The Balfour Declaration wasn’t like a bolt out of the blue. It wasn’t by some miraculous Jewish power, nor Jewish capital. To understand it, we must look at the wider historical background.

It was the end of World War I. Those days were characterized primarily by the dissolution of empires and the regrowth of the national idea. And at the end of every imperial era, the result is another wave of national liberation. The dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, created new nation states. Borders were moved.

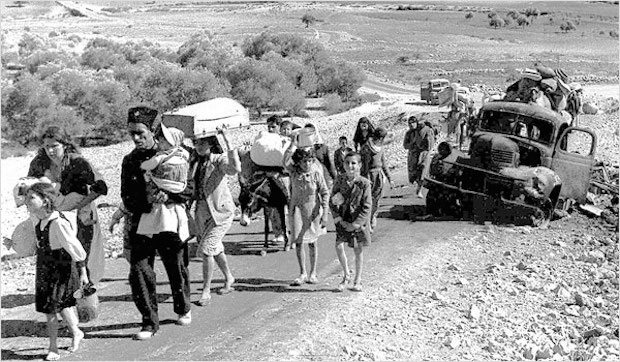

The national liberation, almost every national liberation, exacted a heavy toll. Populations were relocated, usually forcibly, to give the idea of national liberation some substance.

It didn’t end there. The dissolution of the Soviet Union also led to the establishment of a series of nation states. The dissolution of Yugoslavia, a multinational state, led to the establishment of seven national entities—as well as to wide-scale ethnic cleansings.

Several months before the Balfour Declaration, French Foreign Ministry official Jules Cambon sent a letter to Zionist leader Nahum Sokolow, stating that “it would be a deed of justice and of reparation to assist, by the protection of the Allied Powers, in the renaissance of the Jewish nationality in that Land from which the people of Israel were exiled so many centuries ago.” Britain had coordinated with France and the United States before making the declaration.

Two months after the Balfour Declaration, US President Woodrow Wilson issued his Fourteen Points, which were linked by the right to self-determination. In other worlds, recognizing the right of each community that had been under imperial rule to independence, freedom and sovereignty. The idea of national liberation and of a nation state is an anti-imperial idea. It’s true that in the current era, the post-national and anti-national voices are echoing again, even in little Israel, but these voices appear to suffer from a weak historical memory.

Zionism was a national movement, one of many, which jumped on the bandwagon of the same idea, just like the top representatives of the Arab world sought sovereignty and independence based on the same idea. Unlike other people, who were a national minority under a give territory, the Jews were a national minority under many states and empires.

There was one moment in history, immediately after the Balfour Declaration, when the Jewish nationality and Arab nationality even shared joint interests. This was reflected in the Faisal–Weizmann Agreement, which was signed in 1919. In an article published just a few days ago, Prof. Efraim Karsh elaborates on the Arab and Muslim acceptance of the Balfour Declaration and the Jewish nationality idea. Even Talaat Pasha, one of the rulers of the declining Ottoman Empire, which turned into the Turkish nation state, expressed support for the Jewish right to a national home in Palestine.

The main argument presented by the Balfour Declaration opponents is that it ignores the national aspirations of the area’s residents. That’s inaccurate. First of all, the Balfour Declaration itself forbids causing them any harm. Second, their national aspirations were honored as part of the Arab state which the Arab leaders those days, including Emir Faisal, wanted to establish on most parts of the Middle East.

Five years after the Balfour Declaration, after it had already been adopted by the League of Nations, another decision was made, to establish another entity—Transjordan—on lands governed by the British mandate that were allotted to the Jewish state.

Another partition took place in 1947, and the western side of the Jordan River was divided between the Jewish Yishuv and Palestine’s Arab residents. Their national right was honored. It was implemented in all neighboring states. This recognition applied also to those who later became Palestinian.

But the Arab world itself prevented the implementation of this right. The lands were in its possession. There was no occupation. Yet no Palestinian state was created from 1949 to 1967. So the claim that Palestine’s residents were ignored is groundless.

It’s true that there was a Nakba. Palestinians fled and were expelled. It happened in almost every national conflict, and it happened to the Palestinians also because of the Arab rejection of any compromise, especially the Partition Plan.

The claims of injustice suffered by Palestine’s Arab residents because of the Balfour Declaration should be looked into on the background of the reality and norms in the first half of the 20th century. Hundreds of millions of people have gained national liberation and independence, and tens of millions experienced some kind of “Nakba,” including the Jewish Nakba of Jews in Arab countries. The historical context shouldn’t prevent a solution to the conflict. On the contrary, it will put the conflict in its real place.