The exclusive account of how a small band of federal agents and an outsized corrupt official brought down the sports world’s biggest governing body.

The native New Yorker hardly resembled his image as a statesman of soccer — an infamous bon vivant who made so much money for the game’s international governing body, FIFA, that he was hailed as its virtuoso deal maker. He dined often with sheikhs and heirs at the trendiest restaurants and attended society events with a rotating cast of striking companions. His personal travel blog pictured him with the likes of Bill Clinton and Vladimir Putin and Miss Universe. At 400 pounds, with an unruly white beard and mane, he looked like Santa Claus, talked like a bricklayer and lived like a 1-percenter.

Blazer’s big secret, as he looked down on the Manhattan streets, seems so obvious now: He had embezzled his fortune through kickbacks and bribes. And the people who would uncover the scam were with him today, in his apartment, about to dispatch him to take down FIFA.

THERE HAS NEVER been anything quite like the FBI’s investigation into global soccer, which resulted in a series of high-profile arrests starting in May 2015. But so far, only the barest outline of the case has been made public. Wiretaps and classified debriefings remain under seal, as do the identities of confidential informants and the grand jury proceedings that have left 25 FIFA officials facing criminal charges. U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch has appeared at just two news conferences to discuss the case.

Nonetheless, ESPN has compiled the clearest picture yet of the government’s infiltration of FIFA. Over the past six months, ESPN obtained internal FBI emails, scanned confidential Justice Department documents and interviewed dozens of top-level sources who worked inside FIFA, the U.S. Department of Justice and global law enforcement. What emerges is the inside story of how Blazer helped the FBI penetrate a syndicate that he had in part made massively corrupt.

It isn’t far from Trump Tower to the Rego Park section of Queens, where working-class New Yorkers shoehorn themselves into redbrick apartment buildings and where Blazer, in the 1950s, would rush home from school to work in his father’s stationery store. Later, after he had made his millions, he would reflect on the self-doubt that existed deep inside him. It was almost, friends say, as if he felt he didn’t deserve the heights to which he’d risen.

After earning an accounting degree from NYU, Blazer married his high school sweetheart and joined her family’s business: a button-making factory. By the mid-1970s, he was a suburban New York dad spending his weekends coaching his son, Jason, in soccer. Soon, Blazer became fascinated by the sport’s potential for growth in the U.S. He began as a grassroots volunteer administrator with an eye on making the game his career.

By the early 1980s, Blazer had a regional executive post, which enabled him, at the age of 39 in 1984, to sponsor the United States Soccer Federation’s annual convention, just so he could get face time with its delegates. That same year, he was elected the USSF head of international competition. Breaking with the group’s genteel traditions, Blazer began strong-arming promoters to get the men’s national team more matches. He barreled into meetings so he could sit beside influential men like Robert Kraft, who was working to bring the 1994 World Cup to the U.S. But Blazer’s irascible style ultimately ruffled feathers, and he was out at the USSF.

The aspiring mogul next tried to launch a 10-team soccer league and hoped to capitalize on America’s anticipated entry into the 1990 World Cup in Italy, its first appearance in decades. But according to the online magazine Buzzfeed, the league’s owners ousted him upon learning that he was paying himself more than their entire $50,000 team payrolls. A stint helming a team, the Miami Sharks, ended in another debacle: Executives discovered that Blazer spent their startup capital on luxury hotels and other lavish expenses. He skipped out of town, and by 1990, unchastened, he looked even farther south to revive his career, to Guatemala and one of the six regional bodies that compose FIFA.

Blazer knew all about the Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football, or CONCACAF. He’d attended its meetings when he was with the USSF, and he knew it was a sleepy FIFA subsidiary laden with aging bureaucrats. He also knew it was just the place to make his name, so he schemed to field his own candidate for the confederation’s presidency, Jack Warner, a former Trinidadian schoolteacher who was a rising political star in the Caribbean soccer world. Through Warner, Blazer would secure his own ascent.

