After months of nebulous plotting, the domestic and foreign actors who drove opposition to Hamdok’s reformist government will become more discernible as the generals look for ways to solidify their hold on power.

Two-and-a-half years after the fall of dictator Omar al-Bashir, Sudan has witnessed another military coup. The generals struck less than forty-eight hours after a visit by U.S. special envoy Jeffrey Feltman, commencing a power grab that seems to have succeeded for now. Military authorities have arrested cabinet ministers and members of the transitional civilian government, dismissed governors, placed Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok under house arrest, cut internet access, seized state media, and decreed a state of emergency.

In an address to the nation on October 25, coup leader Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan justified his actions and reiterated his commitment to “the constitutional path” and the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement with various rebel groups. On the latter front, he called on the last two rebel holdouts—Abdel Wahid al-Nur of the Darfur-based Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and Abdelaziz al-Hilu of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), based in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan—to fully join the peace process and help usher in “a new Sudan…of freedom, peace and justice.” Burhan, who was previously the country’s de facto head of state before spearheading the coup, sought to portray the military’s action as a “correction” to the transitional process, emphasizing that the revolution was in danger and pledging to appoint a technocratic government that will guide the country to democratic elections in July 2023. Yet the essential question to be decided on the streets of Sudan in the coming days is clear: will the military solidify its rule enough to make and unmake governments for the long term, or will its power decrease in accordance with the framework guiding the post-Bashir democratic transition?

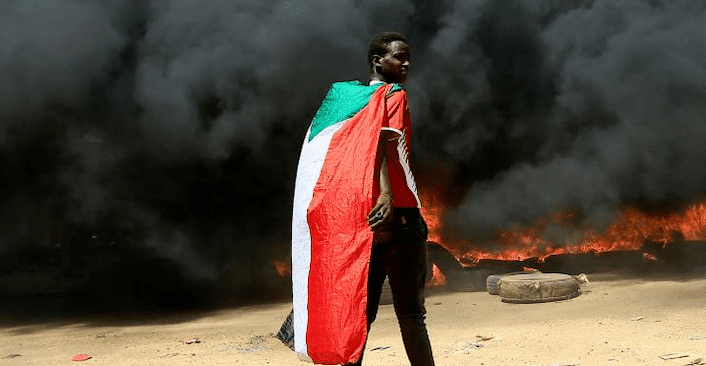

Just last week, Sudan witnessed massive popular demonstrations supporting the civilian government and marking the anniversary of the 1964 uprising, which overthrew the country’s first dictator, Ibrahim Abboud. As news of the current coup circulated, scattered protests broke out with promises of more to come. Mohamed Nagy Alassam—a key leader of the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), which took part in the demonstrations that ousted Bashir’s Islamist regime—called for peaceful opposition to the military’s action. The country’s well-developed civil society movement has proven to be resilient and creative in the face of brutal regime repression in the past, though it now faces its biggest challenge since early 2019.

What Led to the Coup?

The warning lights for Sudan’s fragile transition have been flashing red for some time now. On September 21, the government announced it had foiled a coup attempt by another army general, Abdul Baqi al-Bakrawi, who was supposedly working in sync with pro-Bashir elements. Meanwhile, a series of suspiciously timed and murkily led demonstrations broke out in the coastal region, with notables from the Beja people and other factions praising the military and calling for change in the civilian government while disrupting commerce and port access. Small crowds in Khartoum called for the same thing. The sense of walls closing in and hidden hands moving was palpable.

Further evidence of burgeoning conspiracies emerged on October 19, when Facebook announced that it was disrupting two large social media networks targeting users inside Sudan. One was connected to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by ambitious general Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (aka “Hemeti”), who serves as Burhan’s deputy and is seen as the real strongman of the military faction. The other network was connected to Bashir loyalists and comprised more than a hundred accounts with around 1.8 million followers. Such activity points to a longstanding plot by military elements and Islamist subversives to undermine Hamdok’s reformist government.

