dead, and Mohammed and Qahtani would be implicated by U.S. intelligence agencies in his killing, which was carried out by a team of assassins dispatched from Riyadh.

The crime has roiled relations between the United States and Saudi Arabia, exposed the ruthless side of a crown prince who was supposed to represent the kingdom’s enlightened future, and revealed the extent to which the Trump administration prioritizes protecting an oil-rich ally over humanitarian concerns.

The case has also taken on the dimensions of a global cause. Khashoggi, a contributing columnist for The Washington Post, was a writer of modest influence beyond the Middle East when he was alive. In death, he has become a symbol of a broader struggle for human rights, as well as a chilling example of the savagery with which autocratic regimes silence voices of dissent.

Khashoggi’s life and work, particularly in his final year, were inevitably more complicated than can be captured in that idealized frame. The complete truth about his fate remains elusive in large measure because of a determined Saudi effort to obscure events — an effort that included relaying false information to executives at The Post in the days after Khashoggi’s death.

This account of his final 18 months, which reveals new details about Khashoggi’s interactions with Saudi officials, his activities over the last year of his life as an exile and his killing, is based on interviews with dozens of associates, friends and officials from countries including Saudi Arabia and the United States as well as Turkey, where Khashoggi was killed and dismembered inside the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul on Oct. 2.

Underestimating the Saudis

Khashoggi was an advocate for reform in his country, but he neither saw himself as a dissident nor believed in bringing radical change to a nation that has operated for the past eight decades as an absolute monarchy.

He relished his newfound freedoms in the United States and the attention his writing got from a Western audience, but he often resisted appeals from associates to be more forceful in his criticism of the kingdom. He was by many accounts depressed by the separation from his country and the strain that his departure and work placed on his family.

Even in exile, Khashoggi remained loyal to Saudi Arabia and reluctant to sever ties to the royal court. In September 2017, at the same time he was embarking on a new role as opinion columnist for The Washington Post, he was pursuing up to $2 million in funding from the Saudi government for a think tank that he proposed to run in Washington, according to documents reviewed by the paper that appear to be part of a proposal he submitted to the Saudi ministry of information.

Khashoggi also sent messages to the Saudi ambassador to the United States, Khaled bin Salman — the brother of the crown prince — expressing his loyalty to the kingdom and reporting on some of his activities in the United States, according to copies reviewed by The Post.

In one case, Khashoggi told the ambassador that he had been contacted by a former FBI agent working on behalf of families of victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks — in which 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi. He said he would go forward with the meeting and emphasize “the innocence of my country and its leadership.”

But in the conspiracy-driven climate of Middle East politics, Khashoggi came under mounting suspicion because of his writing as well as associations he cultivated over many years with perceived enemies of Riyadh.

[Crown prince is ‘chief of the tribe’ in a cowed House of Saud]

Among Khashoggi’s friends in the United States were individuals with real or imagined affiliations with the Islamist group the Muslim Brotherhood, and an Islamic advocacy organization, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, regarded warily for its support of the public uprisings of the Arab Spring. Khashoggi cultivated ties with senior officials in the Turkish government, also viewed with deep distrust by the rulers in Saudi Arabia.

After leaving the kingdom, Khashoggi sought to secure funding and support for an assortment of ideas that probably would have riled Middle East monarchs, including plans to create an organization that would publicly rank Arab nations each year by how they performed against basic metrics of freedom and democracy.

Perhaps most problematic for Khashoggi were his connections to an organization funded by Saudi Arabia’s regional nemesis, Qatar. Text messages between Khashoggi and an executive at Qatar Foundation International show that the executive, Maggie Mitchell Salem, at times shaped the columns he submitted to The Washington Post, proposing topics, drafting material and prodding him to take a harder line against the Saudi government. Khashoggi also appears to have relied on a researcher and translator affiliated with the organization, which promotes Arabic-language education in the United States.

Editors at The Post’s opinion section, which is separate from the newsroom, said they were unaware of these arrangements, or his effort to secure Saudi funding for a think tank. “The proof of Jamal’s independence is in his journalism,” Fred Hiatt, editorial page editor of The Post, said in a statement. “Jamal had every opportunity to curry favor and to make life more comfortable for himself, but he chose exile and — as anyone reading his work can see — could not be tempted or corrupted.”