Warner’s populism and organizing abilities impressed Blazer, and on a trip to Port of Spain to watch the U.S. team defeat Trinidad and Tobago, Blazer visited Warner’s home to pitch his plan. Blazer told the 46-year-old that he could only go so far in his present job as the head of Trinidad’s soccer federation; he should think about stepping up to run CONCACAF.

With Blazer urging him on, Warner won a landslide victory by pledging to use soccer to enrich the poor and give power to his Caribbean colleagues. But then Warner shocked his supporters by moving the group’s headquarters to Trump Tower in Manhattan — and naming Blazer his second-in-command.

At least initially, it seemed a shrewd move. Blazer saw untapped gold mines in the cities that CONCACAF had ignored. He stayed up night after night developing a tournament he called the Gold Cup, to determine a federation champion. This was an instant hit and helped boost CONCACAF revenues sevenfold in its first year, to $1 million. By 1997, Blazer was making so much money for CONCACAF that Warner rewarded him with a prized perk: a seat that Warner controlled on FIFA’s highest council, its 24-member executive committee, or ExCo.

The council was starved for ideas, and Blazer seemed to have a million of them. When the German company that held FIFA’s marketing rights went belly-up, Blazer forcefully argued that FIFA should manage its own rights rather than go through a middleman. The move established a multibillion-dollar gusher of marketing fees. Blazer also launched the Confederations Cup — a competition that included, among others, FIFA’s six regional governing bodies — and the FIFA Club World Cup, a global tournament.

Suddenly, Blazer was jetting to FIFA headquarters in Zurich so the most powerful men in the game could profit from his advice. And like many of them, he helped himself to the spoils. Using his accounting degree, Blazer sent millions of dollars in CONCACAF revenue through a maze of shell companies to offshore accounts in the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas, where he owned a condo at the Atlantis resort. He also looked the other way as Warner stole millions in FIFA grants that were meant for a sports center he was building in Port of Spain.

It was hard to tell which partner in crime had more hubris, but Blazer lived the larger lifestyle. In addition to occupying the $18,000-a-month Trump Tower property, he charged CONCACAF for a smaller one next door, reportedly for his cats. He also held a standing table at Elaine’s, an Upper East Side restaurant where actors and mobsters mingled with cops and reporters, his driver waiting outside as he entertained dinner dates, some dressed in the lavish gowns he kept in his apartment for just such occasions. (He’d divorced in 1995.) To the tourists vying for tables at Elaine’s, Blazer was clearly somebody. But even regulars were hard-pressed to explain precisely what he did. “We all knew he was the only American in FIFA,” says Anne Beagan, a press officer for the FBI who hung out at Elaine’s. “The big joke was, ‘What’s FIFA?'”

His blog, Travels With Chuck Blazer and Friends, transformed from a collection of family photos to a chronicle of his time with world leaders: Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu and Pope John Paul II. There was a series of shots with Vladimir Putin, whom Blazer met in August 2010 when he traveled to Moscow to inspect the sites that Russia proposed as part of its bid to host the 2018 World Cup. In fact, Blazer liked to tell a story about how he checked into the Ritz-Carlton, across from the Kremlin, and was whisked to a private meeting in the Russian Federation office building. There, Putin himself interrupted the discussion to welcome Blazer: “You look like Karl Marx,” the then-prime minister deadpanned before giving Blazer a high-five. A moment later, Putin turned serious, telling his guest that securing the World Cup was a signature priority. “Let us show the world what Russia is about,” Putin said.

