On April 10, an explosion rocked the Natanz nuclear facility in Iran—the most recent salvo in a long-running shadow war between the Islamic Republic and the forces seeking to prevent it from reaching the military nuclear threshold. Foreign media sources attributed the blast to a covert operation by Israel’s Mossad, but no party has officially taken responsibility, and Washington has explicitly denied playing any role.

The functional damage to Iran’s nuclear program appears to be significant—but Iran’s nuclear ambitions have hit a speed bump, not a brick wall. Its nuclear program has suffered a far less decisive blow than Iraq’s did when Israel struck the Osirak reactor in 1981 or than Syria’s did in 2007. The attack on Natanz, however, promises to affect the nuclear diplomacy now underway between Iran and the United States. How each side interprets the blast will be as critical a factor as the damage to the facility itself. At stake is not just the future of Iran’s nuclear ambitions but the ability of the United States and Israel to contend with them in concert.

URGENCY AND LEVERAGE

When U.S. President Donald Trump came into office in 2017, his administration concluded that the 2015 Iran nuclear deal was deeply flawed and would ultimately facilitate Iran’s becoming a nuclear threshold state by 2030. Washington withdrew from the agreement in 2018 and pursued a policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran’s economy and its leadership, with the expectation that the United States would rejoin the deal and lift sanctions only after the agreement’s loopholes had been closed.

Iran initially held off on retaliating, waiting instead to assess the economic impact of the sanctions. By 2019, sanctions had clearly dealt a devastating blow to Iran’s economy, in particular, the regime’s oil exports. At that point, Tehran adopted a more active strategy in which it sought to impose costs on the United States and its regional allies without provoking a full-blown conflict. Iran gradually escalated its nuclear violations while attacking U.S. forces and Middle Eastern partners through conventional and plausibly deniable means: for instance, Tehran backed Houthi forces in Yemen as they initiated almost daily attacks with advanced missiles and drones against critical infrastructure in Saudi Arabia.

The regional and nuclear tracks of Iranian foreign policy might appear to be separate, but in fact they are part and parcel of a unified strategy. Iran aims to project conventional power in order to protect its nuclear program. Nuclear weapons capability, once achieved, will ensure the regime’s survival, whereupon Iran can use its conventional forces to subvert regional states under the cover of a nuclear umbrella. Despite diverging threat perceptions, Washington and Jerusalem are in agreement on the importance of maximizing the distance between Iran’s regime and a nuclear weapon. Yet they seem to differ over the most effective method for doing so.

Washington would ideally have sought to both return to and improve upon the nuclear deal in a single step, but Tehran’s counterpressure has led the White House to adopt a two-stage approach. Because Tehran has shortened its breakout window since the initiation of Trump’s maximum pressure campaign by breaching the nuclear deal, the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden views a return to compliance with the agreement as an important first step in defusing a potential crisis. Next, Washington aims to build a “stronger and longer” deal through follow-on agreements that close some of the deal’s loopholes by extending sunset clauses, allowing for inspections anytime and anywhere, limiting Iran’s ballistic missile program, compelling Iran to come clean regarding the previous military dimensions of its nuclear program, and further restricting nuclear research and development.

But the White House will likely find that it is not so easy to continue diplomacy after returning to the 2015 agreement. Once the nuclear deal has been reinstated, the United States may lack the necessary economic and political leverage over Iran to negotiate additional pacts. Even now, as the United States and Iran pursue indirect talks about returning to the deal, Tehran is escalating its violations and advancing toward the nuclear threshold, so as to heighten Washington’s sense of urgency and desperation to reinstate the agreement. The sabotage of Iran’s nuclear facilities in Natanz disrupted that dynamic by functionally damaging the program and setting it back considerably.