A former U.S. diplomat who had known Khashoggi since 2002, Salem said that any assistance she provided Khashoggi was from a friend who sought to help him succeed in the United States. She noted that Khashoggi’s English abilities were limited and said that the foundation did not pay Khashoggi nor seek to influence him on behalf of Qatar.

“He and I talked about issues of the day as people who had come together, caring about the same part of the world,” Salem said. “Jamal was never an employee, never a consultant, never anything to [the foundation]. Never.”

It is not clear that the Saudi government knew of Khashoggi’s ties to the Qatar foundation, although the kingdom routinely engages in surveillance of dissidents abroad.

To friends and family members, Khashoggi’s connections were indicative of his intellectual curiosity and disregard for rigid national, religious and ideological boundaries. He traveled constantly, attended dozens of conferences each year and developed long-standing friendships with people whose opinions were at odds with his own.

Nevertheless, Khashoggi knew that his writings and associations carried risks. He told friends and colleagues repeatedly that he would be imprisoned if he ever reentered Saudi Arabia, and he spoke often of his concern for his four children, including a son who remained in the kingdom and had faced intermittent harassment from the authorities there.

In the end, Khashoggi underestimated what Saudi Arabia was capable of as he entered the consulate in Istanbul to collect paperwork needed to remarry and begin rebuilding a personal life that had experienced some turmoil during his exile.

“His biggest fear was being imprisoned but not being killed,” said the friend who witnessed the Qahtani call, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for his own security. “He had never thought of that.”

‘Lord of the Flies’

The October 2017 phone call was part of a long series of interactions between the Saudi columnist and Qahtani, a 40-year-old veteran of the Saudi Air Force who emerged from a decade of maneuvering in the royal court as one of the crown prince’s closest advisers.

Qahtani was given broad authority to protect the image of the crown prince, widely known by his initials, “MBS.” It was an assignment that involved flooding social media platforms with propaganda and using espionage capabilities to monitor critics. At times it also meant banning those perceived as being disloyal — including Khashoggi — from writing or posting comments online. Under Mohammed and Qahtani, many activists have also been imprisoned for their dissent.

With more than a million followers on Twitter, Qahtani is derisively known as “Lord of the Flies,” a reference to the swarms of social media operatives — “electronic flies” — that descend on perceived adversaries of the kingdom and Mohammed.

Even before Mohammed began making his move to claim the title of crown prince, Qahtani was scouring the private sector for tools that could aide him in his efforts of suppression. Emails released by WikiLeaks show that someone using Qahtani’s identity pursued spyware capabilities from an Italian company as early as 2012.

A lawsuit filed last month by a Saudi exile in Canada, Omar Abdulaziz, accused the Saudi government of monitoring his text message exchanges with Khashoggi by using Israeli software designed to secretly control an ordinary smartphone, turning it into a surveillance device against its owner.

Qahtani was working to mute Khashoggi’s voice as early as 2016.

The journalist, a native of Medina, had an eventful but often bumpy career over several decades in Saudi Arabia. Drawn to radical causes in his early years, Khashoggi traveled to Afghanistan in the 1980s as a correspondent where he interviewed Osama bin Laden and posed for a picture holding a military rifle.

Khashoggi was fired twice as editor of Saudi Arabia’s Al-Watan newspaper because he was seen as agitating against the government. But he was also an insider in the royal court. In between those editing stints, Khashoggi worked as an adviser to Prince Turki al-Faisal, the former head of Saudi intelligence, when the prince served as ambassador to the United Kingdom and then the United States.

The first major clash between Qahtani and Khashoggi came in late 2016, when the writer was working as a columnist for the London-based Al-Hayat newspaper. At a time when Mohammed and others were celebrating the election of Donald Trump, who promised a far warmer relationship with Riyadh than President Barack Obama had pursued, Khashoggi was more cautious, warning in mid-November 2016 on Twitter that the Saudis should be wary of the untested American president.

Shortly thereafter, while Khashoggi was attending a conference in Qatar, Qahtani called to inform him that he was “not allowed to tweet, not allowed to write, not allowed to talk,” said a Khashoggi associate who, like others, also spoke on the condition of anonymity for security reasons.