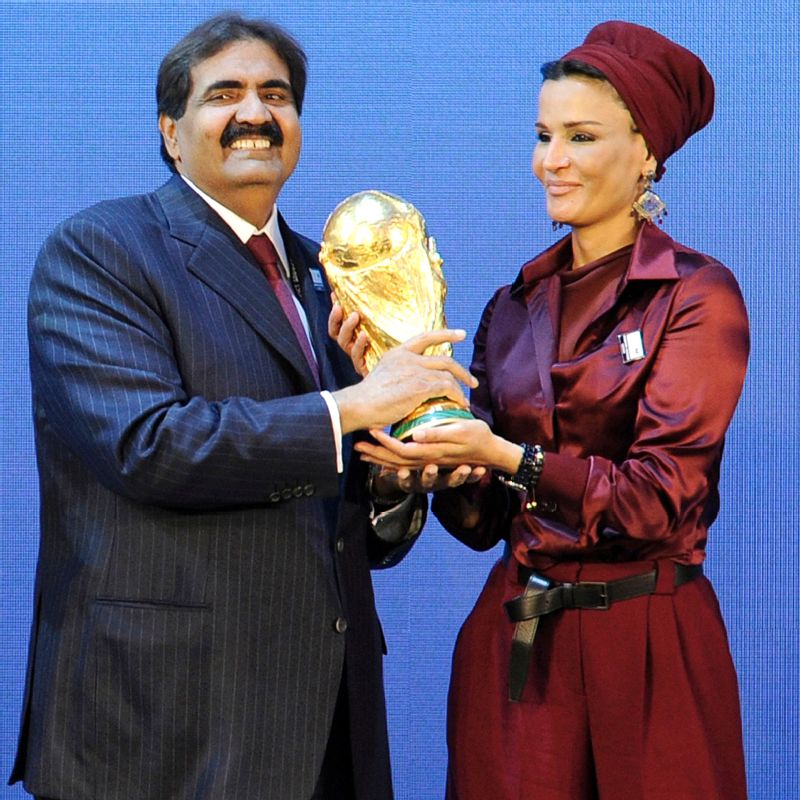

They did. In December 2010, inside the grand hall of FIFA’s headquarters, known as Zurich’s Messe, president Sepp Blatter presided at a ceremony to announce the host countries of the 2018 and 2022 Cups. The hall filled that day with soccer royalty alongside actual kings and princes. Blazer worked the room, shaking hands with, among others, Prince William and David Beckham. The crush of dignitaries was so complete that Bill Clinton, the honorary chairman of the U.S. bid, could get a seat only in the second row, behind Blazer.

Blazer broke out in a satisfied grin when Blatter announced that Russia had won the 2018 Cup. (He had cast his vote for Russia to host the Cup that year.) But he was stunned, along with the other Americans, when Blatter said: “The winner to organize the 2022 FIFA World Cup is … Qatar.”

How could a small nation in which summer temperatures exceeded 120 degrees beat out the United States?

In New York, a team of FBI agents already had suspicions of its own.

IF YOU MENTION football to most feds, the NFL springs to mind. Jared Randall is different. Tall with dark hair and blue eyes, he had played soccer since he was a kid and even attended a 1994 World Cup match in Foxboro Stadium. He went on to captain the team at Division I Manhattan College in the Bronx. After Randall joined the FBI a few years out of school, he even wrangled a spot for himself on the New York City Police Department’s soccer team.

In early 2010, Randall, then 28, was assigned to a specialized group of FBI agents in lower Manhattan. The Eurasian organized crime unit, led by a veteran mob investigator named Michael Gaeta, scrutinized criminal groups from Georgia, Russia and Ukraine that were running sophisticated scams in the U.S. As Randall and Gaeta linked street-level criminal operators to figures in Eastern Europe’s business and political elite, they started piecing together a string of rumors that led them to an unsettling conclusion: Russia might be bribing its way to host the 2018 World Cup.

When he had so many skeletons in his closet … Did he think the stuff wouldn’t come out? Probably not.”

When he had so many skeletons in his closet … Did he think the stuff wouldn’t come out? Probably not.”