A SHARED APPROACH

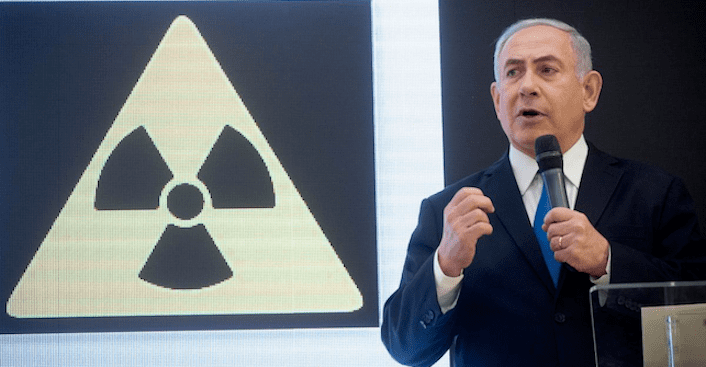

The Iran nuclear issue has been a sore point between the United States and Israel for nearly a decade, despite the very deep and enduring security partnership between the countries and their shared aim of preventing Iran from going nuclear. The United States kept talks with Iran a secret from Israel in 2012, and subsequently Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu took a publicly defiant stance against U.S. President Barack Obama’s Iran policy in 2015. Given this history, the two countries may be inclined to view each other’s diplomatic or covert actions on this issue with suspicion. But the two dimensions could be complementary—rather, they must be, because either without the other will almost certainly fail to prevent Iran from going nuclear over the long term.

It does not take an expert negotiator to understand that whichever party is more desperate for a deal can expect the terms of such an agreement to favor the other party. Israel has no formal role in the negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program and will not be a signatory to a future agreement, but it understands that pushing Iran further from the nuclear threshold will reduce Washington’s haste to return to the deal while Tehran still remains desperate for sanctions relief. Alternatively, in the event that a nuclear deal cannot be reached or revived, Netanyahu would be all too happy to return to the Trump administration’s maximum pressure approach in an effort to turn the Iran nuclear program into a toxic issue for the Iranian leadership by inflicting tremendous economic pain on the country as well as perpetrating numerous humbling incidents of sabotage.

The White House has not yet made clear how it views the latest covert operation against Iran’s nuclear program, but the attack could create friction between the United States and Israel. If the operation was not coordinated in advance on the bilateral level, the Biden administration might look askance on it as an effort to disrupt indirect nuclear talks between the United States and Iran in Vienna. Washington might even hold Israel responsible for Iran’s ensuing decision to increase enrichment to 60 percent.

If Israel intends to continue its covert campaign against Iran’s nuclear program, it ought to do so within the framework of a joint strategy with the United States. Such bilateral cooperation and coordination will enable Israel to set back Iran’s nuclear development while minimizing the risk of escalating tensions vis-à-vis Iran or poisoning its relationship with the United States. The idea that Washington might negotiate with Iran about its nuclear program while greenlighting efforts to degrade that very program may seem absurd—but consider that Iran is doing the exact opposite of that by expanding its program while negotiating. And if Iran continues ratcheting up its nuclear activity during talks, the United States may find that its leverage has evaporated when it feels compelled to reach whatever agreement is on offer to avert a major nuclear crisis.

The framework for such coordination ought to be a U.S.-Israeli agreement to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. The two sides would work to reach an understanding of their common aims and design plans of action to achieve them. This shared approach will prove especially critical in two highly possible scenarios: if negotiations to return to the 2015 deal collapse or if the talks succeed but attempts to reach a stronger and longer agreement stall.

The pact should delineate agreed upon nuclear redlines for Iran, formulas for calculating Tehran’s distance from the bomb, contingency plans for a wide range of possible scenarios, a division of labor in the event of a last resort military option, and joint exercises to ensure that the military option remains credible. The agreement should also include a clause that limits how long the United States will remain a party to the revived nuclear deal while seeking a stronger and longer agreement—perhaps one year or 18 months—after which time Washington would withdraw and reinstate sanctions if no follow-on agreements with Iran are forthcoming.

Focus on the nuclear issue should not allow Iran a free pass in the region. Given that the Islamic Republic’s subversive regional activities cannot realistically be contained through an agreement, the United States and its Middle Eastern allies should instead contest them in a regional constellation that operates simultaneously with the nuclear track. A parallel U.S.-Israeli agreement on the Iran nuclear program may not only be the best bet for preventing Tehran from getting the bomb but also essential to preventing the Iran nuclear issue from becoming radioactive for the relationship between Israel and the United States.