Qahtani added, “You can’t do anything anymore — you’re done.”

Khashoggi’s ban over the ensuing eight months coincided with a period of intense intrigue in Riyadh. As Mohammed maneuvered to consolidate power, his enforcer began building his capabilities, including “tiger teams” tasked with carrying out overseas abductions and the interrogation of prisoners. It was hard to reconcile such operations with the innocuous name of Qahtani’s department: the Center for Studies and Media Affairs.

The power grab

In April 2017, Khashoggi left Saudi Arabia for three weeks to stay in London with a Saudi businessman and fellow former adviser to Prince Turki, Nawaf Obaid, who had had his own falling out with the royal court. The two talked about Khashoggi’s desire to move to the United States, according to a person familiar with their discussions.

But Qahtani surfaced again, calling Khashoggi in London to tell him that all would be forgiven if he returned to Riyadh. It was part of Qahtani’s “hot-cold” handling of Khashoggi, the person said, alternating between being menacing and reassuring.

In June 2017, Mohammed and his supporters carried out an extraordinary power grab, detaining the designated crown prince Mohammed bin Nayef, a 57-year-old grandson of the founding Saudi monarch. He emerged from his detainment to issue a humiliating public pledge of loyalty to his much younger cousin, Mohammed, relinquishing the title of crown prince.

The turbulence added to Khashoggi’s fears. In June, as Mohammed was plotting, Khashoggi made his exit, packing his bags, locking up his house and boarding a flight to Washington.

His departure triggered a further attempt to secure his obedience. This time it came not from Qahtani but the Saudi information minister, who called Khashoggi in August to tell him that the writing ban had been lifted and that the government might be prepared to give him money to set up a pro-Saudi think tank in Washington.

The minister, Awwad Alawwad, the former Saudi ambassador to Germany, also relayed a potentially unsettling request. “The crown prince would like to see you,” the minister said, according to a Khashoggi colleague who overheard the call. Saudi officials deny that the minister mentioned Mohammed.

Always conflicted about his relationship with the royals, Khashoggi explored the think tank offer, and even submitted a proposal, according to documents reviewed by The Post. His plan described an entity that would be called the “Saudi Research Council” in Washington, with an initial budget of $1 million to $2 million.

The proposal outlined ideas such as cultivating relationships with other influential organizations, but it seemed aimed at shoring up the Saudi reputation abroad. It notes, for example, that “an irresponsible media” had unfairly maligned the kingdom over alleged connections to terrorist groups for many years, and that the council could work on behalf of Riyadh “to regain its positive role and image.”

The proposal also outlined a plan to form a team for the purpose of “monitoring potential negative news.” The team would follow emerging story lines and social media “that might explode against the kingdom” then “notify the ministry in Riyadh.”

The prospect of such a Saudi-friendly endeavor appealed to members of Khashoggi’s family who at times faced travel restrictions and other hardships imposed by Riyadh in apparent retaliation for his work. Khashoggi’s eldest son, Salah, a banker in Saudi Arabia, and other family members urged him to pursue the think tank plan.

But Khashoggi was also being prodded by others to reject Riyadh’s entreaties, and it’s not clear that the ministry of information was ever prepared to proceed.

Khashoggi appears to have reached a fateful decision in this period to turn further away from the only country he ever considered home. His marriage subsequently disintegrated and his eldest son cut off contact with him for months, friends and associates said.

Khashoggi’s children declined to be interviewed for this article.

In conversations, Khashoggi seemed alternately despondent and invigorated, proclaiming to one friend: “I am a free man, and I am going to change Saudi Arabia.”

Raising his voice

Khashoggi’s arrival in Washington came at an auspicious time for The Post, which was seeking writers for an online section called Global Opinions. One of its editors, Karen Attiah, reached out to Khashoggi to ask him to write on the forces roiling Saudi Arabia.

On Sept. 18, 2017, Khashoggi’s first column for The Postappeared with a stark opening line: “When I speak of the fear, intimidation, arrests and public shaming of intellectuals and religious leaders who dare to speak their minds, and then I tell you that I’m from Saudi Arabia, are you surprised?”