– John Collins, a CONCACAF lawyer, about Chuck Blazer

Publicly, FIFA is a registered charity in Switzerland and portrays itself as a prosperous, benevolent organization designed to enrich the many impoverished communities it serves. It had earned $631 million since 2007, according to its 2010 annual report, and vowed to invest $800 million in development projects between 2011 and 2014. Beneath the surface, however, Randall and his colleagues saw something else. Even the laziest ExCo members lived like kings. They each received $200,000 annual stipends, along with liberal per diems every time they went to Zurich. And they controlled the votes that decided where the most watched event in sports, the World Cup, would be played. This selection process seemed engineered for bribery, the FBI agents thought.

Randall and Gaeta began looking into the six regional confederations that administer FIFA’s 207 member nations. The more they looked, the more they found a system of bribery and embezzlement in which billions of dollars in broadcasting, marketing and other fees made a global journey into the pockets of a privileged FIFA few. Soon, alleged Russian payoffs to ExCo members seemed the least of it.

Pursuing a fraud investigation into a worldwide organization like FIFA, however, would be complicated. “It had the potential to be expensive,” says an FBI source who spoke to ESPN on the condition of anonymity. “Given the breadth and time likely to be involved, it was a big ask.”

Fortunately, New York City is big enough for two U.S. attorney’s offices. The Southern District, located a few blocks from the FBI’s Manhattan office, prosecuted high-profile cases. But the Eastern District, located across the East River in Brooklyn, had high volume. As many in New York’s criminal justice system put it, Southern was the show horse, Eastern the workhorse.

Because of this, prosecutors in the Eastern District had a chip on their shoulders. No one was more eager to raise the profile of his office than the head of the organized crime wing, John Buretta. The prosecutor had previously developed a close relationship with FBI agents, helping them obtain high-profile mob convictions. When senior FBI officials in Manhattan sent their FIFA file across the East River for consideration, Buretta wasted little time in taking it on. “It felt like an organized crime case,” says a source close to the case. “It fit with what we did.”

Shortly after Blatter’s World Cup announcement, Buretta officially opened the government’s case against FIFA. The FBI zeroed in on its prime target: the large-living American, Chuck Blazer.

Emir of the State of Qatar Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani and his wife hold the World Cup trophy after the official announcement that Qatar will host the 2022 World Cup. Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images

THE FBI CASE caught a break from a Qatari billionaire. In the spring of 2011, Mohamed bin Hammam, a mannered construction baron and FIFA’s vice president, announced his candidacy for FIFA’s presidency, hoping to stop Blatter from winning a fifth term.

The road to bin Hammam’s election ran through the Caribbean, where Jack Warner controlled 31 delegates, or 15 percent of the total FIFA votes. Three weeks before the election, Warner invited bin Hammam to a luncheon in Trinidad to address leaders from the Caribbean Football Union. When the talk finished, Warner directed delegates to a nearby room. There they each found a brown envelope containing $40,000 in cash, which investigators would later claim bin Hammam had brought on his private plane, part of the billionaire’s slush fund to buy votes.

Blazer was in Miami on CONCACAF business when he learned that day of the apparently brazen bribery occurring in Trinidad. He hit the roof. Blazer’s partnership with Warner had strained. Warner, who started his days at 5 a.m., despised the way Blazer sauntered into the office at noon after being out until the early morning at strip clubs. Blazer, in turn, resented the way Warner spent all his time playing politics in Trinidad.

One of the first calls Blazer made was to FIFA secretary general Jerome Valcke. At nearly 3 a.m. in Zurich, Valcke, a polished Frenchman, listened drowsily as Blazer railed against Warner, calling him “arrogant” and “stupid” for exceeding the kind of corruption that everyone accepted, attempting something so obvious as a naked bribe.

According to two sources who were told about the call, Valcke agreed with Blazer that the incident could do untold damage to FIFA if it went public. John Collins, a Chicago lawyer who represented CONCACAF, remembers getting a call from Blazer shortly thereafter. “You need to look into this,” Blazer told him.

The report that Collins delivered to FIFA eight days later led bin Hammam to drop out of the president’s race; he was ultimately banned from soccer. The report also destroyed the corrupt partnership that Warner and Blazer had built.

