On June 19, 2017, the Islamic State’s Wilaya (Province) of Raqqa, one of the two main cities of the ISIS “caliphate,” released a 36-minute-long Arabic language video, “The Purification of Souls.” The video included many of the elements we have seen repeatedly in ISIS propaganda: images of battle, dead enemy corpses, and calls for attacks in the West, in “the lands of infidelity.”

But coming as Kurdish led-Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) units inexorably bear down on Raqqa, the video also has a remarkable, extended elegiac tone unusual for ISIS propaganda. It is a Ramadan video and so a focus on the eternal and the divine is not out of place, but one has rarely seen so much weeping and emotion in an ISIS video, that is weeping and emotion on the part of ISIS fighters, not of their many victims.

Almost six minutes pass in the video focusing first on death and loss, and then on the sweetness and transitory nature of life: a grave is filled in with dirt; a young man gazes up at the heavens in the midst of Raqqa’s rubble; an old man pulls a battered bicycle out of the ruins of a house; gold coins are counted and spin into eternity; a blacksmith labors wearily at his task; another man treads a path through fallen, sere leaves; a father gazes at his newborn baby; you see images of innocent children, of smiles and of flowers, of gold and of trees. You see normal streets and then those same streets that have been reduced to rubble.

This is Raqqa and it is in a way about the ongoing Coalition air campaign against ISIS. But the commentary is about much more than that. The commentator notes that those who have chosen the path of Jihad in the Path of God have made a better choice than the things of this world, of al-Dunya. You then hear the voice of a dead man, of Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, just as you see an ISIS fighter on a sand berm shot and falling slowly to his death. Al-Zarqawi notes that there is in life, in the end, nothing for the Muslim but jihad and worship of their Lord. Focus, instead of this passing world, on the eternal, on al-Akhira, rather than this life.

The video then shifts to the obligatory battle scenes, of minor skirmishes in the olive groves and unfinished cinder block houses of Raqqa’s outskirts portrayed as if they were the invasion of Normandy. The message here is not just about Raqqa but a much broader point, that patience and steadfastness will, sooner or later, lead to ultimate victory.

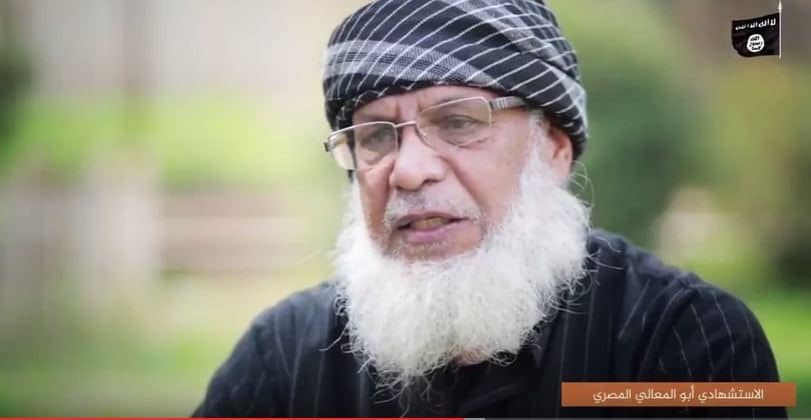

The scene shifts again now from the battlefield to the testimonies of individual ISIS fighters and suicide bombers. Several are young boys and old men. It is clear, as has been the case in other ISIS videos for quite a while, that the organization is seeking to maximize manpower by using the young, the elderly, and even the handicapped or war wounded as it tries to stave off defeat and compensate for its battlefield losses. The tone here is intimate, personal, and emotional, as individuals relate, often with tears, their struggle over doing the right thing in fulfillment of the tenets of their faith and overcoming the distractions and resistance of everyday life. Anyone who sees such testimony would be hard-pressed to say that these are losers or nihilists, or that the motivation for many ISIS fighters is anything but spiritual, emotional, and deeply-held. This is, of course, a propaganda video which presents a skewed and fabricated image of the reality of ISIS. But certainly the motivating force here is lovingly and carefully portrayed as belief and idealism.[i] One young boy relates how he registered to fight and was sent away to come back the next day. He remained convinced of what he wanted to do and told his mother, who was filled with joy.

An older man relates how most of his boys are mujahids and some are martyrs. He says he wishes had 20 sons to contribute to the fight, but has become convinced of himself taking up arms. Another older man tearfully says to remember that you are a guest and a stranger on this earth, and that Allah, for Whom we long, may accept us as martyrs. A smiling young man follows him, reminding viewers that the gates of heaven are open for the martyrs.

And just to make clear what the goal is on this earth for all this sacrifice and martyrdom, still another speaker spells it out. All these explosions and all these suicide operations, these Zarqawiyat, are to utterly extinguish unbelief (Kufr) from the earth so that in the end the worship of Allah alone will exist on the earth.

There is both apparent strength and debility here. One can look at this video and – rightly – see the weakness of an organization scraping the bottom of the barrel, taking boys, old men, office workers, doctors and dentists, and the disabled into its ranks as cannon fodder. But one can also see the inherent power to move men’s minds to action that has mobilized thousands outside the borders of the Islamic State and that continues to inspire acts of mayhem even as the military fortunes of the Islamic State decline.