The column was also a declaration of his own independence. “I have left my home, my family and my job, and I am raising my voice,” he wrote. “I want you to know that Saudi Arabia has not always been as it is now. We Saudis deserve better.”

[Read Jamal Khashoggi’s columns]

To hear such unflinching words from a Saudi writer was rare. The fact that they appeared on such a prominent platform would likely have been unnerving to those around the crown prince.

Mohammed had largely succeeded in Washington at casting himself as a leader who would bring Western-style reforms to Saudi Arabia. He had cultivated such a close relationship with the Trump administration that he routinely traded messages and phone calls with Trump’s son-in-law and adviser, Jared Kushner, outside traditional diplomatic channels.

Khashoggi was now writing for a publication that could undercut the crown prince’s narrative in Washington. It was less than two weeks later that Khashoggi got the call that made his hands tremble.

Khashoggi did at times praise the crown prince, crediting him for reforms, including allowing movie theaters to open in the kingdom. But he also seemed to grow more bold in his criticisms.

In November, Khashoggi compared Mohammed to Russian President Vladimir Putin just as a brutal new crackdown began in the Saudi capital. Hundreds of wealthy Saudis, including members of the royal family, were detained at the Ritz-Carlton hotel, many of them reportedly beaten while being interrogated, accused of corruption and forced to surrender billions of dollars in assets. Khashoggi criticized Saudi Arabia’s policies in Lebanon, its bombing campaign in Yemen, its blockade of Qatar, its repression of women and its opposition to a free press.

Khashoggi was never a staff employee of the Post, and he was paid about $500 per piece for the 20 columns he wrote over the course of the year. He lived in an apartment near Tysons Corner in Fairfax County that he had purchased while working at the Saudi Embassy a decade earlier.

As the months went on, he struggled with bouts of loneliness and stumbled into new relationships. He secretly married an Egyptian woman, Hanan El Atr, in a ceremony in suburban Virginia, though neither filled out paperwork to make it legal, and the relationship quickly fizzled.

Khashoggi pursued other ventures. Among them was a plan to create an organization called Democracy for the Arab World Now. He sought out financial backers and turned for organizational help to Nihad Awad, the head of the Council on American-Islamic Relations. The organization has worked to ensure the fair treatment of Muslims in the United States, but its support for the uprisings of the Arab Spring led Saudi authorities to see it as an adversary.

Khashoggi cultivated friendships with people with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, an organization that he joined when he was a college student in the United States but subsequently backed away from. The organization is banned by autocratic regimes in the Middle East.

Khashoggi also appears to have accepted significant help with his columns. Salem, the executive at the Qatar foundation, reviewed his work in advance and in some instances appears to have proposed language, according to a voluminous collection of messages obtained by The Post.

In early August, Salem prodded Khashoggi to write about Saudi Arabia’s alliances “from DC to Jerusalem to rising right wing parties across Europe…bringing an end to the liberal world order that challenges their abuses at home.”

Khashoggi expressed misgivings about such a strident tone, then asked, “So do you have time to write it?”

“I’ll try,” she replied, although she went on to urge him to “try a draft” himself incorporating sentences that she had sent him by text. A column reflecting their discussion appeared in The Post on Aug. 7. Khashoggi appears to have used some of Salem’s suggestions, though it largely tracks ideas that he expressed in their exchange over the encrypted app WhatsApp.

Other texts in the 200-page trove indicate that Salem’s organization paid a researcher who did work for Khashoggi. The foundation is an offshoot of a larger Qatar-based organization. Khashoggi also relied on a translator who worked at times for the Qatari embassy and the foundation.

Hiatt, The Post’s editorial page editor, said that Khashoggi’s writings show no attempt to favor the Qatar position. “He doesn’t attack Saudi Arabia’s campaign against Qatar, as Qatar might have wanted,” Hiatt said. “Nor does he embrace MBS’s reforms, as the crown prince might have wanted. On the contrary: he courageously stands up for Saudi dissidents — and for the cause of freedom throughout the region — while trying to nudge the reforms in a constructive direction.”

Khashoggi and Salem seemed to understand how his association with a Qatar-funded entity could be perceived, reminding one another to keep the arrangement “discreet.” He voiced concern that his family could be vulnerable.