Warner was forced to resign his post after a video leaked that showed him appearing to endorse bribery. “If you are pious, open a church, friends,” he was secretly filmed telling his delegates in Trinidad the day after bin Hammam’s visit. “But the fact is that our business is our business.” In the clip’s aftermath, a furious Warner spilled the secrets he and Blazer had kept for two decades: He accused Blazer of regularly embezzling licensing and marketing money.

The whole episode was strange. Taking down Warner so publicly was “such a risk” for Blazer, Collins says, “when he had so many of his own skeletons in his closet. Did he think that stuff from long ago wouldn’t come out? Probably not.”

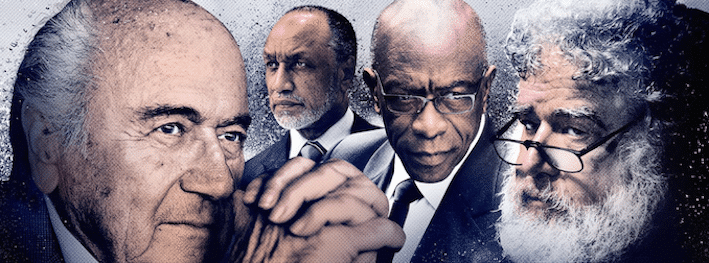

Blazer (right) welcomes FIFA President Joseph Blatter (center) and FIFA Vice President Jack Warner (left) to the CONCACAF Congress in 2009. Imago/Zuma Press

IN RESPONSE TO Warner’s accusations, FIFA opened an ethics investigation into Blazer, which dragged on through the summer of 2011, and through the 11th edition of the Gold Cup. Blazer’s brainchild had come a long way: The Gold Cup debuted that year at Cowboys Stadium, with 80,000 fans turning out to see Costa Rica dominate Cuba 5-0. Over the next three weeks, 13 stadiums planned to host matches involving a dozen countries, culminating with a finale at the Rose Bowl. The tournament would generate $23 million in ticket revenue, over 60 percent more than it had earned just two years earlier.

Unfortunately for Blazer, the good times didn’t last. Chris Eaton, a former Interpol director who had recently taken over as FIFA’s head of security, received word that a group of match fixers had entered the U.S. intent on rigging the Gold Cup. When Eaton looked into the betting patterns of the Cuba-Costa Rica game, along with two others, he drew the troubling conclusion that the matches might have been fixed. While the tournament was still underway, Eaton gave an interview to the German magazine Der Spiegel, in which he announced that Interpol, FIFA and CONCACAF were investigating the suspect games.

Blazer was flabbergasted when he read the article. Why hadn’t Eaton come to him first? Determined to find out whether the allegations were true, Blazer called the one friend he thought might be able to help.

You have no right to question my honor and integrity!”

You have no right to question my honor and integrity!”

– former FIFA president Sepp Blatter to Swiss investigators while being questioned about an alleged payoff

“It was the first time Chuck had ever reached out to me professionally,” says Beagan, the FBI press officer who was part of his Elaine’s crowd in New York. Since the Gold Cup was scheduled to conclude at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Beagan contacted the FBI’s LA office on Blazer’s behalf.

Shortly after that call, Mike Gaeta, the head of the New York squad investigating FIFA, stopped by Beagan’s desk. Gaeta had never shown up unannounced before. Beagan couldn’t imagine the impetus for his visit, until Gaeta told her he knew she was friendly with Blazer. “You should stay away from him,” he said. As Beagan recalled in an interview with ESPN, “I’d been around long enough to understand what that meant. And I didn’t speak to Chuck after that.”

Jared Randall took things from there, reaching out to Blazer himself. ESPN obtained an email the FBI agent wrote on June 13, 2011, in which he told a colleague: “I recently was able to meet with Mr. Blazer … regarding CONCACAF’s recent concerns.”

It was a remarkable twist. Blazer had no idea that he was speaking with the very investigator who had already identified him as a key suspect in the growing probe into the world’s largest sport.