Indeed, by ousting the prime minister, the coup plotters removed a respected international civil servant who had made visible progress in reversing Sudan’s isolation after three decades of Islamist dictatorship. The country had finally secured its removal from Washington’s State Sponsors of Terrorism List and taken important steps toward economic reform endorsed by the World Bank and IMF. Hamdok also removed Bashir-era laws against blasphemy and “public order” decrees that regulated how women dress, cover their hair, and travel in public. And last year, he publicly attended the yearly memorial for the late liberal Islamic reformer Mahmoud Muhammad Taha, who was executed for apostasy in 1985 by a previous Islamist regime. These details are important because one of the narratives being promoted by pro-military elements is that the generals intervened to somehow “save” Sudan from pro-Bashir loyalists. Such Islamist loyalists certainly exist, but Hamdok was not one of them.

Policy Implications

Because the coup happened shortly after the U.S. special envoy had seemingly calmed tensions between civilian officials and the military, it constitutes a direct challenge to Washington. The plotters must feel quite emboldened by regional allies, who appear to have convinced them that the fallout is manageable and that their “technocratic civilian government” plan will eventually win over enough of the international community to keep them in power and garner sufficient foreign assistance. To facilitate this outcome, the military or its civilian front men may try to take high-profile diplomatic steps, such as finally sending Bashir to the International Criminal Court in The Hague or openly making peace with Israel (Hamdok’s government was already cautiously exploring both of these paths).

Assuming they weather popular anger, the generals will also need to put together a credible civilian government. This presents them with a dilemma: if governance and economic figures continue to lag or worsen, they will no longer be able to blame the civilians they just overthrew. The junta will be hard-pressed to do better than Hamdok on those issues, and its leaders have little public legitimacy despite their efforts to appropriate the language of Sudan’s youths and revolutionaries.

Consequently, the regional Arab governments and Sudanese politicians who support the new military rule will be unmasked in the coming weeks, and as they are, Washington and other parties need to make clear that there are consequences for supporting a rogue regime. Initial public comments from Cairo, Doha, Abu Dhabi, and Riyadh have been muted. But all of these states will need to balance between their individual agendas for Sudan and their complicated relations with the West.

One thing is certain: Sudan will be inherently unstable if its leaders ignore the stated interests of Western governments and the demonstrators who massed on the streets just a week ago. Twice in the country’s recent political history, concerns about such instability have driven unpopular ruling generals to embrace political Islam as a vehicle for some sort of legitimacy. The current military leadership is divided—Burhan may not be in full control, or may have acted in competition with military rivals, while Hemeti has been maintaining a suspiciously low profile since the coup.

In the immediate term, Hamdok’s ouster sets up an open clash with a U.S. administration that did try to help Sudan—though the Biden team could have done much more and sooner to back up its vocal declarations of support for human rights and democracy. Many in the region now see the administration as precipitously heading for the exit on many fronts, despite its protestations to the contrary.

In any case, the brewing clash will likely follow the model of escalation often practiced by the Bashir regime, of which Burhan and Hemeti were a part before they helped remove it. That is, Khartoum would make some outrageous decision, and the international community would engage it in an effort to make the decision less bad. The usual result was a focus on “process” over actual results, thereby giving the regime vital breathing space time and time again. The Biden administration may face the same potential trap in the next few weeks if the generals dangle the prospect of a substitute civilian puppet government.

Prior to the coup, Sudan’s democratic transition was important not only for Africa, which has seen several military coups in 2021, but also for the Middle East, which has been plagued by disappointing democratic transitions in Algeria, Tunisia, and Iraq and outright disasters in Syria, Lebanon, Libya, and Yemen. In that sense, the crisis for the Sudanese people is also a crisis for American diplomacy. Whatever the Biden administration pushed in Sudan two days before the coup either backfired or, more likely, proved irrelevant to a plot that was already in play while Feltman met with the generals.

Washington’s best course of action now is not to waver, but to openly take a hard and clear line against the rule of Sudanese military strongmen (and their civilian enablers once their identity becomes known). Initial steps in that direction have been taken, with the Biden administration suspending bilateral aid and publicly condemning the military. In addition, the generals need to be quietly warned that things could get worse for them if the situation on the ground deteriorates further. The moral way forward—full defense of Sudan’s 2019 democratic revolution and besieged transition—is also the best one for U.S. policy.

Alberto Fernandez is vice president of the Middle East Media Research Institute and former U.S. chief of mission in Sudan.