As she reviewed a draft of the Aug. 7 column, she accused him of pulling punches. “You moved off topic and seem to excuse Riyadh…ITS HIGHLY PROBLEMATIC.” The next day he wrote back that he had submitted the column, saying, “They’re going to hang me when it comes out.”

A syringe

This image taken from CCTV video shows Khashoggi entering the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul on Oct. 2, 2018. (Hurriyet/via AP)

By July 2018, the Saudi crown prince had commanded subordinates to find a way to bring the exiled columnist back to the kingdom, according to intercepted communications examined by U.S. intelligence officials.

They saw an opportunity in late September, when Khashoggi entered the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul seeking paperwork he needed for a marriage to a Turkish woman. He was told to return the following week. Khashoggi said he would be back the following Tuesday.

After attending a weekend conference in London, Khashoggi returned to Istanbul early in the morning on Oct. 2 and called the consulate to say he would be there by 1 p.m. He met his fiancee, Hatice Cengiz, for breakfast and told her of his plan. Concerned about him going alone, she skipped obligations at a university in Istanbul to accompany him. As he left his phones with her and went inside, it was the last time she ever saw him.

Several Saudi teams were already in place, having arrived on a pair of jets from Riyadh. The operatives had met with Qahtani before leaving, according to Saudi officials. Assigned to the team was Maher Mutreb, a Mohammed bodyguard who had worked at the Saudi Embassy in London at the same time as Khashoggi.

What happened inside might never have emerged were it not for listening devices planted in the Saudi Consulate by Turkish intelligence. The recordings span several days and capture operatives discussing in advance of Khashoggi’s arrival their plans to subdue and kill him, according to Western intelligence officials.

Khashoggi seemed to realize quickly that he was in danger. A member of the team asked whether he would take tea, and Khashoggi replied yes with an edge in his voice that made it clear that he sensed that this ritual act of politeness presaged something sinister, according to the officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss classified material.

A member of the team informed Khashoggi that he was going back to Saudi Arabia, according to a Western official who said that for a moment Khashoggi seems to have believed that he was going to be drugged and abducted. The Saudi team, however, brought a syringe packed with enough sedative to be lethal, the officials said.

The rest of the recording suggests there was no intent to take Khashoggi alive, multiple officials said. It captures the writer gasping for air in a physical struggle that gives way to silence. The horror resumes with the sound of an electric motor, presumably a saw that a special member of the team — a crime scene expert from the Saudi Ministry of Interior — used to dismember Khashoggi’s body.

Saudi officials maintain that the team did not bring a saw but used implements found at the consulate, citing the statements that the suspects have given authorities.

Khashoggi’s body has not been recovered. Saudi officials said that the killers entrusted Khashoggi’s remains to an accomplice in Turkey. Turkish authorities said the Saudis have yet to provide any evidence or identify this supposed individual.

Publisher, diplomat meet

Khashoggi’s disappearance, reported to Turkish authorities by Cengiz after she had waited outside the consulate for more than three hours, set off a frantic search for clues in Istanbul and Washington.

At The Post, publisher Fred Ryan appealed for help from senior Trump administration officials at the White House and State Department. Ryan also drafted a letter to Mohammed, delivered via diplomatic channels, the day after Khashoggi disappeared.

Trump officials were responsive during the initial days after the writer’s disappearance. Then, suddenly, the administration’s willingness to engage seemed to evaporate. It was as if Mohammed’s ardent backers understood, perhaps from early intelligence reports, that Khashoggi would not be found alive and that what they faced was no longer a case of a missing journalist but a looming diplomatic crisis.

Ryan’s attempts to get information from the Saudi government were met with denials and falsehoods.

After days of requests, Khaled, the Saudi ambassador and brother of the crown prince, agreed to meet with Ryan at The Post publisher’s Georgetown home. He arrived around 9 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 7, five days after Khashoggi disappeared.

The ambassador indicated that he had been gathering information from Riyadh and that Saudi Arabia did not regard Khashoggi as a threat. “Jamal has always been honest,” he said. “We have never perceived him as being an asset of [a hostile country]or anyone else.”

The ambassador proceed to make a series of assertions that defied logic and were contradicted by details emerging from Istanbul.