Not long after that meeting, Chris Eaton and two of his FIFA aides arrived at the FBI office in lower Manhattan, ostensibly to share information about match fixing on U.S. soil. Eaton had been in his role at FIFA for less than a year and, as he says, “I could see that FIFA was dirty. It was filthy.”

Eaton handed Randall an assessment that he had compiled on every FIFA confederation and ExCo member, believing it could serve as a scorecard for the agents. On the way out, he turned to Randall and said he thought Blazer was the weak link, given the FIFA inquiry about him.

“He’s got to be ripe now to cooperate, given all the allegations against him,” Eaton said.

A computer image of the “Al Garafa” stadium to be built in Doha, Qatar, for the 2022 World Cup Balkis Press/ABACAUSA.COM/Polaris

BY THE SUMMER of 2011, Randall and Gaeta were confident they could handle the case on their own. But another agent was eager to join the effort, a veteran of the Internal Revenue Service named Steve Berryman.

Raised for a period in England, Berryman was a soccer fanatic who still called the game “football.” He also worked in a branch of the IRS’s criminal division, in Orange County, California, which specialized in combating foreign corruption. In August 2011, Berryman read an article in the U.K. newspaper The Independent, which uncovered the FBI’s interest in Blazer. More than anything, Berryman wanted in.

Berryman took the unorthodox step of phoning Randall. His call was so unusual, in fact, that Randall and his boss, Gaeta, invited the IRS agent to their Manhattan office out of curiosity. According to one source familiar with the series of events, Berryman performed a “dog and pony show” in which he pitched the FBI agents on his specialty — tracking money across borders and through the international financial system. By the time Berryman flew back to LA, the FBI and IRS had formed an alliance that energized the investigation.

Berryman scoured Blazer’s accounts at Citibank, Bank of America, Barclays and Merrill Lynch for evidence of the embezzlement Warner had alleged. Because Blazer hadn’t filed taxes since 2005, it was hard to determine how much he earned. Berryman got to work analyzing illicit payments Blazer had received over the years from shell accounts in the Caribbean and elsewhere.

Berryman discovered a $200,000 wire, dated March 1999, from an account held by a Uruguayan shell company to a Barclays Bank account that Blazer controlled in the Cayman Islands. Another wire to Blazer, this one for $600,000, originated from an account controlled by a Panamanian group. Berryman also discovered that Blazer had skimmed millions that FIFA had earmarked for other purposes. As Berryman tracked additional wires and deposits — many of which would later be revealed as bribes for World Cup votes or kickbacks for Gold Cup marketing and TV rights — he began to fill out the mosaic of Blazer’s activities.

By the time Berryman was finished, it was clear that Blazer had embezzled much of the $20 million he had banked as general secretary over two decades.

While Berryman worked the numbers, Randall traveled through Latin America so often developing leads that he missed a close friend’s wedding. By late 2011, Berryman, Gaeta and Randall paused to assess their progress. They had tracked numerous apparently fraudulent wires and deposits into Blazer’s U.S. accounts. They had identified foreign accounts that Blazer had shielded from the IRS. And they knew that Blazer had failed to pay income taxes for an extended period, giving the agents considerable leverage. But still, they’d gone as far as they could go.

“There comes a point in every investigation when you have to make something happen,” says an FBI source close to the case. “You have to make a calculated decision to do something. At a certain stage, you have to be proactive.”

Attorney General Loretta Lynch speaks during a news conference at the Justice Department in Washington in December 2015. Jose Luis Magana/AP Images

NOVEMBER 30, 2011, was a bittersweet day for Blazer. It was a few days before the anniversary of the death of his friend, Elaine Kaufman. Along with other Elaine’s regulars, he gathered in an Upper West Side auditorium to reminisce about the restaurant owner’s life. Those who hadn’t seen Blazer in a while noticed that he looked unwell. His eyes were puffy, his skin pale, and he’d bloated up so much that he was using a motorized scooter that he often needed to get around. Coronary artery disease and Type 2 diabetes were taking their toll, as was the stress of his secrets.