The irony is that three things are happening now simultaneously in this space for ISIS: (1) the imperative to do more worldwide, more and greater acts of mayhem, is paramount; (2) the ability for ISIS to carry out complex operations is increasingly hindered by its physical decline, as safe havens and established patterns are disrupted; (3) the ideological framework of ISIS, with all its political-religious power, remains, more or less, intact and potent in the same way as the dead Anwar Al-Awlaki and dead Al-Zarqawi still inspire.

And while wars are fought on the battlefield, they are also fought in the mind and in the media. MEMRI recently documented, as it does almost daily, people openly demonstrating their allegiance to the Islamic State on social media.[ii] Some recent ones came from El Salvador and Tokyo, from a Nigerian prison, and from comfortable venues in Poland and Australia. One recent ISIS video from Mosul featured an elderly Egyptian who had previously lived in the U.S. States volunteering for a suicide mission. His last words to the infidels before he drove off to kill them in his SVBIED was a paraphrase of a Hadeeth of Muhammad repeated three times for emphasis: “We are coming to slaughter you.”[iii]

As the Islamic State declines in its Syrian-Iraqi heartland, it will still leave behind a massive material culture. On June 11, 2017, the pro-ISIS Al-Yaqeen Media outlet issued an infographic documenting 41,230 media items produced by ISIS in the past three years. Of those, 2,880 are videos. This does not even include non-official material produced by ISIS supporters, or indoctrination by rival jihadi groups. The ISIS footprint, once it is “gone” from Raqqa and Mosul, will remain massive and will continue to shape and influence for years to come.

The great American conservative Catholic thinker Russell Kirk once wrote: “All great systems, ethical or political, attain their ascendency over the minds of men by virtue of their appeal to the imagination; and when they cease to touch the cords of wonder and mystery and hope, their power is lost, and men look elsewhere for some set of principles by which they may be guided. We live by myth. ‘Myth’ is not falsehood; on the contrary, the great and ancient myths are profoundly true.”[iv]

Obviously, ISIS is not by itself a “great ethical or political system,” but it certainly appropriates from one, from Islamic history and practice, and then selectively chooses various elements for maximum effect, which provides the depth and “appeal to the imagination” that the violence, the surface glitz and the superficial appeals to action by shallow youth alone cannot satisfy. It is all too easy to look at Salafi-jihadism and see only the slaughter and the intolerance. But there is more than that.

So the ISIS brand has, in a way, conquered as it has matured. Today, it is not, as far as we can tell, the latest video or act that radicalizes, but a much broader image which is itself made up of the sum of real actions and pronouncements, and tens of thousands of videos, photos, articles and commentary (including those against ISIS). ISIS is itself part of a much larger – and often bitterly contending and contradictory – brand of Islamist and jihadi action and thought, which has real power because it is rooted in the numinous and because it is also tethered in the language and aura of political revolution.

The unmooring of society happening most dramatically in the Sunni Arab Muslim world which has led to the rise of ISIS is also happening, to a lesser but real extent, in non-Muslim societies, in the West and perhaps in other places, as young people – even in affluent, democratic states – feel alienated from all sort of societal processes, from the political to the spiritual and economic, making them ripe for all sort of simplistic, powerful political pathologies.

In this reading of history, ISIS is not the past but the future. An organization that can couple an arresting political-religious narrative to a plausible reality on the ground may well find shallow, bored, disenchanted youth who are looking for something new and exciting in a perception of certainty coupled with redemptive violence. In such a depiction of the political and spiritual moment, the challenge is not just Salafi-jihadi interpretations of Islam but any sort of convincing, well-articulated “new dogma” which can captivate youth to violence, this could be of the extreme left or far right or some sort of religious or ethnic based nationalist proposition, or a new iteration of the Al-Qa’idism we have seen in the past.[v]

One leader of the evanescent anti-capitalist Occupy Wall Street movement in the U.S. has spoken of the future as a place where “authenticity goes hand in hand with edginess,” and that in this future that he sees being born, “the majority does not follow its center, it undulates towards its inspirational edges.”[vi] While OWS didn’t amount to much in the end, for many young people, ISIS and similar groups do live and breathe “on the edges” and that is where they get their power, in the “edginess” and rigidity found on the blade of a knife.

In a world where polite society and the cultural elite increasingly highlight the hedonistic cult of the individual or the vague feel-good brotherhood of hegemonistic globalism as the only two insipid choices available, many will seek something else, a cause that is about real sacrifice for something important. This will usually not lead to terrorism or even violence and is, in fact, a noble condition, to believe in something sincerely and fight for it.

As horrific and baleful a reality as the Islamic State is, the larger human impetus for sacrifice and faithfulness, expressed by dying or even killing for something important or transcendent, remains and is deeply rooted in the human psyche and imprinted on our spirits. We blind ourselves if we think this is a challenge only to be solved in the battlefields of Raqqa, or in the meeting rooms of Davos or Silicon Valley or Turtle Bay, for that matter.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice-President of MEMRI.

[i] https://www.memri.org/reports/they-are-neither-losers-nihilists-worshipers-death-nor-sick-cowards%E2%80%93-rather-believers-and

[ii] https://www.memri.org/jttm

[iii] https://www.memri.org/jttm/egyptian-isis-fighter-featured-video-says-he-left-us-caliphate

[iv] http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org/2013/06/we-live-by-myth.html

[v] https://www.cfr.org/blog-post/rise-ethnonationalism-and-future-liberal-democracy

[vi] http://www.globatron.org/hashtag/author/micahwhite