Ryan asked about reports that Saudi planes had flown into and out of Istanbul around the time of Khashoggi’s disappearance, pressing the ambassador on the presence of any Saudi aircraft. The ambassador responded categorically, saying that such reports were “baseless” when, in fact, such flights had taken place and the teams had flown back to Saudi Arabia within hours of Khashoggi’s death.

Asked to provide evidence backing up Saudi Arabia’s claims that Khashoggi had departed the consulate safely, the ambassador said that video cameras at the compound “weren’t recording” because of technical problems.

Ryan was incredulous. “You can walk around the block here and you will appear on a dozen video cameras,” he said motioning to the surrounding neighborhood. “I don’t understand this.” Saudi authorities have since concluded that the consulate cameras were intentionally disabled.

Ryan questioned the ambassador about other Saudi claims that seemed riddled with gaping holes of logic. Why would Khashoggi have exited through the consulate back door, as some had suggested, when his fiancee was waiting out front? Why would he deviate from what he had done just days earlier, when he entered and left through the same door?

The ambassador was adamant. Allegations of Saudi involvement were “baseless and ridiculous,” he said, noting that Saudi investigators had already arrived in Istanbul and questioned employees at the consulate. “It’s impossible that this would be covered up and we wouldn’t know about it,” he said.

In a statement Friday, Saud Kabli, the director of communications at the Saudi Embassy, said: “Nothing the Ambassador shared with Mr. Ryan in their conversation was an attempt to mislead. The information provided was the best information we had at that time. Unfortunately, that information has since proved to be false.”

The conversation concluded after an hour. Ryan ended by saying that if Khashoggi were killed or abducted by Saudi Arabia it would be “the most depraved and oppressive act against a journalist in modern history.”

Recalling the meeting in an interview, Ryan said that “overwhelming evidence has emerged indicating that virtually everything they told us was false.”

Saudi Arabia has detained 21 people in connection with Khashoggi’s killing, and removed five senior officials — including Qahtani — from their jobs. Saudi officials have continued to deny that the crown prince was involved. Though the CIA has concluded with medium to high confidence that Mohammed ordered the operation, President Trump has sought to insulate the crown prince, saying “maybe he did, maybe he didn’t.”

Turkish intelligence officials have identified Qahtani as the mastermind and indicated that he was the recipient of a message from a member of the kill team during the operation informing him that the “deed” had been done.

Saudi officials suggested that Qahtani created the crisis by driving Khashoggi from the kingdom, only to see him gain a more prominent platform for his criticism abroad. Qahtani then hatched the plot to silence Khashoggi in an effort to avoid the wrath of the crown prince, a theory that has the virtue from the Saudi perspective of shielding the royal heir from blame.

U.S. intelligence agencies tracked a flurry of messages between Mohammed and Qahtani in the hours before and after Khashoggi was killed. The Post was shown purported copies of those messages, texts that centered on mundane matters including a solar energy program and discussion of remarks by a foreign official. It was not possible to establish the authenticity of the documents.

Associates of Khashoggi draw little distinction between the crown prince and his enforcer. “Qahtani has been the source of all evil” for Khashoggi, said a friend of the journalist. “A thug. A liar. A bastard.” But each time Qahtani targeted Khashoggi, the associate said, “it’s understood who is telling him to do it.”

On Oct. 3, one day after Khashoggi’s death, while his fate remained uncertain, his researcher contacted The Post to say that he had a draft of a column that Khashoggi had begun writing before his disappearance. It was published two weeks later.

In it, Khashoggi lamented that “Arab governments have been given free rein to continue silencing the media at an increasing rate,” and that the region was “facing its own version of an Iron Curtain, imposed not by external actors but through domestic forces vying for power.”

“We need to provide a platform for Arab voices,” he said.

Correction: Nihad Awad is head of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, not the Center on American-Islamic Relations. This story has been updated.

Julie Tate and Zakaria Zakaria contributed to this report.

Souad Mekhennet is a correspondent on the national security desk. She is the author of “I Was Told to Come Alone: My Journey Behind the Lines of Jihad,” and she has reported on terrorism for the New York Times, the International Herald Tribune and NPR.

Greg Miller is a national security correspondent for The Washington Post and a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize. He is the author of “The Apprentice,” a book on Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential race and the fallout under the Trump administration.