Accountants working for CONCACAF’s board had scoured his office in Trump Tower that summer, disclosing his finances. In October, board members gathered in a closed-door session and ousted Blazer as CONCACAF’s general secretary.

By November 2011, all that Blazer had left was his position on FIFA’s ExCo. And thanks to the pending ethics inquiry, even that was in jeopardy. Returning home from Elaine Kaufman’s memorial, he was met by two men waiting in the atrium of Trump Tower.

Randall and Berryman hadn’t made an appointment. They didn’t want one. They quickly proceeded to have what an FBI source described as a “come to Jesus talk” with Blazer. They laid out what they had discovered: the shell companies, Blazer’s failure to pay taxes. According to one of the sources close to the case, Blazer folded immediately. In the days following, prosecutors from the Eastern District drew up a cooperation deal that stipulated his role as an informant, and Blazer readily signed it.

According to court documents obtained by ESPN, Blazer would meet with the government 19 times between Dec. 11, 2011, and Nov. 13, 2013. And while the content of these meetings remains confidential, the agents were determined to use what was left of Blazer’s access within FIFA’s ExCo to record his conversations.

All of this led to the moment in Trump Tower when Blazer stood in his apartment in an adult diaper as Randall and Gaeta affixed a listening device to his body. This scene would repeat itself in coming months, though Blazer didn’t exactly ease into his new role as snitch. On early assignments wearing the wire, he came off stilted and suspicious. During a trip to Zurich, for instance, he called Chris Eaton to suggest a friendly meeting at FIFA headquarters. Eaton found the invitation odd; the two men had never met. As Eaton recalls, “He was asking me strange questions. He wanted me to say something, and it wasn’t clear what he wanted me to say.” Figuring something was amiss, Eaton quickly made his exit.

In the FBI, a lengthy organized crime case lasts 12, maybe 18 months. As Randall and Gaeta followed leads through a second full year, colleagues asked them why they were wasting their time, especially since European cops hadn’t been able to crack FIFA in decades. Fortunately, the agents had an advocate in Loretta Lynch, a corporate lawyer and former drug prosecutor who was on her second tour as U.S. attorney for the Eastern District.

“Loretta Lynch was the one who said, ‘Go get it,'” the source says. “She was the one to speak with higher-ups in DC when that needed to happen.”

WHEN THE SUMMER Olympics opened in London, in July 2012, Blazer at last hit his stride. Olympic soccer is a FIFA-sanctioned event, which meant London was another boondoggle for the ExCo brass. Since the considerable FIFA delegation was staying at London’s May Fair hotel, the five-star property was one-stop shopping for the FBI. The agents trained Blazer to use a key chain, as first reported by the New York Daily News, that was loaded with a recording device. All he had to do was toss it onto a table during his conversations.

The list of Blazer’s targets, according to federal documents, included Alexey Sorokin, the head of the Russian bid for 2018, and Frank Lowy, the head of Australia’s failed bid for 2022 — two insiders with knowledge of the bid process.

As the Olympic Games wore on for Blazer, the stress of secretly recording many of his FIFA colleagues began to show. After one especially long day, he found himself sitting at the May Fair bar with an old friend, a Sri Lankan ExCo member named Manilal Fernando.

Recalls Fernando: “I remember how Chuck sighed as we walked in. He said, ‘Thank god there’s no FIFA people here.’ He sounded almost defeated. I had never heard him that down. He wasn’t even looking at me as he was saying it. He was just staring down at his glass of wine and glancing around all the time to make sure nobody was within earshot.”

Fernando says he “knew something wasn’t right,” but he didn’t expect to hear what Blazer had to say next.

“I’m gonna blow this thing wide open,” Blazer told his ExCo colleague. “I’m gonna get the bastards.”

THE DETAILS OF Blazer’s cooperation with the FBI remain hidden behind a wall of prosecutorial secrecy. What is clear: He worked with them for over a year after the London Olympics, and his recordings allowed the Feds to expand their target list. “He was a wealth of information,” says a source close to the case.

Just after 10 a.m. on Nov. 25, 2013, in the federal courthouse in Brooklyn, U.S. District Judge Raymond J. Dearie ordered his courtroom locked for a secret proceeding. Randall and Berryman were behind the closed doors, as was Blazer, who slouched in a wheelchair beside the defendant’s table.

Looking down from the bench, Dearie asked Blazer about his well-being. “I have rectal cancer,” Blazer said, according to unsealed court transcripts. “I am being treated. I have gone through 20 weeks of chemotherapy, and I am looking pretty good for that. I am now in the process of radiation, and the prognosis is good.”

After wishing Blazer luck, Dearie read the charges against him: racketeering, money laundering, tax evasion and the violation of several financial reporting laws. It was a 10-count indictment. In total, Dearie explained, the charges carried a maximum term of 100 years in prison. Blazer pleaded guilty, and Dearie set his bond at $10 million.

Blazer then went on to detail his crimes: “I agreed with other persons in or around 1992 to facilitate the acceptance of a bribe in conjunction with the selection of the host nation for the 1998 World Cup,” he said. “Beginning in or around 2004 and continuing through 2011, I and others on the FIFA executive committee agreed to accept bribes in conjunction with the selection of South Africa as the host nation for the 2010 World Cup.”

Randall had been investigating FIFA for three years, and his efforts had at last been validated: One of the most powerful men in soccer admitted in federal court what no one else had been able to prove. FIFA’s leaders sold their power.

Federal agent Jared Randall (right) confiscates a computer taken from CONCACAF headquarters in Miami. Wilfredo Lee/AP Images

ON MAY 27, 2015, Loretta Lynch — in her new role as U.S. attorney general — announced the indictment of 14 defendants, mostly foreign nationals, in the FIFA case that Blazer had opened up.

Around the same time, and with little fanfare, Swiss police, working with U.S. federal agents, arrived at FIFA headquarters serving a search warrant. Over the next eight hours, they riffled through files and carted out documents relating to the 2018 and 2022 World Cup bids. By week’s end, Sepp Blatter announced his resignation but later hinted that he would stay on through the end of the year and maybe never leave at all.

An air of crisis hung over FIFA’s headquarters through the fall, when a senior official in the Swiss office of the attorney general received a call from a man who identified himself as a “Blatter insider.” The two met on a bench in a Zurich park, where the official learned what only a handful of people knew: Blatter had wired over $2 million in FIFA funds to the head of Europe’s soccer federation, Michel Platini, in 2011. This was the year when Platini, a potential FIFA presidential rival, made the decision not to run for the office.

The new tip led the Swiss authorities to return to FIFA headquarters with a second search warrant, this time looking for a smoking gun: a bank slip reflecting the alleged payoff. In his office, during an interview with law enforcement, Blatter calmly defended Platini’s payment. Eventually, though, his cool reserve cracked. “You have no right to question my honor and integrity!” Blatter shouted.

Later that day, the Swiss attorney general’s office opened criminal proceedings against the FIFA president. On Dec. 3, Lynch revealed 16 new indictments (but none against Blatter).

Even as the Feb. 26 election for a new FIFA president approached, Blatter remained defiant. On Dec. 21, FIFA’s ethics committee banned him from soccer for eight years. The following day, he addressed the media with a large bandage on his right cheek — he had recently undergone mole-removal surgery — looking and sounding like a wounded, disturbed leader. “I am still the president,” he said. “Even if I am suspended, I am still the president.”

Today Jared Randall still tracks international leads. As he recently told a colleague, “I could spend my entire career on this one case.”

A source close to Blazer’s family tells ESPN that these days he is bedridden in a hospital room in northern New Jersey. With a tube down his throat, the FBI’s most important witness is now unable to speak, communicating by keyboard alone. This past November, Dearie postponed Blazer’s sentencing. Prosecutors say they may still need him to testify.